Classroom India: Pearson's New Venture

British publisher Pearson is taking some risky bets in one of the world's biggest education markets. The results could yield the template for a global footprint

In about three months from now, Bangalore will become the first city in the world where Pearson will have a school under its own brand name. Pearson plans to have at least 100 schools in three years. The closest it comes to this model is in Brazil, where it supplies everything that a school needs.

It is a crucial big step for a company that has in the last decade, under the leadership of CEO Marjorie Scardino, reinvented itself as a learning company (it owns brands like Financial Times and Penguin). Education now brings in 74 percent of its revenues and 81 percent of its profits. But Scardino can sense that the learning business is undergoing a massive change. Students are shunning textbooks in favour of Wikipedia and YouTube, and the largest number of school going children are in countries like Brazil, China and India where, till last year, Pearson did not have a big presence.

Scardino knows that unless Pearson, which gets 60 percent of its revenue from North America and relies largely on selling to institutions like schools and colleges, responds to these challenges quickly and aggressively, it will lose its dominant position. Which is why over the last six years, she has been pushing Pearson outside its comfort zone, into newer geographies and businesses in learning, spending $800 million in acquisitions last year. The bulk of this investment went to emerging markets and in businesses that sell directly to consumers. In China, Pearson acquired brick-and-mortar English language teaching schools; in South Africa, it has acquired a majority stake in a company that runs higher education colleges.

In India, that strategy is taking Pearson into the promising but extremely hard territory of running and managing schools and setting up vocational training centres. Like the one in Dadar, Mumbai, where, in a gleaming air conditioned 1,500 sq. ft. training centre, 90 men and women sit in four classrooms, get trained on how to speak English, be better salesmen, work behind the retail counter. In two months, and after paying Rs. 2,000, they hope to be placed in companies like DHL and Costa Coffee, earning Rs. 9,000 a month.

It’s a tough task. No company in India has managed to make good money in the vocational training business. The school business too is highly fragmented. Only two institutions in the last 50 years, DPS and Ryan, have managed to grow their franchise to 100 schools each. A number of factors — scarcity of land inside cities, government regulations and shortage of trained teachers — have made it extremely difficult to scale this business.

If Pearson manages to crack these businesses in India, not only will it emerge as a formidable player locally, but it would also have found a model that it can replicate in other emerging countries. “It is in some sense a laboratory for us to learn about new education systems. We will experiment with new models which we can take to other parts of the world like say South Africa,” says John Makinson, chairman, Pearson India and the man entrusted with the task of growing Pearson’s business in India.

The First Steps

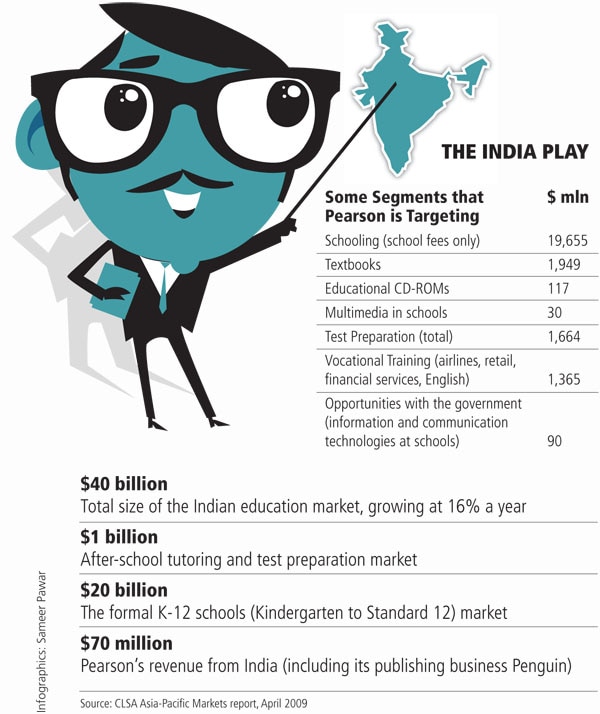

In 2010, revenues from the education business in emerging markets crossed $800 million, growing three times since 2006. But in India, which has the largest number of school going children in the world, its presence was miniscule. According to a CLSA Asia-Pacific Markets report published in April 2009, the Indian education market was worth $40 billion in 2008. Last year, Pearson’s revenue from India (including its publishing business Penguin) was just about $70 million.

Knowing how important emerging markets were to Pearson’s future, in May 2008 Scardino invited C.K. Prahalad, an authority on emerging markets, to join the Pearson board as an independent director. Over the next several months, Scardino and Makinson along with Prahalad and independent board member Patrick Cescau (who, as the ex CEO of Unilever, had firsthand experience of emerging markets like India) had many conversations on what was the best strategy.

It was clear to Makinson that what had worked for Pearson elsewhere wouldn’t work in India. For instance, the school textbook market, Pearson’s bread and butter business, is highly competitive and extremely low priced in India with books selling for Rs. 20-30 a piece. Pearson sells Philip Kotler’s Marketing Management for $55 (about Rs. 2,500) in the US; in India it retails for Rs. 595. In other businesses where Pearson was strong (like computer-based examinations and certification), the market was tightly controlled by the government. But India had businesses that are absent in most parts of the world — for instance a $1 billion after-school tutoring and test preparation market. The biggest money though was in the formal K-12 schools (Kindergarten to Standard 12), estimated at around $20 billion.

While a lot of the strategy was decided at the board level, Makinson needed someone at the ground who understood India and was also steeped in the Pearson culture. Makinson turned to Khozem Merchant. Educated in the UK, Merchant is half Indian and was serving as the India correspondent for Financial Times for the last six years. The choice was unconventional (Merchant has never run a business before) but not unusual for Pearson. Makinson himself was a journalist at Financial Times many years ago.

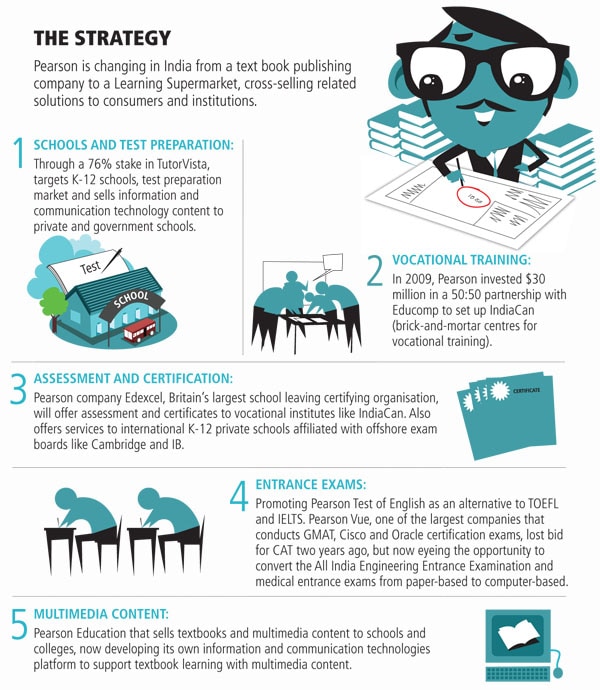

Makinson, who sits on the board of Pearson plc and is the head of its publishing business Penguin, had enough experience of India to know that growing a business organically in India would take him a long time. While Pearson had good products and services, it didn’t understand the local milieu and also lacked the distribution muscle to cover a country as diverse as India. In June 2009, Makinson made two investments in two entrepreneurs who according to him had the firepower and had built businesses of scale in this field. Pearson picked a 17 percent stake in TutorVista, a Bangalore-based company that was offering online tuitions, selling information and communication technology content to private and government schools and managing 20 schools.

The same day Makinson also announced a 50-50 JV with Educomp for setting up a vocational training business, IndiaCan. “There was a sense of urgency to get on the belt quickly and a partnership with proven individuals is a good way of crunching that timeline,” says Merchant.

The Gameplan

Pearson’s biggest investment in India is in TutorVista. It owns a 76 percent stake for $130 million.

For now, Pearson’s investments in the school business are being routed through TutorVista which follows an asset light model of managing a school. While the school (and the land) belongs to a trust, TutorVista manages the operations, which means it controls all aspects of running a school — admissions, curriculum, lesson plans, recruiting and training teachers. The trust and TutorVista split the revenue. The 20 schools that TutorVista currently manages are run under the Manipal brand name, with which TutorVista had a strategic tie up prior to the acquisition. Although the company has the right to use the Manipal name for five years, the new schools being signed up — like the one in Bangalore — will be run as Pearson schools.

Pearson won’t disclose any specifics but CFO Raghav Puri says the company is talking to school owners and investment bankers to acquire more schools around the country.

“As an investor, my views on the education business are mixed,” says K.P. Balaraj of Westbridge Capital that was TutorVista’s first investor. “The best known schools in the country are run by individuals and trusts that are not looking for capital,” he says. While there is a shortage of good schools, there is also a great deal of resistance from parents in sending children to new schools. That means that the leaders are still the older schools — DPS in Delhi and Bishop Cotton in Bangalore.

While in the short term private schools are on Pearson’s radar, there is a bigger opportunity in setting up schools under the public-private partnership model with the government. Meena Ganesh, CFO and MD, Edurite (part of TutorVista), says that there are proposals from the government in Rajasthan where it wants to set up new schools under management contracts with private players. Similar discussions have been initiated with the government of Maharashtra too. It is still early days and there is no clear model in sight but when the tenders are floated, TutorVista will make a play for it. It is also one of the reasons why Pearson was keen to acquire TutorVista.

Strategic Partnerships

Makinson is aware that a lot of the products that Pearson sells around the world are designed for high-price markets in the West. But he says they have made investments in India to re-engineer the products to bring the prices closer to the Indian market. For one of its largest businesses, Dorling Kindersley, the company has set up a centre in Noida where 250 people work to adapt textbooks into digital format that can then be sold around the world. A new product for classrooms, where Pearson will sell digital content along with its textbooks, is based on a platform it sells in the UK, but the content is adapted locally so that Pearson will be able to offer it for Rs. 300 per child to schools.

Infographic: Sameer Pawar

Cost and distribution are the reasons why Makinson says that for its vocational training business IndiaCan, it tied up with Educomp. Today, IndiaCan has 290 centres where it claims to have trained 45,000 students so far.

Pearson is bullish on the vocational training business. “Everywhere I went, I heard the same grumbles, that there were just not enough well-trained people to hire,” says Merchant. For instance, he says, ICICI takes in 35,000 people a year and then spends a lot of resources in training them.

Because vocational training is an unregulated business, it gives Pearson an opportunity to learn how to run a B2C model, and offers a great fit with Pearson’s other businesses. Pearson has two large billion-dollar businesses of testing and certification (awarding). For example, if IndiaCan is training a nurse, Pearson can test what she has learnt, award her a certificate and develop her professionally if she is found lacking. Measuring the training and measuring the efficacy of training is a critical part of this process. “Training in isolation is a useless function because of the competitiveness of the labour market in India. How do I say that one nurse is better than the other?” says Merchant. All IndiaCan centres use the services of a Pearson group company, Edexcel, which is one of the largest certifying bodies in the world.

Will the Strategy Work?

The reality is that no company in India has yet found a way to build a profitable large-scale business in vocational training.

The economics of this business are difficult to manage. Says a competitor, “Unlike preparing a student for IIT entrance where I can charge Rs. 20,000, here the average ticket size is Rs. 2,000-Rs. 3,000, whereas the customer acquisition cost is Rs. 500. If I franchise my operation, I have to give him 60 percent of my revenue. Can you imagine how many people I have to train to make this venture profitable?”

It is still early to say how Pearson will do in India, but people who are in the business for a long time say that it is a difficult industry. Ashish Rajpal, a Harvard-trained educationist and MD of iDiscoveri, says education is caught in the same bind that grips microfinance, where the need to build profitable growth clashes with the social imperative of providing affordable education. On top of it, a vast majority of administrators are simply unwilling to try out new things. “The biggest lie in this sector is that institutions want to improve quality,” he says.

Two years ago, Pearson lost a closely fought order to computerise the CAT exam to another competitor Prometric. While industry observers say it was because Prometric’s bid was more competitive, Pearson says the infrastructure to conduct a mass scale exam simply wasn’t there.

Pearson had advised IIMs to make a gradual two-year change from a paper-based exam to a computer-based one and this was the reason it lost the order. Even though the Indian managers felt that they could have pulled it off in the first year, Pearson plc wasn’t ready to take any chances — what if the operation had botched up? As is now well known, the CAT that year ran into a lot of problems, as a result of which several other exam bodies, the All India Engineering Entrance Examination and other medical entrance exams pushed back their decision to move to computer-based testing by a few years.

It is just the kind of environment global companies find difficult to deal with. Things here move slowly and in a chaotic manner. But for now, Pearson is putting on a brave front and says it has come prepared with a long-term horizon to India. “We are a learning company and know that learning takes patience and time,” says Merchant.

(Additional reporting by Samar Srivastava & Prince Mathews Thomas)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)