Lupin's retail therapy

The pharma company's recent string of acquisitions is not just another bout of binge buying but a concerted effort to unlock the next phase of growth

For those who own a pharma company anywhere in the world with a promising portfolio of specialty drugs, here’s a tip: If you’re looking to sell, Lupin is buying. And on the seventh floor of Lupin’s headquarters in Mumbai’s Bandra-Kurla Complex, this sense of urgency is palpable. Founder and chairman Desh Bandhu Gupta’s children, Vinita, 47, (chief executive), and Nilesh, 41, (managing director), have a spring in their step, fresh off the back of announcing two acquisitions in as many days. The drug maker, which closed FY2015 with Rs 12,600 crore in revenue, has been on a shopping spree for a few years, snapping up mostly small-ticket companies across the globe. But Lupin garnered particular attention in July when it announced the $880 million-buyout of US-based generic drug maker Gavis, the biggest foreign acquisition by an Indian pharma company to date (the previous largest was by Dr Reddy’s Laboratories when it bought US-based Betapharm in 2006 for around $560 million).

“July is the busiest month we have had,” says Vinita, with a sense of satisfaction meshed with exhaustion. “We have had six acquisitions since January last year.” The CEO of Lupin is based in the US, but spends the better part of her time shuttling between countries in regions as diverse as North and South America, Africa and Europe where the company has business interests that she oversees. With Lupin stepping up the pace of its international acquisitions, her schedule has become even more hectic.

Her brother Nilesh is more homebound and doesn’t need to travel as much, except for routine trips to Pune where Lupin’s main research and development (R&D) facilities are located. In his own words, while Vinita takes care of everything to the left of India, he takes care of things in the country and everything to its right, referring to Lupin’s business interests in southeast Asian markets like Japan, and Australia. Operationally, Vinita is the one driving Lupin’s mergers and acquisition (M&A) strategy, while Nilesh is entrusted with the responsibility of maintaining the firm’s impeccable R&D and manufacturing capabilities.

While their roles differ, the siblings find common ground in their ambition to make Lupin a $5 billion-company (in sales) by fiscal 2018, and their chosen path to reach this goal—inorganic growth.

Vision 2018

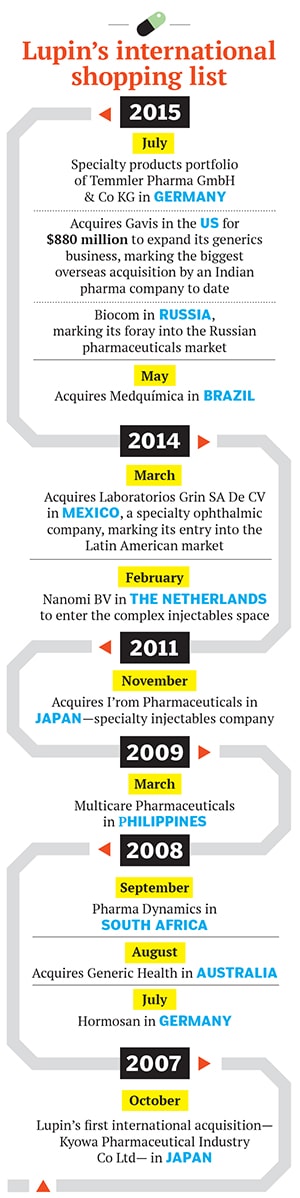

Lupin, India’s third largest pharma company by sales, made its first international acquisition in Japan in 2007; that of a company called Kyowa. It was the first time that the company made its intention to grow inorganically overseas evident. Since then, it has made a few more acquisitions, but it stepped on the gas with respect to buying foreign assets around two years ago.

To outsiders, Lupin’s acquisitions may appear to be a case of binge buying. Consider that half of the 12 companies acquired by Lupin to date have been bought over the last one-and-a-half years. Some concerns have been raised whether Lupin, a debt-free company, should take on debt to fund acquisitions like Gavis. But Vinita and Nilesh, their 77-year-old father (he attends office every day for six hours and takes a few meetings), and Kamal K Sharma, 66, former managing director and current vice chairman, are of the view that these purchases are part of a long-term strategy to unlock the next phase of growth. These purchases are part of Lupin’s ‘string of pearls’ strategy in which it buys companies that are smaller in size but offer access to a portfolio of drugs it doesn’t have, or to new technology and markets.

“We determined a couple of years ago that we want to achieve a turnover of $5 billion (around Rs 31,875 crore) by fiscal 2018,” says Vinita. “We did our strategic planning and determined how far we can get organically. We knew there will be a gap that would have to be bridged through acquisitions.” Vinita and Nilesh want the firm to achieve this growth in turnover while keeping net profit margins at the current level of 19 percent at least, implying a targeted net profit of around Rs 6,056 crore by FY2018.

According to Nilesh, a fifth of the $5 billion-turnover that Lupin is targeting would come from companies being acquired around the globe. His confidence isn’t misplaced: Lupin’s international bets are getting bigger and bolder and, as he points out, the combined value of all the acquisitions made prior to Gavis over the last eight years are approximately equal to the $880 million that it paid for its single most expensive acquisition to date.

But Lupin’s future acquisitions aren’t likely to be as expensive as the Gavis deal, though they won’t be insignificant either. “We may spend another $500-700 million over the next one year but we are not going to spend another $1.5 billion, because that would be overleveraging the company,” Nilesh says.

Though Lupin has been a debt-free company for the last couple of years, Vinita and Nilesh aren’t averse to taking on some debt in order to finance, what they believe, will be the future growth drivers for the company. According to Nilesh, Lupin’s debt-to-equity ratio may stand at 0.5:1 after it raises funds to predominantly finance the Gavis deal. Vinita also points to the current low cost of debt in international markets as an attractive proposition to fund global acquisitions.

The cost of borrowing for the Gavis deal, for which Lupin has tied up short-term debt with JPMorgan Chase, would be around 2.5-3 percent, according to Sharma. He also adds that while Lupin has the headroom to accommodate a debt-to-Ebitda (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation) ratio of 3:1, it will only stretch itself as far as a comfortable 1.2:1, which will put it in a good position to service its debt obligations. The company intends to subsequently refinance the short-term debt with borrowings that will mature over a longer period of time.

Its current position in the industry will be buoying its risk-taking ability too. For a company that entered the American market in 2005 to underscore its value to investors, Lupin has made its point loud and clear. According to its latest investor presentation, it is the third largest among Indian pharmaceutical companies by total sales (Sun Pharmaceuticals, which acquired and merged Ranbaxy with itself is the largest Indian company by sales, followed by Dr Reddy’s) and the sixth largest drug maker among all pharma companies in the US by prescriptions.

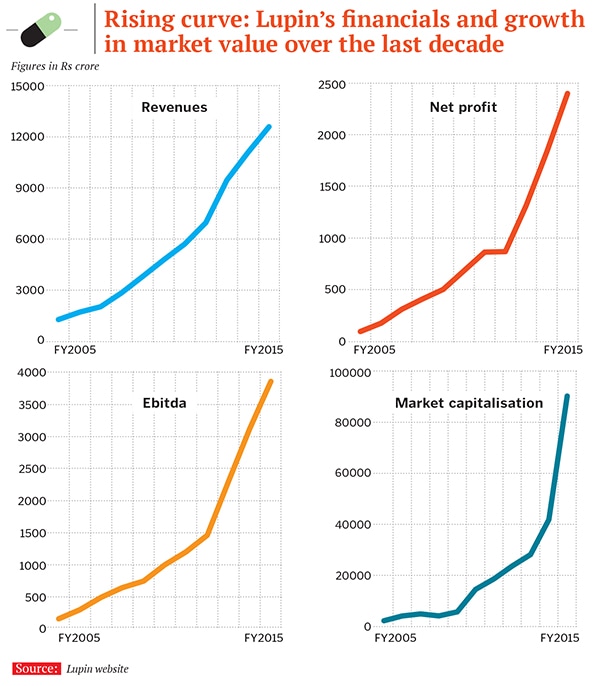

In fiscal 2015, Lupin had a turnover of Rs 12,600 crore and a net profit of Rs 2,403 crore. It reported a net profit margin of 19 percent.

The Guptas are unfazed. After all, over the last five years till FY2015, Lupin’s revenues have grown at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.42 percent; net profit has grown at nearly 29 percent annually over the same period. In the last two years, the company’s turnover has grown at a CAGR of 15.4 percent (the lower growth rate has come on a higher base), but net profit rose at a much faster clip of 35.23 percent. The market clearly appears to approve of Lupin’s strategy to grow bigger internationally through acquisitions. In FY15, Lupin’s market value more than doubled to Rs 90,275 crore (as on March 31).

However, the company’s market value has since declined to around Rs 76,353 crore as on August 11. This can be attributed in part to a subdued quarterly earnings performance over the March and June quarters. Earnings were impacted by the pressure on profit margins due to a consolidation among drug distributors in the US, who now have greater bargaining power when it comes to deciding prices. The other factor is a significant slowdown in the rate at which the US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has been approving applications for the launch of new generic drugs; this has meant that generic drug makers like Lupin have faced delays in monetising their product pipelines.

Gavis to the rescue?

And that is where the importance of Gavis comes in.

“The idea behind the [Gavis] acquisition is a mix of expanding our pipeline, having more shots on goal (with reference to the success rate of winning approvals from the USFDA) and bringing in a more comprehensive portfolio to the market,” Vinita says, alluding to the challenges facing generic drug makers in the US. Lupin’s management expects the Gavis transaction to close in the December 2015 quarter and anticipates it to be EPS (earnings per share) accretive in the first financial year after the acquisition itself.

The New Jersey-based company adds around 20 high-margin, generic products to Lupin’s portfolio and takes the total number of products that the company will immediately market in the US to 101. Additionally, post the Gavis acquisition, the total number of Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) that Lupin has pending with USFDA rises to 164, which is the fifth largest ANDA pipeline for all pharma companies operating in the US and which gives it an addressable market size of $63.8 billion.

Gavis reported an Ebitda of $35 million in 2014, with a healthy operating profit margin of 36 percent.

Lupin also inherits a manufacturing plant in the US; this means it can tap the government business there, something it could not do as long as it was exporting drugs from India.

“For the current fiscal, we are expecting some major approvals [to launch new generic drugs],” Vinita says. If they come through, then, along with Gavis’s earnings, the second half of the current fiscal will look much better for Lupin.

These are happy outcomes of Lupin’s M&A strategy which had been devised keeping exactly these factors in mind. The first was access to products that it doesn’t make and which are complementary to its existing portfolio. Nilesh points out that one of the areas where Lupin doesn’t have an adequate presence is specialty drugs (which are needed to treat complex ailments). Case in point: The acquisition of German firm Temmler Pharma GmbH and Co KG’s specialty products portfolio, announced a day after the Gavis acquisition was made public, aimed at securing a basket of therapies that Temmler had developed for central nervous system disorders and drugs that treat rare illnesses like Huntington’s disease.

The next acquisition that Lupin is considering on a priority basis is that of a specialty drug manufacturing entity in the US, an area in which Lupin does not have a strong presence there, says Nilesh.

The second factor is access to new technologies like complex injectables and controlled substances (which have the potential for abuse and which are regulated under the federal Controlled Substances Act in the US). Consequently, Lupin acquired Nanomi BV in The Netherlands in February 2014 to enter the complex injectables space for the first time; meanwhile, the Gavis acquisition gives Lupin a manufacturing site in the US from where it can supply controlled substances to the local market.

(Controlled substances cannot be imported into the US and, hence, have to be produced locally.)

The third angle to its M&A strategy is geographical reach. Lupin has acquired companies in countries such as the US, Japan, Russia, South Africa, Australia, Brazil and Mexico. It is also looking at China and India as well as at some countries in eastern Europe for future acquisitions, says Nilesh. The US, India and Japan account for around 80 percent of Lupin’s business at present. (In FY2015, US accounted for 45 percent of revenues, India 24 percent and Japan 10 percent.) While Lupin’s business in the regions outside these three countries is smaller, the company has carved a place for itself in some of the markets like South Africa where it is the fourth largest generic drug supplier.

An inspiring past

The strength of the existing platform that enables Lupin to chase inorganic growth, as well as appreciate the need for it, is drawn from the company’s past, particularly the last decade.

Lupin, named after a flower that nourishes the land it grows on, was founded in 1968 by Desh Bandhu Gupta, a professor at Birla Institute of Technology and Science, Pilani. Though it started as a vitamin company, Desh Bandhu’s ambition was to make drugs that combat life-threatening diseases in India; eventually, Lupin emerged as the leading manufacturer of anti-tuberculosis drugs.

The company remained focussed on the Indian market and diversified into real estate in the 1990s. This proved to be a bane for the company that found itself saddled with debt, while the singular India focus meant that rivals like Cipla and Ranbaxy stole a march on Lupin in terms of establishing their place in international markets.

Desh Bandhu had to sell his stake in the company to pare the debt; a chunk (around 12.55 percent) of his holding was bought by CVC International, a Citigroup company, in 2003. The new investors wanted the managing director to be from outside the promoter group to steer the company going forward. Enter Kamal K Sharma (this was his second stint at Lupin, after spending time at RPG Life Sciences), who has been credited with helping Lupin transform from an India-focussed, anti-tuberculosis drug-making company to an international generic drug maker with a presence in large pharmaceutical markets like the US and Japan.

Sharma and Desh Bandhu worked together to put Lupin back on the growth path, through a process that was christened ‘creative transformation’. This entailed investing greater sums of money in R&D (Lupin invests around 10 percent of its turnover in R&D) to develop a product pipeline that would help give Lupin clear niches to play in. Subsequent to this, Lupin established strong competency in therapies for cardiovascular, diabetology, asthma, paediatrics and gastrointestinal-related disorders, among others.

While the company waited for its R&D activities to bear fruit, Sharma enforced strict control on costs, brought in prudent accounting policies and focussed on managing the supply chain in a manner such that high quality products were assured to clients in the US at a near 100 percent fill-rate throughout the year.

He also oversaw the process with which Lupin started doing business in the US by selling a branded drug, Suprax (for which it held exclusive rights at that time), as opposed to plain vanilla generics. Not only did this give a substantial fillip to the company’s earnings, it also enhanced Lupin’s reputation as a pharma company in the US. Suprax developed into a brand that earned Lupin around $80-90 million and captured a share of around 80 percent of the prescription market in its category. (It, however, lost exclusivity earlier this year; other companies are free to make generic versions of the drug and sell it in the US market.)

“Lupin has executed well on its US business over the last few years (CAGR of 30 percent over the last five years) despite being a late entrant in the market,” a JP Morgan report dated June 23 states. “The investment in its ANDA pipeline has delivered key exclusive launches, market share gains and margin expansion.”

Sharma also led Lupin’s foray into Japan, which is the second largest market for Lupin at present. He tells Forbes India that Lupin decided to enter Japan at a time when no other major generic drug maker had attempted tapping the market. This was a result of its burning desire to be the number one Indian company in at least one major pharma market in the world.

Spectacular Growth

The result of all these initiatives has seen spectacular growth in the company’s earnings. Between 2004-05 and 2014-15, Lupin’s revenues have grown at a CAGR of 26 percent; net profit has grown at 38.5 percent; and the company’s market value has risen 45 percent annually.

In FY2012, Lupin had a net debt of Rs 1,236.64 crore (according to Capitaline), but is now debt-free. It has been able to achieve this by successfully integrating the operations of the companies it acquired with itself and generating cash from the consolidated business.

As a result, a solid foundation was laid for Nilesh and Vinita to build upon when they assumed day-to-day responsibilities of running the company in 2013.

They would be heartened to hear that one of the oldest investors in the company believes in the current management and its vision. Billionaire investor Rakesh Jhunjhunwala has remained invested in Lupin over 15 years and patiently so. “There have been two-three periods in the last 15 years when Lupin has yielded no returns. But I didn’t sell. I am bullish on the company and I am bullish on Indian pharma,” Jhunjhunwala tells Forbes India. “Desh Bandhu Gupta is a nice human being, his children are very capable and level-headed. They have good people working for them and I trust the management. At the end of the day, it’s all about the people.”

Jhunjhunwala adds that he isn’t perturbed by the kind of money Lupin intends to spend on acquisitions; he is convinced the management wouldn’t spread the company’s resources too thin. And it is not like the duo at the helm isn’t aware of the pace at which they are running. As Nilesh puts it, “Obviously we have bitten a lot at this point in time [in terms of acquisitions], but a lot of this was catch up for the past.” Safe to say, another day, another announcement may continue to be the mantra at Lupin.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)