Budget 2021 Countdown: Create more jobs to boost economy

The Budget needs to prioritise generating urban employment, getting more women into the workforce, developing industry-oriented skilling, and creating access to and building digital capabilities

A labourer look on Parked bicycles used to transport materials in a wholesale market are pictured in Kolkata ,India ,Sunday August 23,2020.India's unemployment rate is now at a record high of 27.1%, according to the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE).The country has been in lockdown since 25 March to curb Covid-19 infections, causing mass layoffs and heavy job losses.

A labourer look on Parked bicycles used to transport materials in a wholesale market are pictured in Kolkata ,India ,Sunday August 23,2020.India's unemployment rate is now at a record high of 27.1%, according to the Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE).The country has been in lockdown since 25 March to curb Covid-19 infections, causing mass layoffs and heavy job losses.Image: Debajyoti Chakraborty/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The unemployment rate in India stood at 9 percent in December 2020, the highest it had been in six months since the unlocking of the economy in June, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy. This means from the country’s total workforce strength of 427 million, close to 38 million people are without a job.

In the wake of the pandemic, people who lost their jobs and their livelihood mostly included workers in the informal economy, like daily wage or casual labourers, construction workers, drivers/cleaners, gig or temporary workers. An estimated range of 70 to 140 million migrant workers walked back home to their villages as businesses and economic opportunities shut down in cities during the lockdowns. They returned to their villages where a weak winter season of agriculture could not absorb additional workers. With the economy picking up at a slow pace, even those returning to the cities were either unable to find a job or were settling for lower wages.

So, tackling India’s unemployment crisis and creating targeted approaches toward job creation are likely to be huge priority areas in the upcoming Budget.

“What we really need is for the economy to create good, productive jobs. As we saw during the pandemic as well, it is the informal workers that ended up being more vulnerable during the crisis,” says Nalini Gulati, country economist for the India programme of the International Growth Centre. “Jobless growth is simply not sustainable.”

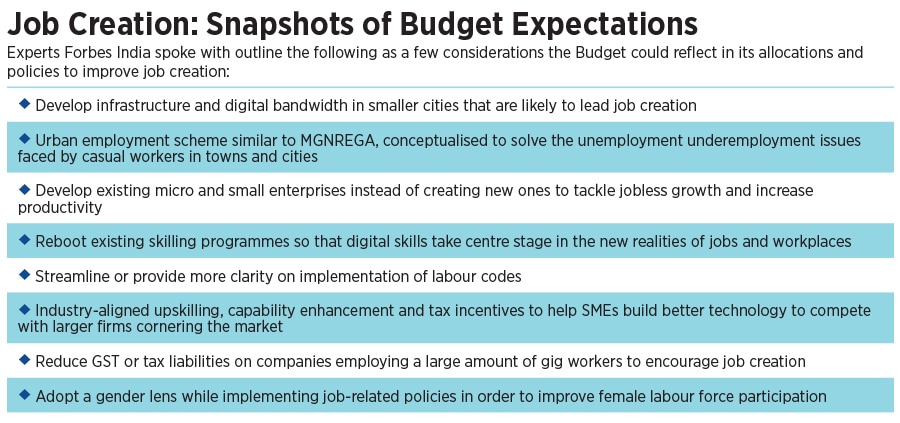

Apart from tax cuts and sector-specific incentives, experts also talk about setting the stage for long-term solutions, including reskilling, access to digitisation, investing in and lifting up existing micro and small enterprises.

Anandroup Ghose, partner, Deloitte India, points out that Covid-19 has changed the structural realities of organisations, jobs and job roles. “While tech is taking away jobs, it also builds new jobs provided there is capability enhancement,” he says. “Globally, there is a concentration of wealth and tech-enabled companies are cornering the market, so small and medium enterprises have to ensure that they have the ability to build or buy the technology, capabilities and skills like these larger organisations.”

Micro and small enterprises hold the key to creating millions of jobs in India, with workers across skill sets and education levels. Close to 110 million workers out of India’s total 427 million workforce are employed in micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). And out of the 63 million enterprises in the MSME sector that employ these people, 62 million are micro and very small enterprises. Experts say that instead of creating new enterprises, it would be advisable to help the existing MSMEs to grow and scale.

A project proposal released on January 23 by Azim Premji University in collaboration with the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) and Tata Institute of Social Science (TISS)-Mumbai, calls for the creation of a Udyog Sahayak Enterprises Network (USENET) project to scale up micro and small enterprises (MSEs) and improve ease of doing business.

The report, currently submitted to the government, proposes an entrepreneurship model, where the Centre enables conditions that will help these enterprises self-sustain and create productive jobs. This includes availability of services like digitalisation and formalisation, ease of availing government loans, subsidies or other benefits, ensuring compliance with local, regional and national regulations, aiding partnerships with digital marketing and payment platforms etc.

Amit Basole, co-author of the report and associate professor of economics, School of Arts and Sciences, Azim Premji University, says that while the 2021 Union Budget cannot introduce the USENET system with its entire scope, it could consider a pilot version of the system. “Given budgetary and fiscal considerations, it could be targeted in a way that more systematic resources are put in place where a bigger difference could be made. For example, the pilot version could be launched in a few select districts or towns or clusters based on Covid-19 impact, where MSMEs have been hurting more etc,” he says.

A pilot, he explains, would also go a long way in establishing how much a network of this nature could help MSEs in getting the confidence to scale and operate a business. The report estimates that on full implementation, the USENET can create an additional 10.3 million jobs over the next five years, going up to 56.9 million jobs by 2031.

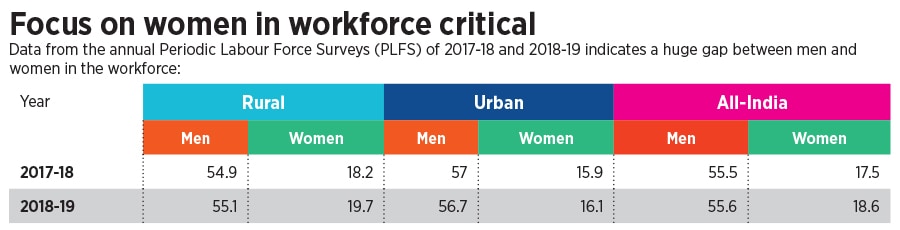

There is particularly a huge potential to grow women-owned enterprises, which are 20 percent of total MSMEs. There are close to 17.6 million women MSME owners, who, Basole says, “face more documented problems in running and scaling up their enterprise than men do”. Overall too, out of the 900 million people who are in the working age group of 15 to 64 years, only 425 million are seeking work and are in the workforce. According to the report, five out of six women are not looking for work.

“Women are getting educated but they choose not to work because they believe that commensurate jobs are not available. So they end up being less willing. Plus there are other issues ranging from cultural restrictions to security and mobility constraints,” says Gulati.

However, she adds that since Covid-19 is changing the way workplaces operate, and making them location-agnostic, a budgetary focus on reskilling and upskilling, and improving digital access could help create more opportunities to improve labour force participation of women. “The government already spends a lot on skilling, but a reboot needs to done, given the new realities of jobs. Digital skills must take centre stage. Access to digital devices also has a gender gap, which needs to be addressed too.”

Ghose of Deloitte India adds that there is no clarity on when people who have migrated away from cities will be back, given that employment-generating sectors like real estate and construction have been slow in picking up pace. So, the smaller towns and cities are likely to take a lead in job creation. “The expectation is that there would be reverse migration as things stabilise and people come back to work in cities. But that may or may not happen soon. If work from home etc continues, people may or may not come back. So Tier II, Tier III cities and beyond, on an average, will have more people, which will lead to a shift in purchasing power,” he says. “The challenge, then, will be to strengthen infrastructure and internet bandwidth in Tier II cities and beyond.”

In this regard, an important consideration that could be made in the Budget is the creation of an urban public job creation programme with an employment guarantee, on the lines of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), says Basole. “But this cannot simply be an extension of the MGNREGA in urban areas and has to be imagined differently,” he says.

For example, Basole explains, seasonal unemployment is prevalent in rural areas but not urban areas. The latter suffers from a constant degree of underemployment among casual and daily wage workers. Urban local governance institutions are much less participatory compared to Panchayati Raj institutions, and “even the scope of public works is different in towns and cities compared to villages”, he says. Whether there is administrative and financial bandwidth to undertake this could be a concern, so Basole suggests that the Budget could also introduce this programme in a pilot or phased manner in certain key districts or towns.

Lack of clarity on the implementation of the labour laws, which spell out the cost of employment and social security of blue-collar workers, is also a concern. “Companies are sceptical about hiring more people right now because of the uncertainty associated with this,” says Pravin Agarwala, co-founder of Betterplace, which connects blue-collar workers to companies, and works with Ola, Flipkart, Ecom Express, Swiggy, Zomato and Dunzo, among other organisations.

He adds that it would be good if the Budget provides more clarity on the impact the labour codes will have on companies hiring gig workers, apart from providing tax benefits or GST reduction for enterprises that help create these jobs. “There are different tax slab compositions for us based on manpower [hired] and supply, which could be 10 percent or even 18 percent. Bringing that down and incentivising every job that companies help create will be helpful.”