I feel overwhelmed with television or public speaking. Books help me express myself: Vikas Khanna

On Forbes India's podcast From the Bookshelves, the Michelin-starred chef speaks about his recent book that's being made into a film, how his grandmother's kitchen shaped his formative years in cooking, why he jumps across genres as a writer, and being driven by the need to constantly remain inspired

Michelin-starred chef, Vikas Khanna

Michelin-starred chef, Vikas Khanna

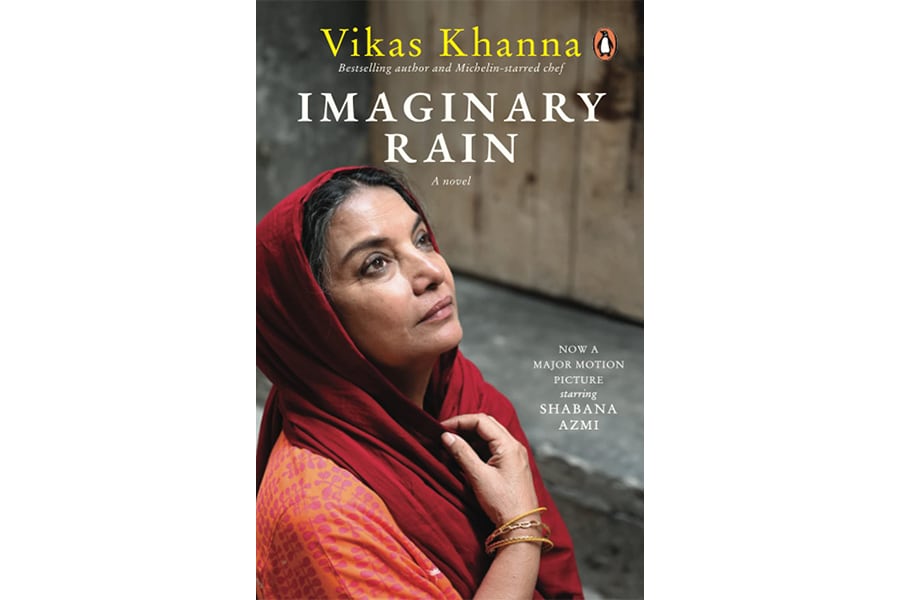

Vikas Khanna is arguably India’s food ambassador to the world. The Michelin-starred chef, who was recently in the news for creating an AI-generated image of Mona Lisa eating Indian food, spoke with Forbes India about the other side of his career—writing books—on the podcast From the Bookshelves. He discussed his most recent work of fiction, Imaginary Rain, which is also being made into a film starring Shabana Azmi.

Khanna says the book is a semi-autobiographical account inspired by his grandmother, who is also one of the reasons he took up cooking. He spoke about why women’s work in the kitchen is often taken for granted, how food is extremely forgiving, and why he wants to use the written word to take stories of Indian kitchens, cuisines and culture to the world. Edited excerpts:

Q. You’ve called Imaginary Rain, which is your 40th book, your best one yet. Why do you think so?

I feel it’s my life’s best work because this is the first time I’ve given a tribute to my grandmom, in a very fictionalised-yet-real way. And when you’re giving a tribute for the first time to someone who is very important in your life, there’s a lot of pressure on you because there is no compromise and you give it your best. I’ve been waiting to tell this story for so many decades. Thanks to the opportunity I got now, I can tell it in such a large scale.