Budget 2018: Prudence or populism?

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley will be walking a tightrope as the government is expected to offer relief to the middle class and rural economies, while managing fiscal deficit and boosting investments

Arun Jaitley arrives to present Budget 2017. While last year’s budget came just months after demonetisation, this year’s is the first in the post-GST era

Arun Jaitley arrives to present Budget 2017. While last year’s budget came just months after demonetisation, this year’s is the first in the post-GST eraImage: Sonu Mehta / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Politics and economics are the two focus areas that any government continuously juggles with, especially since veering towards one often means sidelining the other. Ensuring a fine balance between the two isn’t the easiest job, even in the best of times. And these definitely aren’t the best of times.

Recent political and economic developments—including the election results in Gujarat, and conflicting macroeconomic indicators, such as Gross Domestic Product and manufacturing indices—highlight the Herculean task ahead for Minister of Finance Arun Jaitley, as he gears up to present the Union Budget for 2018-19 on February 1.

The Gujarat election results ensured that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) would form the government for the sixth consecutive term in the state. The victory, which followed a pitched battle with a somewhat resurgent Opposition led by the Congress, however, threw up crucial trends that could shape the contours of Budget 2018. The BJP won the election by a narrower margin than in 2012, and it became clear that a sizeable chunk of the rural and agrarian population voted against the incumbent government. The reason, as analysts later dissected, was attributed to distress in the farm economy.

With elections in key BJP-ruled states such as Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh due in 2018, followed by the next general elections in 2019, the rural economy is widely expected to be in focus in the Budget. It is almost certain that Budget 2018, which could well be the last full budget from the NDA-led government before the next general elections, will be a populist one. But the extent to which Jaitley can “balance populism with prudence” will decide its success, says Harsh Goenka, chairman, RPG Enterprises.

Suvodeep Rakshit, senior economist at Kotak Institutional Equities, expects the Budget to be more nuanced in its populism when compared to the pre-election budgets of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government. “UPA’s pre-election budgets were characterised by measures such as hiking the minimum support price (MSP) for farmers’ produce, and other subsidies,” he says. “But the present government is likely to be more subtle in the manner in which it transfers wealth and creates jobs in rural areas. This may be through increased allocation under the MGNREGA (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act) for jobs involving the creation of rural infrastructure, and budgetary support for irrigation facilities, rural roads, bridges and housing.” The overall allocation for rural development could be 20-25 percent higher than last year, adds Rakshit; in Budget 2017, this figure was ₹1.87 lakh crore.

Anindito Mukherjee / Reuters

Harsh Mariwala, chairman of consumer goods maker Marico, is also hopeful that the government will not use doles to stimulate the rural economy and create jobs. “They should boost the rural economy through investments in improving productivity, supply chain linkages, and irrigation; not by hiking MSP,” he says.

“The Budget will also focus on rural housing as this segment has a multiplier effect. It spurs demand for housing material and construction, and also boosts consumption,” says Ajit Ranade, president and chief economist at Aditya Birla Group. “I expect the government to announce schemes through which there will be more income in the hands of the farmers.” He didn’t rule out the possibility of the government increasing MSP to help small farmers.

“I believe the Budget should focus on attracting investments, greater productivity and job creation,” says Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, chairperson and managing director of Biocon. “Measures for the agricultural sector need to be balanced with incentives for corporate India.”

Industry leaders and analysts agree that direct financial assistance (such as increased MSP) to the farm sector, while politically enticing, may not be the best option, given India’s fiscal deficit. Although the government’s efforts to maintain fiscal prudence and stick to its articulated fiscal deficit target has been commendable, economists agree that there may still be a marginal slippage.

Jaitley has previously articulated the government’s commitment to reduce fiscal deficit to 3.24 percent of GDP by the end of FY18, and to 3 percent by the end of FY19. Ranade and Rakshit expect the fiscal deficit for FY18 to be around 3.5 percent, given that the government’s revenue (both tax and non-tax) has been below expectations, owing to falling tax collection under heads like GST, as well as lower-than-expected dividends from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). All of this means the government has very little elbow room to dole out largesse to its electoral constituents, mainly the farm sector and India’s middle class.

There are other factors to consider as well. The full impact of demonetisation, implemented in November 2016, was felt in 2017. As liquidity dried up in the system, it led to obvious challenges for individual citizens, while trade channels found it difficult to continue normal operations. However, as the BJP’s victory in the March 2017 Uttar Pradesh elections demonstrated, demonetisation had its supporters.

Then there was the Goods and Services Tax (GST), implemented from July 1, which seeks to create a seamless market in the country by making the flow of goods and services easier and more transparent. But the implementation of GST wasn’t without hurdles. It took enterprises, especially small and medium ones, a while to understand and transition to the new tax system.

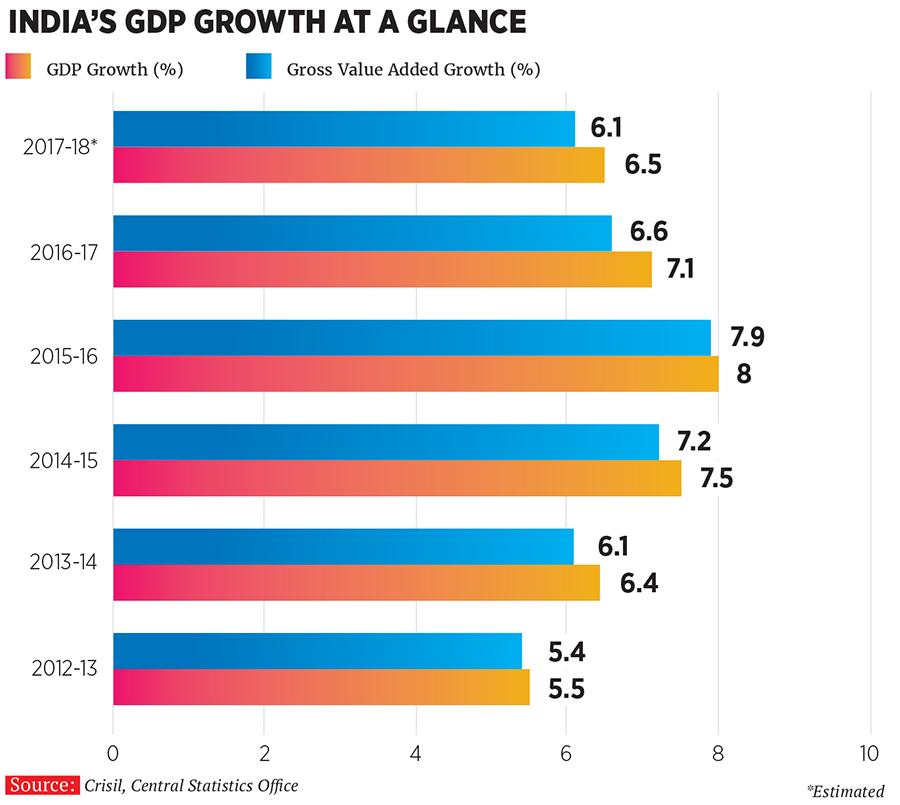

Demonetisation and GST, along with lower farm income, have led to estimates that India’s GDP will grow at its slowest pace in the last four years, with the Central Statistics Office estimating GDP growth in 2017-18 to be 6.5 percent, down from 7.1 percent in 2016-17.

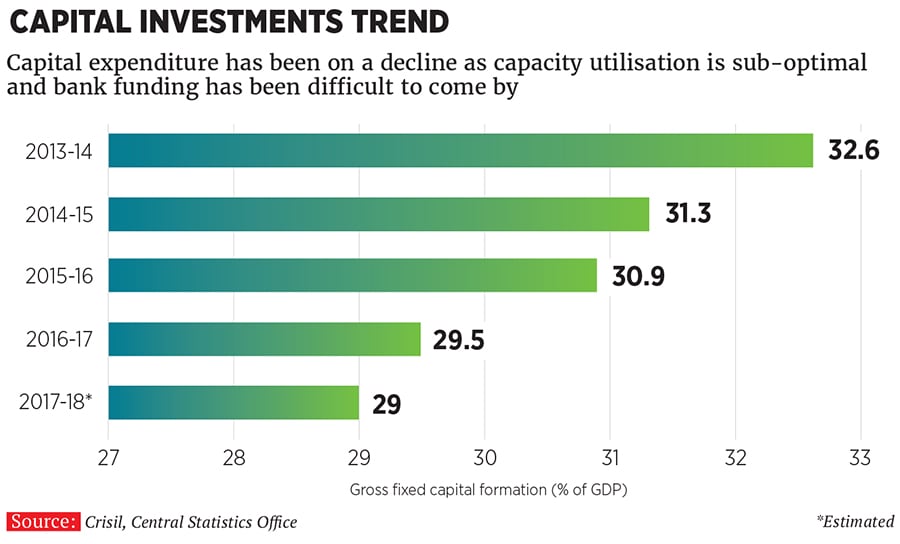

One of the key economic statistics that the government will take heart from is the Nikkei India Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which reached its highest level in five years in December 2017, indicating a revival in manufacturing activity through new domestic and export orders. But Goenka says the industry will plan new capital expenditure projects (that will lead to new jobs) only when existing capacity utilisation inches above 75 percent (it is around 71 percent at present). This is one of the reasons that new capex announced by Indian companies in December 2017, worth ₹77,000 crore was at its lowest level in 13 years.

Capacity utilisation will rise with increased demand and consumption. The expectation is that to bring some relief to the middle class (which bore the brunt of demonetisation) and to raise their disposable income (to boost consumption), the government could increase tax exemption limits for salaried individuals. To compensate for the consequent revenue loss, the government is widely anticipated to either re-introduce long term capital gains tax on listed securities or tweak the holding period that qualifies as long-term. At present, investors who buy and hold listed shares for over a year are exempt from paying long-term capital gains tax on the investment.

Aashish Sommaiyaa, MD and CEO of Motilal Oswal Asset Management, says he “won’t be surprised” if long-term capital gains tax is brought back in the Budget and this could lead to a 10-12 percent equity correction.

But the markets have been buoyant right through 2017 and a contrarian theory is that, since equities are so attractive, a long-term capital gains tax may not impact investor sentiment. There are other reforms with respect to direct taxes that the industry is expecting. Ranade reasons that if the government introduces long-term capital gains tax on shares in the Budget, it should do so across other asset classes such as bonds, real estate and private equity to ensure parity. “This will generate income for the government by widening the tax net,” he says.

Goenka agrees that the Budget should address the direct tax issue by rationalising rates and widening the base of taxpayers. One of the direct taxes that the industry hopes will be rationalised is corporate tax. India taxes the income of domestic companies at a rate of 30 percent (the effective tax rate comes to 33-35 percent). Soon after the current government came to power, Jaitley had stated that he expected the corporate tax rate to eventually fall to 25 percent, but that hasn’t happened.

“We need to simplify corporate tax and other direct taxes so that businesses don’t spend time micromanaging tax issues and run around for exemptions,” says Mariwala. Whether the finance minister can cut corporate taxes in an environment where there may be a fiscal slippage is debatable. But Mazumdar-Shaw points out that other economies, such as the US, are offering tax breaks to corporations in a bid to bolster the economy.

Agriculture versus industry, rural voters versus middle class voters, long-term sustainability versus short-term fixes, and economic prudence versus the compulsions of electoral politics—Jaitley will have to make many choices, and none of them are going to be easy.

In the end, Manish Sabharwal, chairman of TeamLease Services and a director on RBI’s central board sums it up when he says: “I think all budgets are political, because in India there is always an election coming. There is a difficult balancing of the short- and long-term, and hopefully the government will stay with its belief that a 10-year plan is not the same as 10 one-year plans.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X