Bankruptcy, experience, and wisdom: Hemant Jalan's Indigo Paints stint is not for the faint-hearted

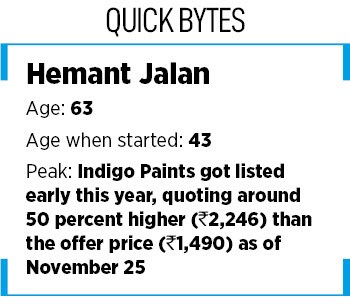

Staring at a bankrupt venture after a decade, and starting up in his 40s, Hemant Jalan always knew he was an entrepreneur at heart, and he was willing to bet on it. Frugal, practical but bold, the 63-year-old founder's venture had a blockbuster IPO this year

We have come a long way. But we have a long way to go.” Hemant Jalan, chairman and managing director, Indigo Paints

We have come a long way. But we have a long way to go.” Hemant Jalan, chairman and managing director, Indigo Paints

Image: Varun Kulkarni for Forbes India

You want to start a venture. Right? And your heart says that you are not cut out for a job. Okay, so before you take the plunge, why don’t you ask a question and see if you are fit for entrepreneurship? “Step back for 5 minutes,” urges Hemant Jalan, 63, founder of Indigo Paints, to all aspirants whatever age they may be. “Now think, if this venture goes horribly wrong, how far does it set you back?” he asks. Remember, he stresses, the venture doesn’t only go wrong. “It goes horribly wrong.”

Back in 1985, a young Jalan—in his late 20s—didn’t ask this question. In fact, it never crossed his mind. “I had brash confidence, and had succeeded in everything till then,” he recalls. After completing his BTech in chemical engineering from IIT-Kanpur, Jalan went on finish his master’s from Stanford University and an MBA from Chicago Booth School of Business. Armed with degrees and knowledge, he set up a couple of small-and-medium-sized chemical manufacturing companies in Patna. Twenties, he reckons, is more likely an expected age to turn founder.

A decade later, in 1995, he encountered technical problems in his manufacturing equipment. “The largest unit that I had set up completely failed. It was a big fiasco,” he recounts. The setback was massive. Jalan was driven to the brink of bankruptcy, and was forced to sell all his assets, including his house and car. “I was left with nothing,” he rues, adding that the trauma was not over; he still owed a lot of money to banks.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

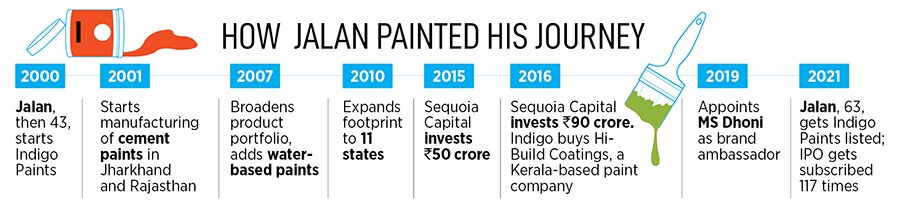

Next, he shifted to Pune, Maharashtra, and worked as management consultant for a year. The short stint helped him gather his thoughts, discover that he still had a small chemical unit in some kind of working condition in Patna, and decide about his future. In 2000, he started Indigo Paints. “I had no clue where this journey would take me,” he confesses.

Next, he shifted to Pune, Maharashtra, and worked as management consultant for a year. The short stint helped him gather his thoughts, discover that he still had a small chemical unit in some kind of working condition in Patna, and decide about his future. In 2000, he started Indigo Paints. “I had no clue where this journey would take me,” he confesses.

After six years, for Jalan and Indigo Paints, it was not a question of survival. The point was to gather pace. “It took us 10 years before we could start paying salaries on time,” he says. The brash confidence of the 20s, he underlines, now got tempered with high doses of reality.

After six years, for Jalan and Indigo Paints, it was not a question of survival. The point was to gather pace. “It took us 10 years before we could start paying salaries on time,” he says. The brash confidence of the 20s, he underlines, now got tempered with high doses of reality.  A big failure, he reckons, is the greatest learning, and a huge blessing. When it happens, it feels like the end of the world. But later, when one introspects, one can see how hard lessons pave the way for future success. One might be justified in accusing circumstances, but the unkind blows are blessings in disguise. “It helped me make more right decisions than wrong ones at Indigo,” he says.

A big failure, he reckons, is the greatest learning, and a huge blessing. When it happens, it feels like the end of the world. But later, when one introspects, one can see how hard lessons pave the way for future success. One might be justified in accusing circumstances, but the unkind blows are blessings in disguise. “It helped me make more right decisions than wrong ones at Indigo,” he says.