Chef Vikas Khanna: Feed, pray, love in a pandemic

Khanna has opened a sit-down restaurant at a posh Dubai resort to restart the meter for the pandemic-hit F&B industry

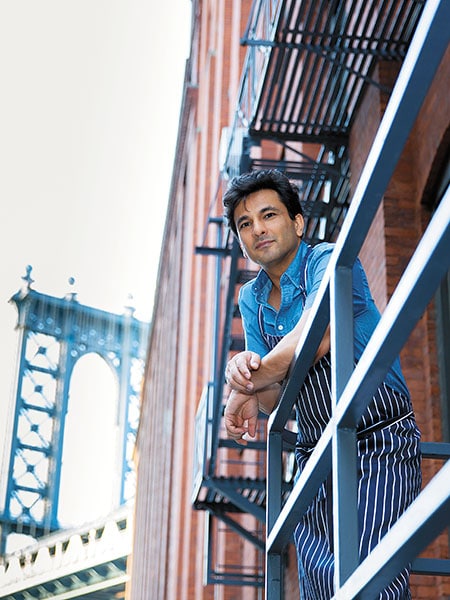

Chef Vikas Khanna at his test kitchen in Brooklyn, New York. From his Manhattan apartment, where he has been confined since March 29, Khanna has collaborated remotely for the opening of a new restaurant in Dubai

Chef Vikas Khanna at his test kitchen in Brooklyn, New York. From his Manhattan apartment, where he has been confined since March 29, Khanna has collaborated remotely for the opening of a new restaurant in DubaiPhoto Courtesy: Team Chef Vikas Khanna

It’s 1 am in New York when we catch up with Vikas Khanna over a phone call. Are you sure this is a good time to talk, we ask. “Why, do I sound sleepy?” he shoots back. He doesn’t. And he isn’t going to sleep anytime soon, he tells us.

Sprawled in front of him are layouts of a movie Khanna has completed with Shabana Azmi—it is in post-production, and likely to be released next year. Once those are vetted, he will start shooting photos for his upcoming cookbook. “I have to click six more images, but looks like I’ll be able to complete only three tonight,” he says. Interspersed are calls with India’s National Disaster Response Force (NDRF), a government agency he is collaborating with to feed the pandemic-hit in the country. “With so much going on, I have no fixed sleeping hours. I keep taking short naps through the day,” he adds.

If his day wasn’t chock-a-block enough, Khanna, 48, opened a new restaurant in Dubai on August 14, with a big, bold, contrarian call of launching a sit-down eatery at a time when the F&B industry is scraping the bottom of the barrel to survive. The months-long lockdown has eroded cash reserves for restaurants that operate on razor-thin margins, and distancing norms post-opening have forced them to reduce covers and footfalls.

The Federation of Associations in Indian Tourism and Hospitality (FAITH), an apex body of tourism and hospitality entities in India, has estimated the sector is at risk of losing ₹15 lakh crore in the wake of the Covid-19 shutdown. Multiple restaurants have downed shutters at Delhi’s Khan Market, among the poshest and most expensive retail spaces in India. In the midst of such an industry-wide crisis, Khanna, in collaboration with JA Resorts and Hotels (with which he also launched Kinara, in Dubai, last September), has opened the doors of Ellora, a casual-dining, seasonal menu restaurant, at a posh resort by the Jabel Ali beach.

The interiors of Ellora in Dubai set up in keeping with norms of social distancing

The interiors of Ellora in Dubai set up in keeping with norms of social distancingImage: Ellora By Vikas Khanna At Ja Beach Hotel; Ja The Resort

But the odds aren’t giving the Michelin-starred chef sleepless nights. “The only way to get the economy back on track is to open projects and create opportunities. If people like us don’t do that, how will the staff take care of their families? It’s okay to talk about staying positive, but I thought the most powerful statement I could make at a time like this was to open a restaurant,” says Khanna, who has also appeared in multiple TV shows, including Masterchef India.

While the name Ellora—chosen by Khanna himself—is meant to represent a beacon of positivity in challenging times, the opening had to navigate multiple roadblocks wrought by the pandemic. The restaurant had to cut down its indoor seating from 80 to 56, food trials had to take place at home kitchens and, most significantly, for the first time, Khanna’s vision had to be executed remotely, with him operating out of his apartment in Manhattan, New York, since March 29. A few runaway successes from Kinara’s menu were borrowed, but most took shape via video calls beginning 8.30 pm Dubai time.

Tandoori pineapple at Ellora

Tandoori pineapple at ElloraImage: Ellora By Vikas Khanna At Ja Beach Hotel; Ja The Resort

Says Ashish Kumar, executive chef, Ellora: “I’ve worked with Khanna on Kinara, so I had an idea about the kind of taste profile he looks for, and worked on that. That apart, we had a buzzing WhatsApp group constantly sharing photos, thoughts, concepts that eventually shaped the menu.” Once the basic dish came together, Kumar moved to the professional kitchen for final tastings with a panel from JA Resorts & Hotels, including the general manager and the director. It led to multiple iterations—like a watermelon curry that had to be refined quite a few times—before a dish made it to the final menu.

Khanna doesn’t know when he will eventually land up at Ellora, but from 11,000 km afar he has fashioned its philosophy to align with the Covid-normal. “In times like these, casual dining works better than fine dining, which is cost-intensive and needs a lot of labour. The idea is to make the chain more efficient and less staff-oriented; it means much more mise en place,” he says. While a typical Vikas Khanna dish would need three counters to assemble, at Ellora he makes do with one and a half. “I have insisted that everything has to be done a la minute, which helps the kitchen run on less staff.” Besides, the pressure on the tandoor, which works on an overload in the kitchens of Indian restaurants, has been distributed among ovens and tawas. “However, and here comes the curse of my Michelin star, I have to meet certain expectations with my dish. My dishes can’t be ‘normal’. That will signify loss of creativity and imagination.”

“Vikas is a born artist,” says mother Bindu Khanna. “He’s never cooked anything simple. That he was different was evident from the creative essays he would write in school. He would never score good marks, but his thoughts were out-of-the-box.” Khanna’s casual-Michelin saffron and almond sheermal, therefore, is prepared with stencilled rolling pins that give it imprints; it’s a climb-down from an earlier sheermal that came with a layer and a surprise filling, but is still fancy enough to border on food art. A prawn ghee roast has podi masala sprinkled with a custom-made mould to resemble peacocks reflecting Indian heritage as well as those that roam the JA Beach Hotel, while menaskai is served with an engraved net of pineapple reduction on top. “At his restaurants, you’re not eating food—you feel like you’re eating paintings,” adds Bindu, who lit the first stove at Kinara and at every other business her son has ever launched.

Kele ke bhaji at Ellora

Kele ke bhaji at ElloraImage: Ellora By Vikas Khanna At Ja Beach Hotel; Ja The Resort

“Yes we’ve had to reduce the number of tables, and I can’t say confidently that we’ll recover our investments. But we have to create jobs, and if the food is good, I believe we’ll never have an empty table. We can’t escape the fact that our diners need new concepts. That’s how the meter starts again,” says Khanna.

“Opening a restaurant right now is a brave thing to do, but Khanna has obviously made some calculations that you and I haven’t. He’s a household name in Dubai and even non-Indians have seen him in Masterchef,” says Vir Sanghvi, columnist and TV presenter. “When I met him for the first time, he had a Michelin star. Chef Atul Kochhar had described him as a young Rajesh Khanna due to his popular appeal. But what struck me was his humility—he never once pretended to be anything but the boy from Amritsar. Yet, beneath that modesty is a tremendous self-belief. He has a strong drive to do what he wants to and he’s a perfectionist.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Tandoori lemon prawn at Ellora

Tandoori lemon prawn at Ellora Along with the NDRF, Khanna has distributed 27 million meals across the country

Along with the NDRF, Khanna has distributed 27 million meals across the country