Life after Layoffs: How employees can get back on their feet, and what companies can do

Amid a spate of layoffs, including overnight or unceremonious firings at IT companies and startups, experts weigh in on the rights employees can exercise, how they can fight back or pick up the pieces

The past few months have been difficult for people working in the private sector in India, particularly for employees of tech companies. It’s not just the startups that are laying off people, but also storied IT services organisations. Illustration: Chaitanya Surpur

The past few months have been difficult for people working in the private sector in India, particularly for employees of tech companies. It’s not just the startups that are laying off people, but also storied IT services organisations. Illustration: Chaitanya Surpur

When social media platform Twitter was firing hundreds of employees in India as part of the global layoffs initiated by its new owner Elon Musk earlier this month, Tarun Shah (name changed), an employee with an AI startup, was also handed the pink slip. The startup had suspended its India operations overnight.

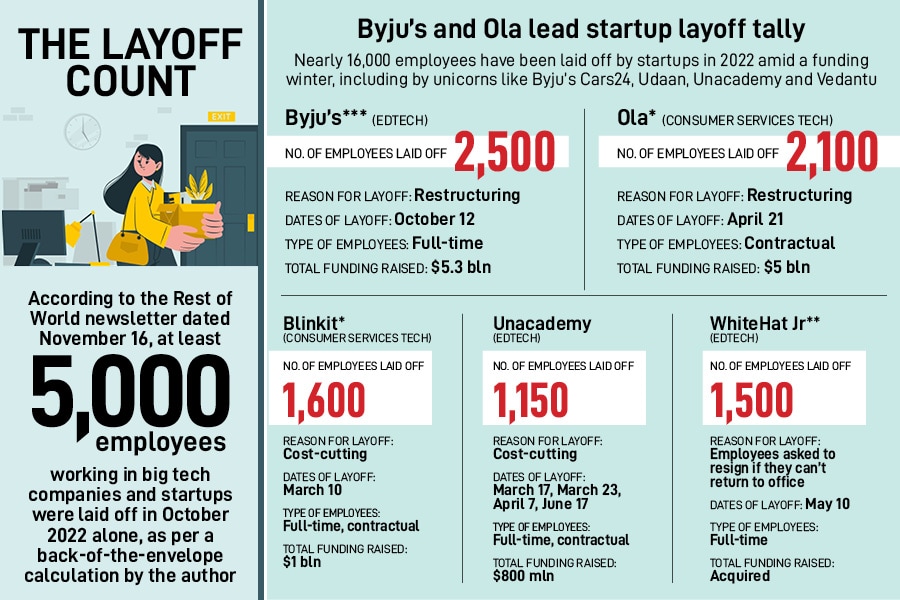

Shah became another statistic along with the 16,000-odd employees working in tech companies in startups who have lost their jobs this year as part of mass—and in many cases, sudden—layoffs announced by their respective companies.

Shah says his company gave him no advance notice, the leadership held no meetings or town-halls with employees, and there was just an email and a call from HR saying they had been relieved from their duties with a few weeks of severance, and were not required to come to work from the next day.

“When things are going good, companies call employees their family. But this culture changes as soon as things are not going good,” says Shah, 25, who is an engineer with a degree in computer science. “Job security, even for skilled employees in the supposedly fail-safe tech sector, seems like a joke these days. All jobs come with a certain element of risk,” he says, adding that now he is in the process of applying to tens of companies and giving interviews on a daily basis. People on social media—who have been offering their support to people affected by layoffs—have been helping him with multiple job leads. But now, the way Shah approaches a prospective employer has changed.

While earlier he used to prioritise the role and take a company’s promises about the job and their work culture at face value, now he questions them a lot more. “I not only look at their product, but also their financials. If am not convinced about the stability of a company, that’s a no-no for me,” says Shah, who explains that after his layoff experience, he has started prioritising his personal security and growth above all else.

The current wave of layoffs has particularly seen support networks and communities of people being formed on social media, which help employees who have been laid off in a variety of ways: From helping them negotiate severance to finding new job leads to expressing criticism towards companies that have fired people unceremoniously or without following due protocol.

The current wave of layoffs has particularly seen support networks and communities of people being formed on social media, which help employees who have been laid off in a variety of ways: From helping them negotiate severance to finding new job leads to expressing criticism towards companies that have fired people unceremoniously or without following due protocol.

The UK and Europe have been seeing the unionisation of tech sector employees in order to help people with issues such as salary bargaining rights and unceremonious firing. In India, unionising has been largely elusive in the tech sector. Sundar, a professor at XLRI, Xavier School of Management in Jamshedpur, says the impression among companies and investors is that having unions works against the tenets of attracting capital and scaling up.

The UK and Europe have been seeing the unionisation of tech sector employees in order to help people with issues such as salary bargaining rights and unceremonious firing. In India, unionising has been largely elusive in the tech sector. Sundar, a professor at XLRI, Xavier School of Management in Jamshedpur, says the impression among companies and investors is that having unions works against the tenets of attracting capital and scaling up. When the first list of Fortune 500 companies came out in 1955, the life expectancy of Fortune 500 companies was around 64 years, and now is it close to 15 years, Sabharwal explains. At the same time, the average life expectancy of people in India is close to 70 years. “Companies don’t live forever. What is the value of a pension promise from a company that is only going to live 15 years? It’s a promise it can’t fulfil,” he says.

When the first list of Fortune 500 companies came out in 1955, the life expectancy of Fortune 500 companies was around 64 years, and now is it close to 15 years, Sabharwal explains. At the same time, the average life expectancy of people in India is close to 70 years. “Companies don’t live forever. What is the value of a pension promise from a company that is only going to live 15 years? It’s a promise it can’t fulfil,” he says.