India INClusive: LGBTQ+ inclusion at the workplace still a work-in-progress

Two years after a historic judgment by the Supreme Court, companies are realising that the case for LGBTQ+ inclusion is stronger than ever, even as tackling underrepresentation, stereotypes and biases remain a work in progress

Most companies still seem to hire transgender people without fully Understanding what it means to be us: Harsha Hayathi, technical analyst, ANZ

Most companies still seem to hire transgender people without fully Understanding what it means to be us: Harsha Hayathi, technical analyst, ANZImage: Pankaj Sethia

It was August 2018, a month before the Supreme Court (SC) scrapped Section 377, a colonial-era ban on gay sex. Harsha Hayathi went up on stage at an inclusion seminar organised by her financial services company ANZ in Bengaluru, and mustering all the courage she could, said, “I am Hayathi. Though I was not assigned female at birth, I identify as a woman. Some women have short hair, I am that woman. Some women have husky voices, I am that woman. Some women have xy chromosomes, I am that woman. Some women cannot give birth, I am that woman. Even if you accept me or not, I am a woman.” For the first time in her professional career, Hayathi had brought her full self to work.

Before that, the 31-year-old transwoman had to change seven jobs in seven years because of fear, discrimination, ill health and gender dysphoria [a conflict between a person’s physical gender and gender with which they identify]. While she finally found acceptance through supportive colleagues and a robust policy framework at her current company where she works as a technical analyst, Hayathi believes that queer inclusion in India Inc is a half-written story.

“Most companies still seem to be hiring transgender people just for the sake of it, to tick boxes, without fully understanding what it means to be us or the challenges we face,” she says. According to her, organisations can only claim to be truly inclusive when everyone, right from business leaders to the cafeteria staff, are sensitised; only when they create supportive infrastructure from comprehensive health benefits to all-gender restrooms that help queer individuals feel secure and be themselves.

The history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer+ (LGBTQ+) individuals in India, beyond court cases and legal battles, is peppered with personal stories, mobilised community efforts, building of literary, media and archival resources, and social gatherings. The need to find employment avenues, financial security, career mentorship, nurture aspirations and stand up on their own feet has always been central to these efforts.

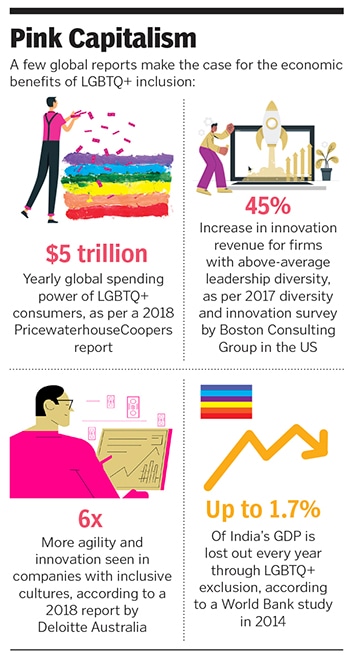

There is no recent official demographic data on the exact number of LGBTQ+ individuals in the country, though a 2014 case study conducted in India by Lee Badgett for the World Bank, titled ‘The Economic Cost of Homophobia’, estimated India would lose up to 1.7 percent of its GDP every year through LBGTQ+ exclusion, which was approximately $30 billion at the time.

Parmesh Shahani, vice president of Godrej Industries and the head of Godrej Culture Lab India, says many progressive companies had identified the case for inclusion since the early 2000s. Some organisations began the journey after the 2009 Delhi High Court judgment [which ruled that Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code is unconstitutional]. This momentum slowed down after a 2013 judgment reversed the 2009 order and made companies nervous.

“There was nothing in the judgment that said companies cannot stand by their queer employees, but corporate India, in general, tends to play safe,” Shahani says. But the SC verdict on September 6, 2018, upholding the rights of the LGBTQ+ individuals, freed the fence-sitting companies. “It unleashed a positive energy that had been built over the past decade. Indian companies are not homophobic, just ignorant. I am fine with that, because you can dispel ignorance with information.” Shahani believes organisations are still in the initial stages of the inclusion journey, which is why they must learn best practices from each other, especially from the early adopter companies, and evolve their policies accordingly.

One such early adopter is global IT services firm Accenture. According to Lakshmi C, managing director, lead—human resources (HR) at Accenture in India, the company was the “first to introduce medical cover for gender reassignment surgery way back in 2016”. She says the company has invested in building programmes to attract, retain and grow a diverse workforce, sensitise leaders through sessions and make efforts to enrol more people who can be allies to LGBTQ+ employees. They have also started a “six-month internship programme to build a skilled pool of transgender candidates”, Lakshmi says.

Another IT services firm Infosys has hired LGBTQ+ members across roles and hierarchies, including as software engineers, project managers, design and communication experts. The iPride employee resource group (ERG) at the company has, over the years, introduced gender-neutral washrooms across their India campuses, created learning resources for awareness, facilitated sharing of personal stories through the Infosys TV and intranet, and institutionalised health policies. “This includes partner coverage for medical insurance; gender confirmation surgeries, surrogacy and egg freezing and mental health,” says a company spokesperson.

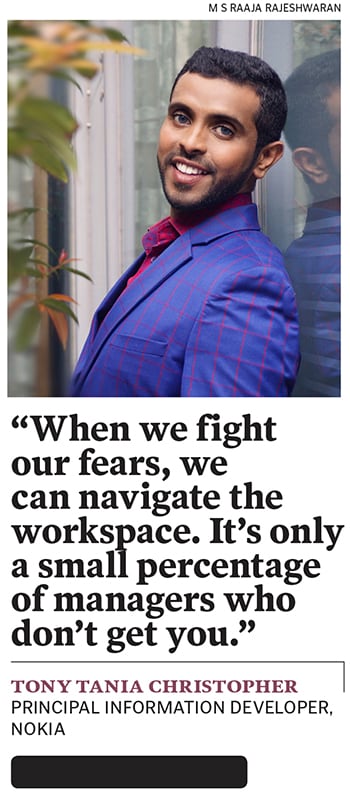

It was while he was a techie at Infosys that Tony Tania Christopher came out as gay in 2016, after many years of pretending to be straight. A progressive inclusion cell was one of the biggest reasons for him to stick with the company for over five years, says the 35-year-old Bengaluru resident, who has just made a career shift to Nokia. Coming out boosted his self-confidence and increased his workplace productivity, Christopher explains.

“When we fight our fears, we get the strength to navigate the corporate workspace. Of course, there will always be managers who think LGBTQ+ individuals do not fit in some roles or opportunities abroad, or for facing business clients, but it is a small percentage.” According to Christopher, instead of fearing the lack of professional growth as a reason to not come out, LGBTQ+ individuals can choose to walk out of a company that does not accept them as they are and work only for those that understand and value them. That said, he admitted that coming from a privileged background definitely makes the journey easier.

Skin in the Game

Experts suggest that companies have to do a lot more than policy provisions. Lawyer Aravind Narrain, a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum and an expert on LGBTQ+ rights, points out that the 2018 judgment had non-discrimination at the core. This involved, he says, working against stereotypes like queer people being problematic individuals, among other things. “In a corporate setting, these stereotypes are often reinforced in places that are most difficult to reach, like cigarette breaks, around the water cooler etc when you make fun of people based on these stereotypes, even if it is casual. Dealing with it will require a deeper level of work by companies.”

Christopher agrees, saying people at the workplace might have wrong impressions about the community, perpetuated by society and stereotypes from popular culture like Hindi cinema. “People are usually awkward and do not know what to say. For example, they do not talk or inquire about our partners as normally as they would do with a straight colleague,” he says.

Even seemingly casual, mild or innocent homophobia and transphobia has to be taken seriously, says Sophia David, who works with the leadership development team of a global consultancy firm in Hyderabad and identifies as a transwoman. “Ignored instances of casual homophobia could soon turn into an acceptable work culture,” she says, explaining that normalising the conversation is as important as having policies that also spell out corrective measures against repeated offences.

Normalisation includes paying attention to the simplest of things, like addressing people with their preferred pronouns, drawing from the lived experiences of queer employees while framing policy, being careful not to ask insensitive or intrusive questions and even using gender-neutral language. “For example, instead of starting a meeting with ‘Ladies and gentlemen’ or ‘ Hello guys’, say ‘Hello folks’ or ‘Hello distinguished guests’,” says Sophia, who advocates a top-down approach for implementation of LGBTQ+-friendly measures.

When leaders go out of their way to invest in the welfare of queer employees, it sets the tone for the company culture, says Swati Rustagi, director of HR at Amazon India Operations. Since 2017, the ecommerce company has an affinity group comprising members of the community and other allies. About two months ago, it launched a hiring programme specifically for transgender individuals. “An inclusive culture fundamentally fosters innovation. Without reflections and perspectives from various communities that make up society, you will tend to create programmes or products that are not relevant for your consumers,” she says.

Sophia also calls for policies to be flexible enough to evaluate on a case-by-case basis. Being a cancer survivor, she has to get her gender transition surgery in Thailand where she says doctors have the required expertise. But the insurance policy at her organisation would not cover the costs in this case, which is why her friends have helped her set up a crowdfunding campaign on Milaap to meet expenses. “I know that many treatments, including those for HIV, come at a cost. But they are necessary for LGBTQ+ folks,” she says.

Some companies do consider the flexibility aspect. Ecommerce platform Flipkart, for instance, has introduced a FlexBen programme, which, according to Chief People Officer Krishna Raghavan, offers “greater flexibility and freedom of choice in selecting and funding employee benefits, allowing them to customise their benefits package based on their individual needs”. The company’s insurance plan covers gender affirmation surgery and surrogacy procedure for LGBTQ+ employees.

Bridge the Gap

Neelam Jain, founder and CEO of PeriFerry, a startup that focuses on economic empowerment of transgender individuals, says she deals with cases where trans professionals, especially at the mid- or senior levels, still fear the consequences of coming out. Some of them have also faced opposition at the workplace when they wanted to undertake gender transition. Job profiles and roles for them are also restricted.

“Many organisations are still not comfortable having a transgender person as a leader or a manager. It’s ironic, because they would like to see a trans individual in the organisation at a junior level, but not really as a leader,” says Jain, who believes real change will not happen unless companies visibly bring people from the community at various levels in the workforce and have them work alongside other employees on a daily basis.

PeriFerry has created jobs for over 170 transgender individuals, including Hayathi, who have been placed across more than 75 corporates. The bootstrapped startup is currently working with 1,200 active trans job seekers, and Jain has noticed a serious gap where trans people often do not meet all the skill requirements listed out by companies. Hence, she helps upskill job-seekers as well. Jain says most trans employees are tenacious and hardworking, so “companies need to take a call about whether they would like to invest in skill training”.

Rustagi of Amazon India suggests that since it cannot be left to individual employers to address skill gaps, there is scope for public-private partnership. “NGOs, government and private players can come together to sort this out at the bottom of the pyramid, and create opportunities for people to access education and skills early in life so that they can find the right job.”

Lawyer Narrain calls for a comprehensive anti-discrimination legal framework in the private sector, mandated by the central government. “Something on the lines of the sexual harassment law, which will tackle discrimination, biases and prejudice at the workplace on the basis of gender orientation and sexual identity.”

While companies do not make it mandatory to disclose gender identity or sexual orientation, many queer individuals advocate coming out in order to leverage corporate policies in a better manner. Ketty Avashia, director at a multinational investment banking and financial services firm, who identifies as transgender lesbian, says he wants community members to grow on the basis of their skills, without worrying about their identity or orientation.

“There will always be quotas or targets for hiring squads put around by companies to get LGBTQ+ members and meet ground needs of diversity numbers. But in the absence of identifiable queer individuals, no real opportunities would be created for people to learn, adapt and practice inclusion,” he says. “So if we want to be indifferent to differences, it has to be a two-way street.”