Indian Pharma's Second Life

Not long ago, innovator pharma companies considered Indian generic drug makers parasites. And then they had a change of heart

It was late evening in August 2008, Arjun Handa, then 28, vaguely recollects. He got a call from a senior executive from pharmaceutical major Pfizer’s Global Established Business Unit in New York, asking if he would like to meet up with their head. Handa’s first reaction was one of disbelief. Early into the conversation, he told the caller he was not interested in selling his family firm Claris Lifesciences. Shortly afterwards, Handa found that Pfizer’s business head David Simmons wanted to talk strategy — something Handa was fond of talking about.

A few weeks later, Handa met with Simmons in Ahmedabad and began visiting their offices in the US. Six months after Handa agreed to the terms in Singapore, he signed up with Pfizer to supply them drugs in May 2009. Handa says, “It was an opportunity [that] we were only talking [about] and no one seemed to be listening. And then it happened one fine day.”

Three years ago, this would have been unthinkable. Global pharmaceutical giants like New York-based Pfizer and Paris-headquartered Sanofi-Aventis, considered Indian drug firms parasites. Companies like Hyderabad-based Aurobindo Pharma and Ahmedabad-based Torrent, made copies of the costly-to-research patented medicines of the innovator firms and sold them cheap locally. These firms also fought court battles against the giant firms to disprove their patents.

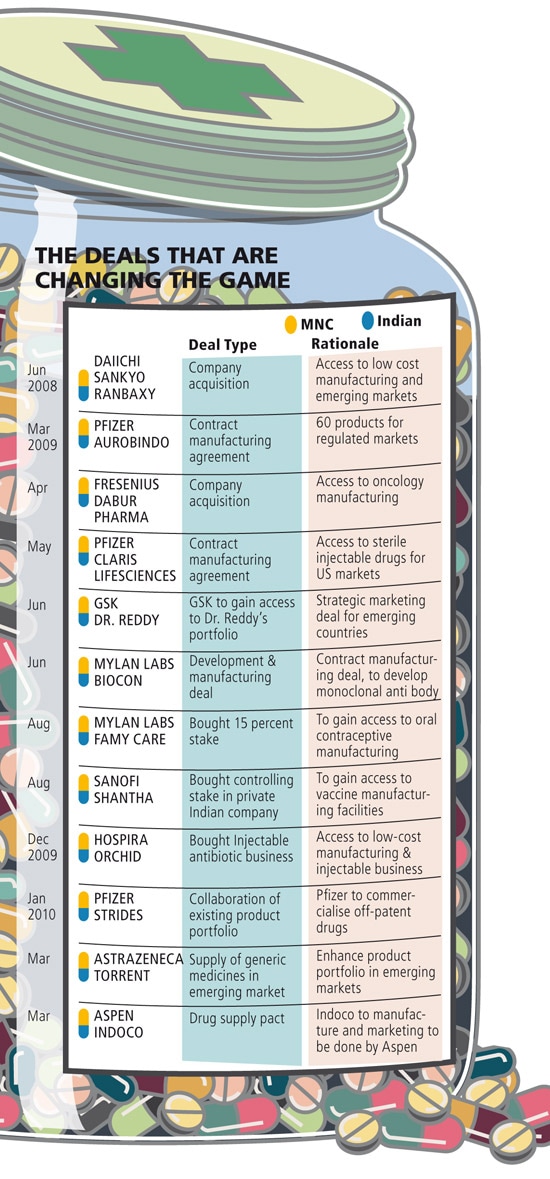

The tide is now changing and how! In the last two years, the very firms who abhorred the Indian drug companies have inked around a dozen deals with them. Japanese firm Dai-ichi Sankyo set off the trend buying off India’s biggest pharmaceutical company, Delhi-based Ranbaxy Laboratories, in 2008. And now, big pharma companies will help Indian firms in distributing copies of international blockbusters medicines worldwide.

The trend is significant for two reasons. Until now, a clear line demarcated the local firms and their overseas counterparts — the Indian firms sold cheap copies, while the MNCs hawked high quality originals. In the new scenario where aggressive firms like Pfizer and UK-based Astrazeneca are looking for deeper associations with local firms, the line has begun to blur. So the fortunes of the Indian firms will now entwine with the MNCs, which was not the case so far.

Second, the long term survival of medium- and small-sized drug firms seemed unsure as they did not have the financial might to set up an international marketing set-up like the big drug firms Ranbaxy, Dr. Reddy’s and Sun Pharmaceuticals. It looked as if Torrent and Aurobindo had missed the plot, as their balance sheet sizes did not give them room to invest big amounts in research and marketing.

Before the recent run on its stock, Torrent’s market capitalisation was $500 million, a tenth of Sun Pharma’s, though both the companies were of similar size in the late eighties. The opportunity to licence their drugs to multinational firms, to sell in regulated markets like the US and Europe and in emerging markets excluding India gives them a new revenue source.