The Reliance Juggernaut On The Move. Again!

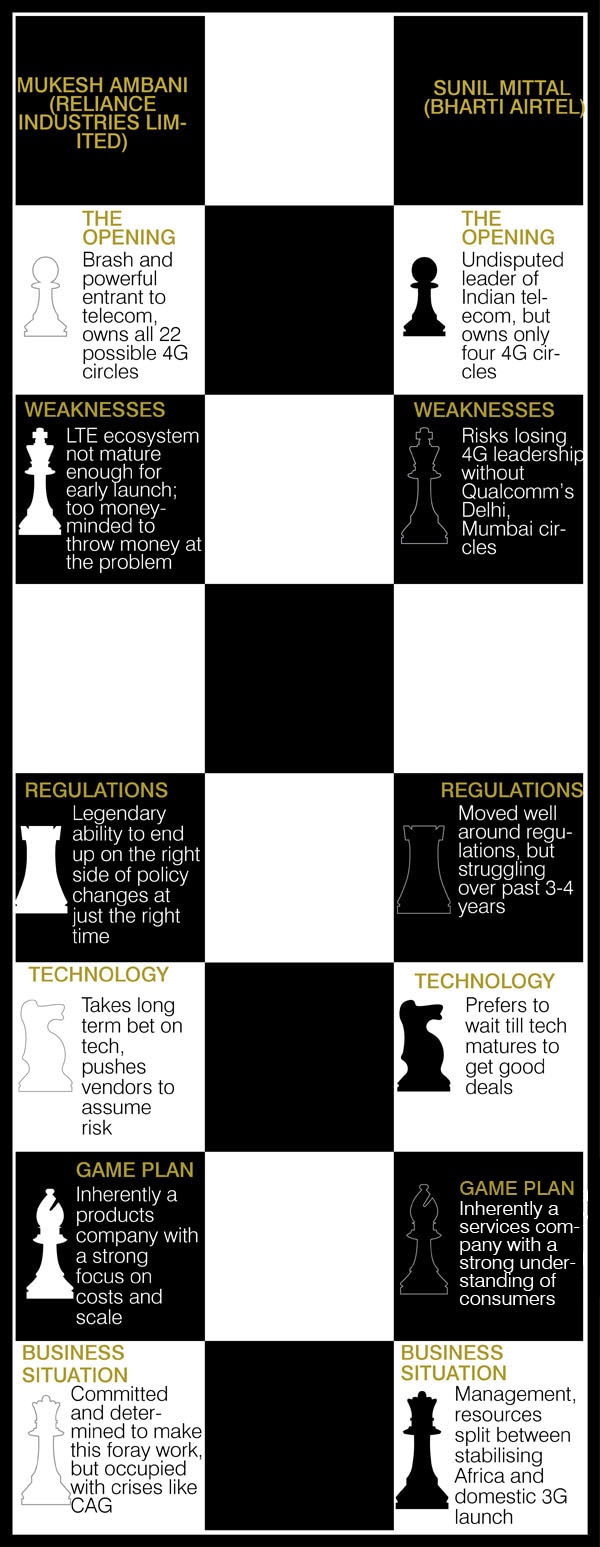

The first time Mukesh Ambani disrupted Indian telecom, Sunil Mittal survived, even emerged stronger. Can he pull it off a second time?

India, for Paul E. Jacobs — CEO of $11-billion telecom research and hardware company Qualcomm — has been like a box of chocolates, in a very Forrest Gump way. The good surprise came on June 11, 2010, when Qualcomm won the licence to offer broadband wireless access (BWA) in Mumbai, Delhi, Haryana and Kerala for $1 billion. The nasty one arrived on September 7, 2011, when the Department of Telecommunications rejected its application on flimsy grounds. “It was a silly technicality and the message being sent out by the government was: Even if you commit to investing $1 billion in India, you will be uncertain of your fate,” says B.K. Syngal, a 40-year veteran of Indian telecom and a principal with advisory firm Dua Consulting.

Jacobs was surprised, but it was Sunil Mittal, CEO, Bharti Enterprises, who must have been stunned.

Airtel was set to buy out Qualcomm’s spectrum, at least in Delhi and Mumbai, to roll out its fourth generation (4G) services. “For months, Airtel’s body language among vendors and partners suggested it viewed Qualcomm’s circles as its own,” says Kunal Bajaj, the India head of Analysys Mason, a telecom consulting firm.

But Qualcomm’s rejection meant Airtel would not be able to offer 4G services in Delhi and Mumbai till the issue is sorted out.

No one could be happier than Reliance Industries Limited (RIL). It is now the only company to have a licence to offer broadband in the very lucrative areas of Mumbai and Delhi.

All Your Data Belongs to Us

On June 11, 2010, little-known Infotel Broadband beat the biggies of Indian telecom to win spectrum in every geography on offer. Within hours it emerged that RIL would be buying Infotel for $1 billion. RIL would also make good to the Indian government the $2.7 billion that Infotel had bid for the spectrum.

It was a classic Ambani move — swift, stealthy and massive in scale.

Though it appeared rash and bullish, the move was merely the second step in a carefully laid plan by Mukesh Ambani and his trusted lieutenant Manoj Modi to re-enter the telecom sector. Step one was the May 23 burial of the four-year-old non-compete agreements between RIL and the Anil Dhirubhai Ambani Group, promoted by Mukesh’s estranged younger brother Anil, which prevented RIL from offering telecom services.

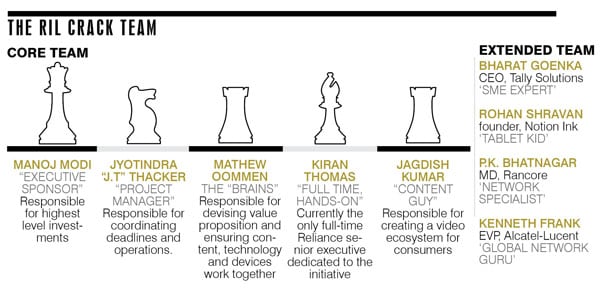

Like a tightly-scripted heist flick, a crack team of trusted individuals began arriving for RIL’s second telecom gamble. Most of them had worked with Ambani and Modi during their first, CDMA-based telecom foray.

Modi was the executive sponsor and responsible for highest level investments. Reporting to him was his brother-in-law Jyotindra ‘J.T.’ Thacker who moved up from his role as chief information officer at Reliance. Thacker would be the project manager, responsible for operations and deadlines. Then came Mathew Oommen, most recently chief technology officer at US-based telecom operator Sprint-Nextel. Oommen was the ‘brains’, responsible for creating compelling consumer offers, value propositions and ensuring content, technology and devices work together. Kiran Thomas, assistant vice president at Reliance, and Jagdish Kumar, a Star TV senior executive who came on board this April, completed the core team.

An equally key set of individuals came from outside Reliance, hand-picked and, in many cases, backed by Reliance investments. These included Bharat Goenka, the managing director of small and medium enterprise (SME) focussed software maker Tally; Rohan Shravan, the founder of tablet PC maker Notion Ink; P.K. Bhatnagar, the managing director of telecom network solutions company Rancore and Kenneth Frank, an executive vice president at telecom equipment major Alcatel-Lucent who heads a newly formed joint-initiative with Reliance.

Like his late father Dhirubhai Ambani, 54-year-old Mukesh takes a long term view of market potential and Reliance’s share in it. This time, his big gamble was on wireless data.

Laying a data cable to every Indian home is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Prakash Bajpai, founder and CEO of Tikona Digital Networks, a wireless broadband company that bought BWA spectrum in five geographies, says it costs between $1,200 and $1,500 to lay a dedicated optic fibre cable to a household. “The consumer isn’t going to pay more than $12 per month. Assuming you make 20 percent as the margin, think how much time it will take to recover the investment,” he says.

Offering wireless broadband wasn’t feasible up till now because most Indian mobile operators were busy selling voice telephony. Even when they tried to offer data, the speeds were woeful because almost all their wireless spectrum was clogged with voice traffic.

That is set to change as the BWA winners have got a healthy chunk of 20MHz of spectrum. In comparison, the 3G winners got 10MHz each.

Airtel’s Game to Lose

In the game of telecom, there are two trump cards that are very tough to outplay: A first mover advantage and a strong incumbent advantage. Combine the two and you’re as good as invincible.

That, ideally, was the situation Airtel should have been in. The undisputed leader in mobile voice telephony with impeccable credentials in enterprise data services and wired broadband, it was best placed to lead the 4G evolution. By combining its own BWA geographies — Maharashtra, Karnataka, Kolkata and Punjab — with Qualcomm’s, and a speedy rollout, Sunil Mittal would’ve assured Airtel of a nearly-undefeatable position.

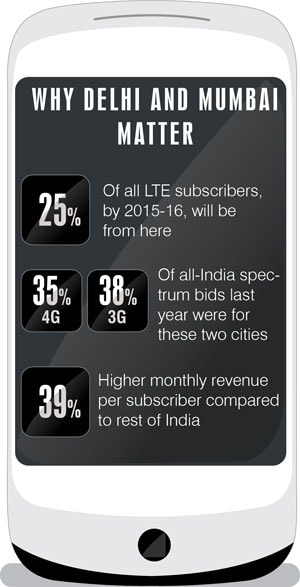

Key to those plans were Delhi and Mumbai, together representing 35 percent of all India 4G bids and 38 percent of 3G bids. Analysys Mason’s Bajaj says, by 2015-16, more than one in every four of the 25 million to 26 million long-term evolution (LTE) subscribers would come from these two cities.

But if Qualcomm is unable to sort out its license mess, it would be as if Reliance got a heaven-sent monopoly in these two markets. And the longer the mess lasts, the easier it is for Reliance to convert its advantage from first mover to strong incumbent, in the process inverting the existing pecking order of telecom.

For Mittal, this is doubly dangerous. His management is already stretched between handling cut-throat competition in Airtel’s 16 African country operations, and getting 3G to work in India. That’s very different from selling voice.

Airtel has always adopted mature technologies and innovated around operational aspects. But with LTE that is not an option because it is an emerging technology, with very few handsets or devices that support it. This of course plays to Reliance’s traditional approach of taking a long view on technology, like it did with CDMA a year ago, and using a dangling-carrot approach to get vendors to assume the risk of creating an ecosystem around it.

Then of course there is regulation. “When it comes to regulation, Airtel has been more successful at tactics than strategy, but tactics only go so far. In terms of regulatory vision, Reliance is perhaps the shrewdest,” says Mahesh Uppal, a telecom policy expert and director of consulting firm Com First.

Airtel’s 3G launch did not turn out as planned, says a telecom expert. First, it was unable to create compelling and easy-to-understand offers due to which adoption and usage was poor. Second, it had severe bandwidth issues.

In response to a query from Forbes India, Airtel said, “We do not comment on market speculation. However broadband and data remain an integral part of Airtel’s strategy.”

Over time, the entire data business has moved to USB dongles where Reliance Communications (RCOM), Tata Teleservices and MTS now have significant advantage. Even Vodafone is reselling MTS dongles.

Spending another billion dollars on Qualcomm’s licences, plus at least an equal amount to roll out services, is therefore not an easy call for Airtel. Its board is learnt to be questioning the wisdom of spending another $2 billion-odd on 4G when it was still unable to justify the nearly $3 billion it spent on acquiring 3G spectrum.

This was partly the trigger for a restructuring exercise within Airtel around June 2011. Airtel will need to do some serious resource and strategy balancing between improving its 3G services, which experts say will take 12-18 months, and moving ahead with 4G. Judging by its serious network trials in Chandigarh, Airtel seems to realise it too.

What has Ambani seen that Mittal hasn’t? The short answer: Video.

The Network

A few months ago, an RIL team cordoned off a Mumbai Café Coffee Day outlet while discussing plans with a vendor. Reliance is pushing vendors and consultants hard on solving what looks like an insurmountable problem: How do you disrupt the world’s most innovative and competitive telecom market? That’s why video matters.

Video offers multiple benefits. It is the easiest product, after voice, to sell to customers, while it throws up significant amounts of traffic.

Set top boxes that combine TV channels, on-demand video and video-conferencing are undergoing trials on Reliance’s pilot networks. “But for something disruptive to happen, the intersection of supply and demand should be there,” says Neeraj Aggarwal, a partner with the Boston Consulting Group. And it will take superb marketing to make that happen.

So, till video takes off, Ambani will need the support of the voice business. Voice still rules in the Indian mobile telephony market because of two key reasons: Getting subscribers to buy a new data-only device and service will be very tough; and Indian customers are quite accustomed to paying ‘linearly’ for voice minutes unlike data where they expect disproportionately lower fees as their usage shoots up.

But under 4G license conditions, Reliance cannot offer voice. Even if regulations changed to allow voice over IP (VOIP), it would be next to impossible for Reliance to match Airtel’s incremental cost of producing one minute of voice — 7 paisa!

Enter RCOM, which, in most likelihood, will allow Reliance to exclusively re-brand and re-sell its GSM-based voice services. A partnership with RCOM will also give Reliance access to its 50,000 cell towers to place its LTE base stations, and a pan-India optic fiber network.

So, when will the Reliance juggernaut roll into town?

The Delayed Onslaught

Reliance’s original plan was to launch 4G across seven cities on December 28, the late Dhirubhai’s birthday. That date has slipped, because the LTE device and ecosystem is immature and Reliance’s senior management has been tied up with serious issues, like the report by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India around its gas mining operations.

Lars Stork, the CEO of Augere Communications that won the 4G licence for Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, says he expects Reliance to launch services in at least four metros around the same time he does, April-June 2012.

The first wave will see consumers being targeted with plug-in USB modems, set top boxes that offer TV channels, indoor and outdoor modems and a few tablet PCs. Apart from Notion Ink, Reliance is understood to be in advanced negotiations with two Taiwanese brands to procure customised mass-market tablets priced around Rs. 8,000 to Rs. 9,000.

“Nothing will be off-the-shelf with most devices being made specifically for them,” says Sridhar Pai, the head of research firm Tonse Telecom.

Only from 2013 are we likely to see LTE-based phones from Reliance, simply because such devices are yet to mature and become affordable.

SMEs will be offered reliable broadband access through modems, with service level guarantees, cloud-based productivity and workforce applications like email, CRM and salesforce automation.

Hardware and software vendors, including Huawei, Alcatel-Lucent, Ericsson, HP and Cisco are falling over each other to get a piece of the Reliance pie. “The brilliant thing Reliance manages because of the scale of the opportunity is to get vendors to develop their ecosystem without signing binding deals. They did it during Monsoon Hungama too,” says Bajaj.

Consultants are being asked to design processes that can scale easily to millions of subscribers while remaining nimble. For instance, early discussions around signing up new customers sans paperwork explored the possibility of relying upon the Aadhaar UID.

However, the final launch strategy could still change, in all likelihood it will be relatively (for Reliance) low-key, in seven or eight cities, gradually ramping up to 35 towns within the first year and about 60-100 by the end of the second.

Still, much of these are still only plans. And, like Monsoon Hungama, even the best laid plans can end up like a millstone around your neck.

Unlike marketing-driven Airtel, Reliance is a product-driven company that thinks in terms of production cost. That sometimes blinds them from how consumers desire or use services. In a recent meeting with consultants, Ambani drew a small rectangular box on a whiteboard. “This is a box. It sits inside a consumer’s home and meets all of his information and transaction needs. I don’t know what is in it, but I want to be it.”

(Additional reporting by Shishir Prasad)

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)