Bengaluru couple go on a philanthropy drive

Photographer-writer duo gave up their homes and jobs to spend their lives living in villages with tribes, to find solutions to their everyday problems

For Piyush Goswami and Akshatha Shetty, Rest of My Family is a way of life, a life-long commitment

For Piyush Goswami and Akshatha Shetty, Rest of My Family is a way of life, a life-long commitment Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

In drought-hit Masrudi village, Latur, farmers have a tough time making ends meet, often sacrificing their children’s education along the way. In Swarupnagar and Baduria, West Bengal, dangerously high levels of arsenic are found in the groundwater, making it difficult to access clean drinking water. In Dima Hasao, Assam, farmers of the mainstay, organic ginger, and other crops are ruthlessly exploited by middlemen.

While their problems are stark and varied, they have a common thread tying them together. They have all been touched by a countrywide philanthropy initiative that believes all humans are part of a larger family—aptly titled Rest of My Family (RoMF).

This isn’t an ordinary philanthropy project. Run by a Bengaluru couple—both engineering graduates—who gave up their homes, corporate jobs and life as they knew it, RoMF for them is a way of life, a life-long commitment. Photographer Piyush Goswami, 33, and writer Akshatha Shetty, 31, have a simple philosophy—to live out of their jeep, drive deep into India’s hinterland, and stay with various tribal communities to process their problems—and drive realistic, implementable solutions and stay with them until they begin to see change. They also run a website with articles and documentaries on these tribes to help raise awareness. They call RoMF a social-work-through-art initiative.

Goswami and Shetty set out on this ‘Drive for Change’ in February 2016, intending to be on the road for a year, raising money via crowdfunding. They returned to Bengaluru almost three years later, in December 2018. With total funds raised to the tune of ₹75 lakh, RoMF has documented and lived with numerous tribal communities in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, West Bengal and Assam. It has also kick-started projects across verticals of education, rural health care, sustainability, sanitation, infrastructure, crafts and livelihood, across these states.

“The seed for Rest of My Family was sown in 2010, when we decided to dedicate our lives to art and philosophy and find ways to bring both disciplines together for socially relevant work. After working in the corporate world, we realised this is not what we wanted to do with our lives,” says Goswami. At this point, Goswami began working on various film and photography projects, while Shetty explored writing as a journalist.

Roughly between 2010 and 2013, they began travelling to rural and tribal communities frequently, sharing their findings through photo-stories. “We did this for a while and thought it would draw attention to the ignored lives of rural and tribal society,” says Shetty. “But over time, we were convinced that documenting alone seldom results in constructive impact on the communities being written about. We knew we had to do more.”

In 2013, Goswami and Shetty gave up their homes and belongings to live a life on the road

“As we travelled and lived with far-flung families and communities, receiving love, care and protection from people who were strangers until that point, we were convinced that all social and cultural walls that separate man from another man, one family from another family, one culture from another culture are a human construct,” adds Goswami. “We realised that everyone we met and lived with was a part of our own family. And, when someone is part of your family, their problems become your problems too. You have to try your best to find a solution to these challenges.”

In 2013, the duo gave up their homes and belongings to live a life on the road and dedicate themselves to that single idea, which forms the philosophy of RoMF. They began with shorter trips, and eventually, set out on the long Drive to Change.

Road less travelled

Through this mega-drive, the couple has documented and initiated help for various causes: Farmer issues in the drought-hit regions of Karnataka and Maharashtra; rehabilitation of Devadasis’ children in Koppal (Karnataka); social issues faced by the Lambani community in Chincholi (Karnataka); the situation of adivasis and the Naxal-state conflict in Bastar, Chhattisgarh; issues faced by the Bonda tribe in Odisha; human trafficking and other challenges near the India-Bangladesh border in West Bengal; and the current situation of the Biate community in Assam.

For instance, in Bastar, inadequate health care infrastructure has led to rampant cases of diseases such as malaria, jaundice and typhoid, as well as deep-seated malnutrition and sickle-cell anaemia. Maternal and infant mortality rates are high. Tribals have to travel long distances to seek treatment; and instead, rely on traditional tribal methods of medicine that may be inappropriate.

In July 2017, RoMF set up a Rural Healthcare Project in the region, which has conducted two medical camps every month since. Shetty and Goswami partnered with doctors Ramchandra and Suneeta Godbole, who had been working long to improve the health of Bastar tribals. However, with limited resources, the doctors were forced to carry out operations with inadequate medical supplies and staff, often resulting in incomplete diagnosis, and therefore, incomplete treatment.

Shetty with children at Dima Hasao, Assam

Shetty with children at Dima Hasao, AssamImage: Piyush Goswami

RoMF, via crowdfunding and with the help of NGO Kara Foundation, raised money for diagnostic devices, kits and resources for quality medical diagnostic facilities in the area. They also helped with administrative support and manpower recruitment. The medical camps are currently active in the Dantewada district; the team comprises two visiting doctors, a laboratory technician and four field assistants.

Similarly, through partners and individual contributors, RoMF has managed to sponsor the education of 400 students across Karnataka, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh and Assam, through a campaign called ‘Vardhana’. One such student is Latur’s Raut Gopal, whose farmer father had no way of paying for his engineering education.

“We visited Latur in 2016, when the region was grappling with consecutive years of drought. Both farmers and agricultural labourers were finding it extremely difficult to make ends meet,” says Shetty. “During our stay in Masrudi, a farmer told us about Raut, a dedicated student who had just finished his diploma in civil engineering and wanted to get a bachelor’s degree, but couldn’t. We saw his spotless academic track record and put a plan in motion to support his passion.”

Now, Gopal is in his final year at college, and has been securing first place every semester. “I had given up the idea of studying further at the time, when Piyush came to see me,” he says. “He saw all my documents and told me not to give up. He saw my house and the way we lived. I’m so thankful... I want to put my degree to good use, become a good citizen and help people, as they have helped me.”

Further east, in Dima Hasao, Assam, RoMF has set up a farmer-producer company to ensure farmers earn fair prices for their organic produce. Called the Kharthong Organic Farmers Producer Company (KOFPO), it was set up in 2018. Ginger is one of the main commercial crops grown in the region, and ordinarily, would fetch farmers between ₹8 and ₹15 per kg. However, with KOFPO behind them, farmers have managed to sell ginger at ₹50 to ₹65 per kg, even driving local middlemen to increase prices this season. For the first time, middlemen are shelling out ₹35 to ₹40 per kilo.

In the red zones of Swarupnagar and Baduria, of the North 24 Parganas district in West Bengal, arsenic poisoning is a serious concern. In 2015, according to NGO Bithari Disha’s water lab analysis, of the 1,407 borewells tested in the area, 49 were contaminated with dangerous levels of arsenic, 178 with iron and 47 with bacteria.

“Our regional NGO partner, Bithari Disha, already had a surface water treatment plant with a 2,000-litre-per-hour capacity. But they only had supply from open water sources (rivers/rivulets) that dry up during certain months and couldn’t be relied on for round-the-year supply,” says Goswami. “We identified that a borewell tapping into ground water would complement the existing facility in dry seasons and provide clean water.”

So in a two-phase project, RoMF first raised funds to dig a borewell and support a water purification and supply project. In the next phase, they worked to expand the infrastructure to increase its capacity and supply 16,200 litres per day. They are on track to make this a self-sufficient project that can raise its own funds; in 17 to 18 months, there should be surplus funds to put projects planned for the future into action.

“On the surface, each community’s challenges seem to be unique and starkly distinct from another. But travelling through various regions has enabled us to connect the dots and find the similarities hidden beneath those differences,” says Shetty. “Whether it is farmers suffering at the hands of exploitative middlemen in Maharashtra, or Gond tribals being exploited by settlers in Bastar; Devadasis and their children dealing with discrimination in Karnataka or minority tribes like Biate being ignored by majority tribes in the Northeast, they are all experiencing the same phenomenon: Exploitation and psychological, economical and physical violence in a society built on selfishness, capitalism and indifference.”

It is interesting to note that no person thinks they are contributing to this injustice, she adds. “Whether it is that middleman in Maharashtra or a settler in Bastar, nobody thinks they are evil. They just address their agenda with a narrow circle of concern and belonging. Clearly, we need a new perspective to analyse the social norms and notions we continue to live by and have held to be non-violent, harmless or peaceful.”

What works for them, they say, is that they do not travel to a region with a ‘Messiah complex’ or with a pre-determined cause they want to take up. “We live with the communities and understand their plight first-hand: Be it walking 1 km to fill water from makeshift tanks to witnessing heartbreaking moments of a grandchild lost to malaria. We immerse ourselves completely into the community,” says Goswami. “Together, we come up with solutions and the villagers are involved at every step. So, it is a huge learning process for both us and the communities.”

“Many years ago, we were in Attappadi, Kerala, with the Moopan or head of the Irula tribe. He told us how a social organisation had built toilets in a few tribal homes,” adds Goswami. “When we asked what it is that they needed the most, he said, ‘Ah yes! You see nobody ever asked us what we want. Our village does not have water. And they built us toilets and left'.”

Obstacle course

A life on the road, especially one that is bumpy, fraught with hurdles and different from the urban life one is used to is difficult. Constant travelling means changing locations, food and water at every stage, making it hard to remain healthy and fit, says the duo. “We watch our food intake closely and try to get enough physical activity,” says Shetty. “When we are in villages we often eat local, drink boiled water and involve ourselves in local sports to stay in shape.”

This can be frustrating, they admit. “We have learnt the hard way that the only thing we have in our control is our attitude and persistent effort. And, no matter how frustrated we were, in retrospect, it seems that everything happened exactly at the right time. It couldn’t and shouldn’t have happened any sooner or later,” says Shetty.

It’s their relentless commitment that sets them apart, says Dubai-based fashion designer Kanchan Kulkarni, who co-founded Kara Foundation with husband Gautam, a real-estate developer. Kara Foundation supports various RoMF initiatives.

“They love doing what they do. This is how they want to live their life. As people who are intrinsically interested in doing something for someone else, they don’t even see it as giving anything up,” she says. “They live in places where most people wouldn’t even imagine travelling to. What we appreciate is that everything has structure and is meticulously documented with stage-wise feedback—it makes you feel involved at every step as a contributor. We know exactly where our money is going.”

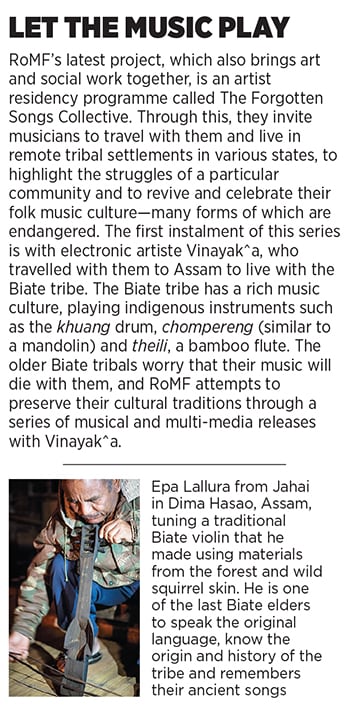

Shetty and Goswami are currently back in Bengaluru, setting up the next phase of RoMF. They hope to create a dedicated team that is based out of the city for operational and administrative purposes, and are in the process of launching a new music-driven project called The Forgotten Songs Collective. Through this, they get a musician to travel with them to tribal areas and highlight their issues and indigenous music in documentary form.

“We have been on the road for almost six years now, driving through forests, deserts and vast rivers. Each human being we have crossed paths with has become part of our family—we focus on building strong relationships with each villager we meet, and that takes time and effort,” says Shetty. “We have spent nights sleeping in the car too—summers are the toughest. Monsoon and winter are delightful. Sometimes, we find ourselves constantly moving out of village homes and hotels, but it is on the road that we feel most at home.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X