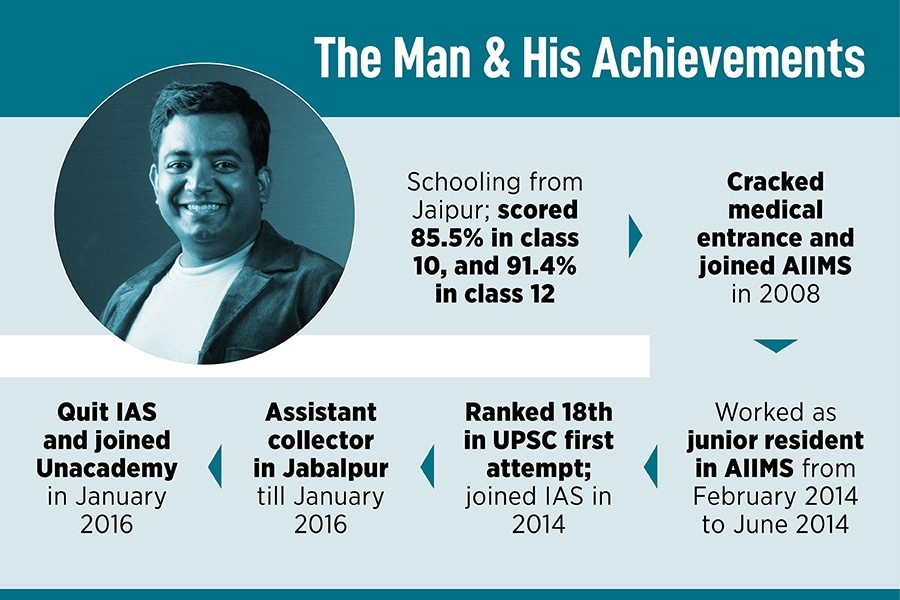

Unacademy's Gaurav Munjal is ready to drink the polyjuice potion. Can Professor Snape transfigure into Professor McGonagall?

Stung by allegations of rampant 'toxic' culture, stirred by a pressing need to become more humane and goaded by an impending funding winter, Gaurav Munjal is trying to rewire himself and Unacademy. Can the livewire make India's biggest online test prep platform unlearn and learn?

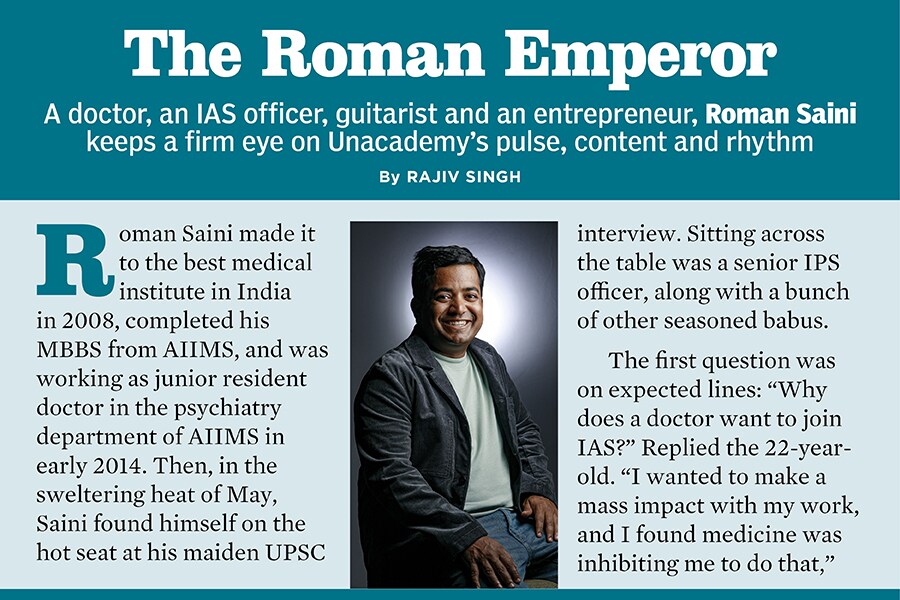

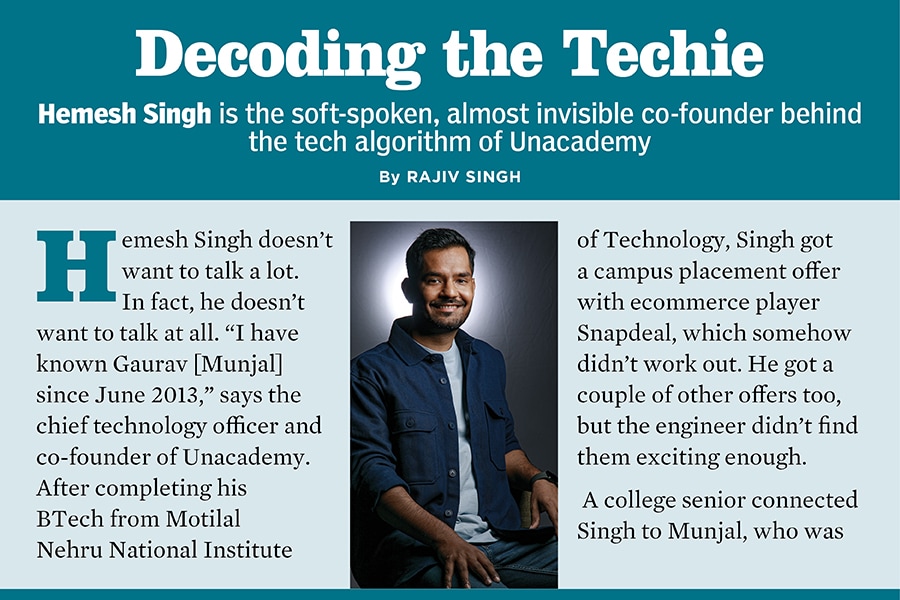

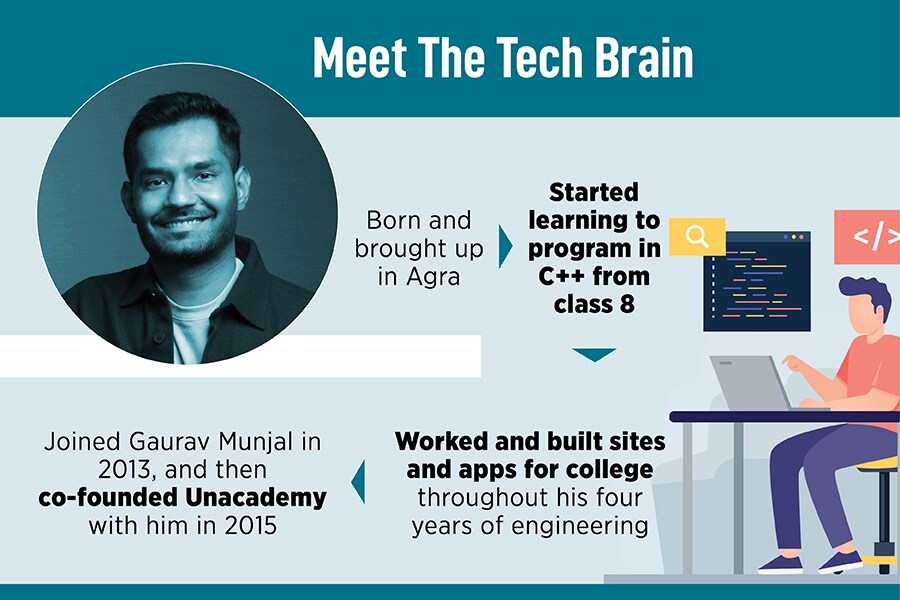

(From left) Roman Saini, Gaurav Munjal and Hemesh Singh, co-founders of Unacademy Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

(From left) Roman Saini, Gaurav Munjal and Hemesh Singh, co-founders of Unacademy Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

“Is it jetlag? Why is my mind going numb? Am I dreaming?” an inquisitive Gaurav Munjal wondered after a spate of whirlwind meetings. “I was just absorbing and writing. I was not reacting,” recalls the co-founder and chief executive officer of Unacademy who was in New York with friend Roman Saini. It was a gruelling week. The co-founders of India’s biggest online test prep platform had pitched to over a dozen hedge funds for their next round of funding over six days, and they were exhausted. To make matters worse, a bunch of deep-pocketed funders, who were more than keen to meet the founders just a few months ago, played truant. “It was shocking. They were the ones chasing us and now they disappeared,” says Munjal.

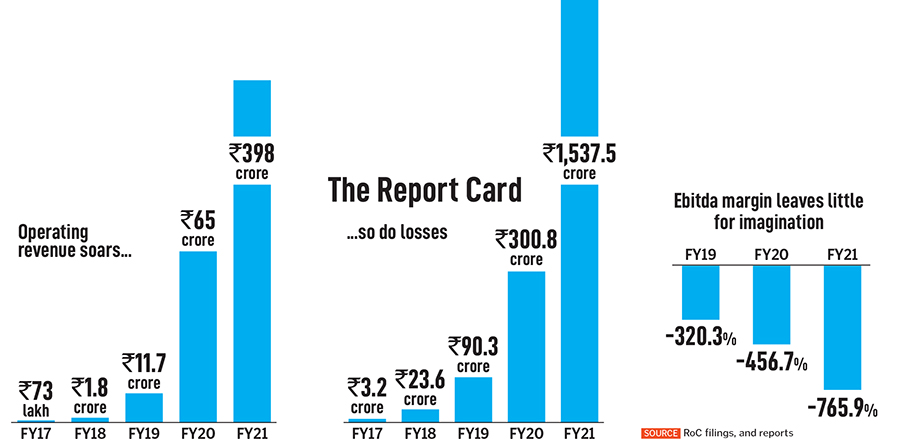

Three years ago, in 2019, a VC in India was pushing his luck with the maverick founder. “In just one fiscal, your losses have zoomed from ₹90 crore in FY19 to ₹300 crore in FY20,” he sternly conveyed the message, underlining the ₹3.22 crore losses Unacademy posted in FY17. “I know my maths,” Munjal curtly replied. “I will either go big or go home,” he retorted aggressively and nipped the conversation. “He was in no mood to listen,” says the VC, requesting not to be named. “Hyper ambitious founders don’t like to be counselled,” he says. In June 2019, Unacademy raised $50 million in its Series D round of funding from a battery of backers such as Steadview Capital, Sequoia India, Nexus Venture Partners and Blume Ventures.

High on a funding steroid, Munjal was in no mood to slow down. And he was probably playing the right game. 2019 was a different era, and the markets were rewarding aggressive growth. The only talking point was how much can one grow. From a hefty 50 percent year-on-year growth to an ambitious 100 percent and even an unrealistic 200 percent was what entrepreneurs would aim at, and VCs would lustily cheer from the sidelines, egging the founders to sprint at a lightning pace. The VCs rooted for the best magician who could travel at supersonic speed akin to Harry Potter’s broomsticks. Munjal was one of the magicians. “I believe technology is magic. The best products are magic. Look at Tesla; it’s magic,” he says.

Meanwhile, in New York this May, there were clear signs that the magic show was about to end. “Pehle profitability dekho, thoda bahut growth kar dena (First look at profitability and then think of modest growth),” advised one of the Indian VCs working with a global fund. Curious, Munjal asked a follow-up question. “Can you quantify thoda bahut?” he asked with a broad smirk. The investor smiled. “It means 5 percent or 10 percent,” he said. “I’m like seriously? I was shocked,” Munjal recalls. The second set of dos was even more interesting: Focus on unit economics and free cash flows.

These words—unit economics, cash flow, profitability, conserving cash—were not only alien but also the world in which VCs were using such terminologies looked like a different planet. “Such words were alien since I started Flat.to in 2013,” says Munjal, who co-founded the real estate platform for college students and bachelors—which was acquired by CommonFloor.com in April 2014. “We have had a 14-year bull run,” says Munjal, who was about to hear a horror story from another VC. At the peak of the dotcom bust in 2000, the funder pointed out, parking garages went empty. “It freaked me out,” he recalls.

Speed, culture and long Hours

Back home in India, for the first few years since co-founding Unacademy in 2015 along with Roman Saini and Hemesh Singh, it was time for a section of employees to freak out. The reasons were many. First, they were struggling to strike a work-life balance due to excessive long working hours. “I quit because I couldn’t get the time to do any other thing,” says one of the employees who left the edtech startup in 2018. “There was too much work.” Back in September 2016, in one of his blogs, Munjal gave a peep into the life in a startup. In early-stage startups, he wrote, you work six to seven days a week. “Personal life takes a hit, you don’t have time to even call your parents, forget anything else,” he maintained.

Two years later, in December 2018, a few months after the above-mentioned employee and many more quit, Munjal posted another blog. This time the message was to convey why the edtech startup is not a place for everybody. “I have always believed that the speed at which we operate is not everyone’s cup of tea,” he wrote. Either the people who join Unacademy, he underlined, stay for 10 days or 10 years. “Either they get so overwhelmed with speed, execution and intolerance towards mediocrity that they leave in 10 days,” he penned.

There were other reasons, too, for the heartburn among the staff. Munjal’s deep obsession with the quality of work meant less tolerance towards mediocre work and staff. “Whether it’s during the hiring process or it’s during the performance reviews or it’s letting someone go, we will not tolerate mediocrity at any cost,” he underlined in his blog. The first few years, the co-founder stayed true to his hardcore beliefs, and honest but brutal assessment—at times bordering on insult—became the norm. Munjal explains his mindset during the formative years. “I was a young kid who had no revenue for the first four years,” he says. The message was either deliver or leave. “Some people don’t like that much honesty. They can’t hear that their work is mediocre, and they can’t take blunt candid feedback,” he reckons. For a long period, he points out, his Twitter bio was ‘Mediocre teams don’t build great companies’. “I still believe that mediocre teams don’t build great companies,” he says.

The issues snowballed and people started talking about the alleged toxic work culture. The allegations were a cultural shock for Munjal who was always used to a hard work life. A few years ago, he listed out his top learnings as an entrepreneur. A few of the dos and don’ts daringly stand out. “If you can’t give 14 to 16 hours a day, don’t startup,” was the first. If criticism bothers you to the point that you can’t take it, don’t startup. The third hits the bull’s eye. If you have a moral obligation to be nice to people working with you even when they are not doing their job properly, and you must tell them bluntly, don’t startup. As an entrepreneur, Munjal saw no wrong in his strict approach.

His detractors, though, maintain that the environment is demoralising. They point to the chilling manner in which he shut down the K12 business at the end of last year, which reportedly resulted in job loss for over 1,000 people. Munjal, however, defends the move. “Nobody likes layoffs. But we have to make the company survive,” he says. “We need to ensure that the company doesn’t die,” he adds, underlining the uncertain nature of the startup ecosystem and the need to take hard calls. In one of his earlier blogs, he portrayed the picture of the stressful side of a startup life. “You’re insecure, you don’t know what will happen next. You’re not relaxed,” he wrote, justifying why this flux state of mind is not a bad thing. “It somehow pushes you to your limits. Remember, Batman could only climb the prison when he climbed without the rope,” he mentioned.

Fast forward to June 2022. Munjal has started to realise that there is no Batman without Gotham. A virtual meeting with Reed Hastings, the co-founder of Netflix, in November 2020 drove home the point that Batman needs Gotham and its citizens. Hastings made Munjal understand that if the job of the employees is to help grow the company, the founder’s job is to help the staff achieve their goals. “They too have life goals. And their life goals cannot just be about Unacademy,” says Munjal, who has been trying to rewire himself over the last year or so. “I wouldn’t call our culture toxic.”

Also read: I fear failure a lot. A lot: Gaurav Munjal

He explains what went wrong. Till 2019, Unacademy didn’t have a business model. “So nobody focussed particularly on culture,” he says. Though the edtech startup focussed on diversity, nobody defined culture in the form of a playbook. “There was only one culture, and it was of winning. Hamein jitna hai (We have to win),” he says. The rules of winning, though, were clearly laid out: No mis-selling, not making sub-standard products and winning through strategy. “I have not had a loud debate with most people in my leadership over the last one year,” he claims. “Every quarter, every month we are getting better.”

Munjal’s focus now is on building the right culture. “I wake up and read top five priorities every day. Culture is one of them,” he adds. He has also stopped being ruthless in sharing feedback. At times, the feedback was so brutal that it had a negative impact. “Now, I don’t do that,” he says. The objective now is to inspire people. “I don’t want the person to feel bad,” he says. The magic, he reckons, lies in inspiring the person and getting the best out of them.

Witches, wizards, and Harry Potter

The magic, though, is not confined to the transformation that Munjal is seeking by trying to reinvent himself. It’s in the air across the two expansive floors of the multi-storeyed building in Bengaluru which houses the corporate headquarters of Unacademy. In fact, it starts from Munjal’s den on the fifth floor. There is a stuffed Hedwig—Harry Potter’s pet snowy owl—silently perched on a cushy, bright yellow sofa at one of the corners of the room. In the middle, there is a long cylindrical table which has a huge computer screen fixed at one end. Apart from a mobile charger and ear plug, there is a small box of ‘Tiger Balm’.Next to the table is a vertical book rack loaded with over two dozen books. From Hard Landing, Blitzscaling, BeastieBoys and Narconomics to No Rules Rules, No Shortcuts and The Courage to be Disliked, authors and genres of all kind find a place of honour. Then there is a photo frame with a quote from Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince placed in the other corner of the room. “And now, Harry, let us step out into the night and pursue that flighty temptress, adventure,” it reads.

It’s indeed night. In fact, it’s late night as an hour-long meeting, which started sharp at 9.30 pm, gets extended to another hour on a breezy Wednesday night. It has been a long day for Munjal, and over two dozen employees who are still working. A signboard stationed outside the fifth floor reminds one of the official working hours. “Office timings are restricted from 10 am to 7 pm,” it reads. Halfway into the meeting, he orders a cup of coffee and some bhujia. “I had an early dinner,” he says, as the man from Jaipur, Rajasthan, munches on namkeen and continues with the conversation. “Harry Potter had a huge role in how I think and how I have grown up,” he confesses.

It’s indeed night. In fact, it’s late night as an hour-long meeting, which started sharp at 9.30 pm, gets extended to another hour on a breezy Wednesday night. It has been a long day for Munjal, and over two dozen employees who are still working. A signboard stationed outside the fifth floor reminds one of the official working hours. “Office timings are restricted from 10 am to 7 pm,” it reads. Halfway into the meeting, he orders a cup of coffee and some bhujia. “I had an early dinner,” he says, as the man from Jaipur, Rajasthan, munches on namkeen and continues with the conversation. “Harry Potter had a huge role in how I think and how I have grown up,” he confesses.

Munjal’s obsession with Harry Potter gets reflected in the name of his registered company. “It’s called Sorting Hat Technologies,” he smiles. The Sorting Hat, he explains, sorts new students of Hogwarts, the school of wizardry in the Harry Potter series, into four houses. “JK Rowling hasn’t sued us yet,” he laughs. On the third floor, he points, the cabins are named after Harry Potter. The third floor indeed takes you into the world of Witches and Wizards. The women’s washroom is labelled as ‘witches’ and the male room gets the name of ‘wizards’. The cabins are named ‘The Burrow’, ‘Riddle’, ‘Manor’, ‘Hagrid’s Hut’, and ‘Malfoy Manor’. There are inspirational quotes hung from the ceiling and plastered on huge pillars. There is one which catches your eye—Learn and unlearn.

In May this year, Munjal had his learning session. The VCs he met in New York made him see the writing on the wall. The founder who cared more about the top line even as the bottom line plummeted over the last five fiscals since FY17—₹3.22 crore, ₹23.58 crore, ₹90.27 crore, ₹300.8 crore, ₹1,537.5 crore—was quick to take the crash course, display a sense of urgency in fixing the unit economics which had gone haywire, and spread the message to the organisation.

After coming back to Bengaluru, he shot an internal email to employees pressing upon the urgent need to save every penny and scout for elusive profitability. “I don’t remember a time where Unacademy was ever resource-constrained,” he wrote in the email. The company, he added, always raised more money than what was needed. “This allowed us to continuously experiment and grow without worrying about when we will run out of money,” he said candidly admitting that the company flourished in an environment where resources and capital were abundant. “But now we must change our ways… Winter is here… we must survive the winter,” he added.

Winter, survival instinct, and paranoia

Back in 2014, Munjal couldn’t survive the winter. “I ran out of money in my first startup,” he recalls. Flat.to was bought by Commonfloor. “So I know what it is like when you run out of cash,” he says. A year later, when Munjal co-founded Unacademy, the second-time founder decided not to repeat the mistake. “I swore to myself that, any point in time, Unacademy will have a runway of four years,” he says. The failure to cling on to his maiden venture also instilled a sense of paranoia in him. “I fear failure a lot. A lot,” he says (see interview). “I am so afraid of failing that I’m in a perpetual paranoia.”The fear of failure changed the way Munjal approached maths. “For me, 18 is 0,” he says, explaining his weird logic. If 18 months of money is left in the bank, then it is presumed to be zero money. In 2018, he came very close to the zero mark. There was a month of runway left—which means 19 months—and Munjal had pitched to 18 investors. “All of them rejected… 18 f******g pitches rejected,” he says. “One must never run out of money,” he reiterates. The fear of failing also led to the habit of fast course correction at all costs. Take, for instance, the decision to exit from the K12 business late last year. The move resulted in large layoffs—some reports put it to over 1,000.

Munjal says the ‘surgery’ was necessitated by two things. First, a realisation that the business model of one-to-one tuition is flawed and it won’t make money. “Entering K12 was more out of FOMO (fear of missing out),” he accepts. So was it a mistake or a blunder? “It was somewhere in between,” he quips. “We still lost a few millions. But we got off the poker table early.” Unacademy also lost employees. “Nobody likes layoffs. But we need to ensure that the company doesn’t die,” he says. The survival instinct dominated all other instincts.

So, does he have enough food and fire to survive the winter? “Four years,” he claims. Unacademy, he lets on, is well-capitalised and has money in the bank for another four years. If that’s the case, what was the need to go to New York? Some of the funds, he contends, were interested to invest, and talks were in the final stages. “We will raise a round towards the end of July-August,” he says. The valuation, though, would be ‘realistic’. For a startup that saw its valuation soar—$4 million, $110 million, $229 million, $465 million, $1.3 billion, $3.44 billion from 2015 to 2021—the word ‘realistic’ again sounds alien. “This time we have a reasonable expectation. The valuation would be slightly more than the previous round,” says Munjal.

But can he bring down the staggering losses? “In FY22, we will still have losses, but they would come down drastically,” he claims, declining to share the financials. By FY23, he avers, the test prep business will be fully profitable. The startup has made its sales more efficient, has cut brand marketing and advertising spend, focusing a lot on organic growth channels, has closed all experiments and is solely focusing on test prep, Relevel and Graphy. “So unit economics will improve a lot. Ebitda margins will improve by 2x to 2.5x,” he claims.

But can he bring down the staggering losses? “In FY22, we will still have losses, but they would come down drastically,” he claims, declining to share the financials. By FY23, he avers, the test prep business will be fully profitable. The startup has made its sales more efficient, has cut brand marketing and advertising spend, focusing a lot on organic growth channels, has closed all experiments and is solely focusing on test prep, Relevel and Graphy. “So unit economics will improve a lot. Ebitda margins will improve by 2x to 2.5x,” he claims.

While his backers love the new sense of pragmatism and urgency to get the company in shape, they also applaud the fact that Munjal has not blunted his edginess. “Gaurav is somebody who just moves fast and breaks things fast,” says Sameer Brij Verma, managing director at Nexus Venture Partners, which was the first—and is the largest shareholder—institutional investor in Unacademy. “If it works, he scales. If it doesn’t, then he’s also happy to admit his mistakes and move on,” he says.

This is the guy, Verma stresses, who is ready to be unpopular for doing the right things. The fund, he adds, backed him for his edginess, thought process on product, ambition, and understanding of how consumer internet psychology works. “He has crazy unbridled ambition,” he says.

During the fag end of 2016, Verma got a first-hand experience of Munjal’s ‘crazy’ side. The meeting took place at a café in Bengaluru. Unacademy had managed to get some seed funding and Munjal was looking for his first institutional backer. Verma asked Munjal to talk about his vision and the edtech startup. The founder, interestingly, flipped the tables. “Why don’t you talk about your fund? Why should we take money from you?” he asked. Who asks such a question from a VC? “That’s Gaurav for you,” Verma smiles, adding that entrepreneurs must also get to know their investors. “Very competent founders always ask this question,” he says, adding that Munjal has matured a lot over the years. “He’s learning all the time.”

Munjal, too, believes that he asked the right question. “The question didn’t come out of arrogance,” he says. A VC-founder relationship, he underlines, must not be like a master-slave one. “It should be like peers. We should be partners,” he says. One must build a strong rapport with the investors who are backing you. “I’m so glad to have people like Shailendra Singh (Sequoia) and Sameer (Nexus). They’re like co-founders, and I have long debates with them,” he says.

Another learning has been to respect rivals. “At one point, he wanted to kill us,” says one of the edtech founders requesting anonymity. Unacademy wanted to buy out the smaller competitor, the founder declined and Munjal didn’t take the rejection kindly. Teachers were poached at astronomical packages. “The idea was to bleed us with a thousand cuts,” he says. Things, though, have changed over the last few months. “He is still aggressive, but is not vindictive,” says the founder who still gets sporadic messages from Munjal. But the messages now are friendly in nature.

Back in Bengaluru, Munjal contends that he is reading, learning, and unlearning at a fast pace. “I am building a sports team, and it can’t be toxic,” he says. There will be place for performers, there will be ample opportunities for the ones who need to improve, but mediocrity still won’t be tolerated. Long working hours can’t be compromised. The biggest difference between the past and present, Munjal explains, is that the startup makes it culture crystal clear during the hiring process. “We say this is the culture. And it’s tough,” he says. But is he proud of everything that he has done? “No,” comes another candid reply. “Could he have been more empathetic?” “Yes. I’m learning,” he smiles looking at his friend Hedwig.