Authors give legends a contemporary twist

Mythological tales are in vogue - some new, some retold

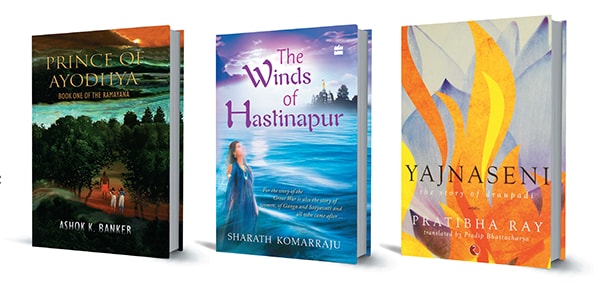

Anyone who closely follows indian publishing would have noted a few years ago that retellings of mythological tales were becoming a sub-genre of contemporary fiction. Well, matters have progressed apace and it is now observed, particularly in more cynical quarters, that such books are a cottage industry unto themselves. The last time I went to a bookstore—you know, the physical kind that some of us still trudge to like museum-goers—I saw an entire shelf packed with titles that read “The Mahabharata Quest”, “The Ramayana Code”, “Draupadi in High Heels” and such. And that was only the “new popular fiction” section—it didn’t include older titles such as the multi-volume, fantasy-style renderings by Ashok Banker, beginning with Prince of Ayodhya, or the English translations of acclaimed regional language books such as SL Bhyrappa’s Parva, Pratibha Ray’s Yagnaseni or MT Vasudevan Nair’s Randaamoozham.

No doubt many of the new books are lazy attempts to cash in on the popularity of pre-existing stories by making a few superficial changes and repackaging them—or even creating hybrids that hope to replicate the success of Western thrillers like The Da Vinci Code. Yet amidst the dross there are also a few genuine efforts to re-examine conventional perspectives and deal with less well-known subplots. Sharath Komarraju’s The Winds of Hastinapur, for instance, doesn’t try to capitalise on the Mahabharata’s most popular episodes; instead, the author directs his imagination and empathy at the epic’s early passages, which many casual readers aren’t familiar with—the childhood of Ganga and Shantanu’s son Prince Devavrata (later to be known as Bheeshma), the tangle of succession issues that results from his oath of celibacy, and his stepmother Satyavati’s desperate efforts to keep the throne of Hastinapura secure.

Equally notable is the anthology Breaking the Bow, which collects speculative fiction inspired by the Ramayana. Editors Vandana Singh and Anil Menon were clear about their brief for the collection: They didn’t want wholesale retellings but tales that elaborated on the known elements of the mythological universe. For this reason, they even politely rejected a story by Manjula Padmanabhan, set in the future with all the characters gender-reversed: Rama as Rashmi, Lakshman as Lakshmi, Sita as Sidhangshu. (Padmanabhan subsequently did another story for the collection, centred on Ravana’s wife Mandodari.) As often with anthologies, the result is a little uneven, but includes many fine pieces such as Aishwarya Subramanian’s “Making”.

Here, the main story is told in short vignettes and always from a slightly unsettling, off-kilter viewpoint, with creation and destruction (or making and unmaking) being the running themes. The characters are addressed by their more obscure names—Mythili for Sita, Meenakshi for Surpanakha—and Rama’s divinity, though accepted, is not celebrated as something life-affirming; this is a moody, megalomaniacal God. (“He must act out these petty human performances, as if he could not merely think different circumstances into existence. So he performs rage, and standing on the edge of a sea he could part with a mere flick of his hand sends mortal creatures to do his work instead.”

If many retellings search for nuance by lending a sympathetic ear to the nominal “bad guys”—to overturn the “history as written by the victors” narrative—Anand Neelakantan’s patchy but often provocative Ajaya: Epic of the Kaurava Clan goes to the extreme of turning the envious Kaurava Duryodhana into a thoughtful, sympathetic hero (who has the support and friendship of many high-minded characters such as Balarama and Ashwathama) and the Pandavas into the antagonists—not villains exactly, but buffoons who don’t deserve the sympathy they get, and who are too easily made puppets by their cousin Krishna “who believes he has come to this world to save it from evil”. (Note what a difference the inclusion of that “believes” makes to the sentence! Such little touches are vital to these storytelling departures.)

Other books fulfil a vicarious need for readers who are a little tired of the versions of the stories they first heard from their grandparents decades earlier. “I have always been so curious about Urmila’s story,” my wife once told me, expressing sympathy for Lakshmana’s wife, one of Ramayana’s most peripheral characters, who stays behind in the palace while her husband goes (voluntarily) into exile with his elder brother Rama. Now, Kavita Kane’s Sita’s Sister fills this gap. Kane’s earlier book The Outcast’s Queen drew on the perspective of a marginal character in the Mahabharata (and was somewhat derivative of Shivaji Sawant’s great Marathi novel Mrityunjaya) but the demands on Sita’s Sister are a little trickier since Urmila is so removed from the main action of the epic involving Rama, Lakshmana and Sita’s adventures in the forest. Kane gets around this by mostly dwelling on incidents before the exile—from Sita’s swayamvara to Urmila’s finding out about the plot against Rama, and her sorrow that her husband has chosen to play bodyguard rather than stay by her side. In the process, the Urmila she creates is a strikingly (and perhaps anachronistically) modern woman with a mind of her own, frequently set up in opposition to her sister Sita who comes off looking rather subservient in comparison.

For another tale, from another culture, about a woman sitting at home hearing stories about her hero-husband’s exploits, see Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, which was published as part of Canongate’s myth series. Atwood tells The Odyssey in the voice of Odysseus’s wife Penelope, waiting for him to return from his adventures across the sea, and there is much tongue-in-cheek demythologising, as in the conflicting reports about Odysseus’s battle with a giant one-eyed Cyclops (it was only a one-eyed tavern-keeper, someone says, and they were squabbling over the bill). Meanwhile Penelope’s 12 maids, destined to be hanged, pop up with Gilbert & Sullivan-like ditties in between the narrative (“We are the maids / The ones you killed / The ones you failed / We danced in air / Our bare feet twitched/ It was not fair”), which means that opposing tones—high drama, slapstick comedy— are mixed together in a way that does justice to the idiom of ancient literature.

A quieter, more psychologically realist style is employed by the Irish writer Colm Tóibín in The Testament of Mary, which revisits another distant, mist-shrouded story. Jesus Christ’s mother, the Virgin Mary, is the narrator here, and we first see her as a confused old woman in need of care, being visited by apostles who want to greedily collect all the information they can about her dead son, to begin the process of deifying him. But Mary resists this. She doesn’t care about the big picture and she doesn’t see herself as being divinely ordained to produce the Messiah—her plaintive voice is of a woman who yearns for a return to the days when she and her child and husband were happy together, untouched by such lofty responsibilities. Like most of the other books mentioned here, this intense narrative—marked by the urgent need to remember as well as the pain of remembering—places the human element before the grand, mythic one.

The author is a Delhi-based writer and journalist

(This story appears in the Mar-Apr 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)