Tushar Mittal: Journey from an enterprising boy to an insatiable entrepreneur

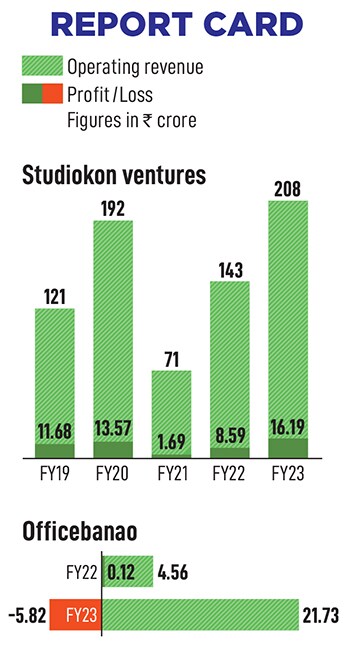

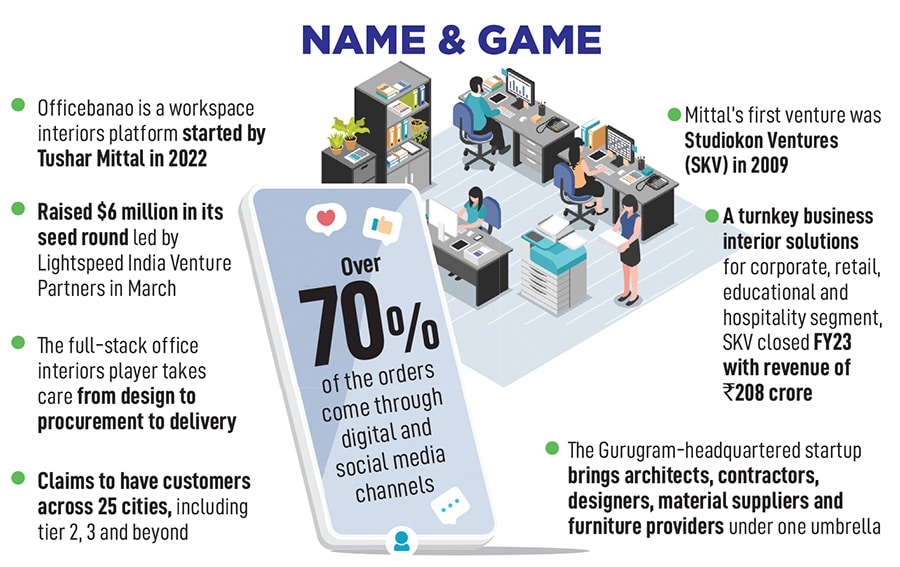

A village boy from Rajasthan fights formidable odds and manages to turn the tables on adversity with his bootstrapped venture Studiokon Ventures (SKV). Can Tushar Mittal now get a seat at the table with his VC-backed Officebanao?

Tushar Mittal, founder and CEO of Officebanao

Image: Amit Verma

Tushar Mittal, founder and CEO of Officebanao

Image: Amit Verma

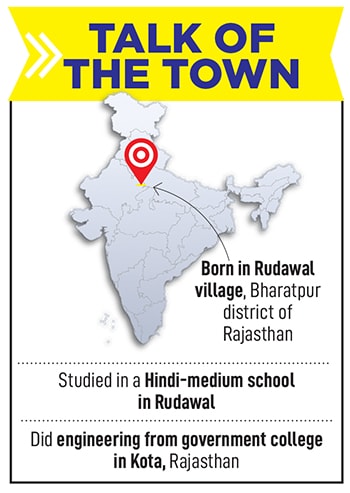

A young Mittal gave in to his duty, and unpacked his bag. Though he was aware of the monthly ritual—and also the fact that there was some element of truth in what his father uttered about the quality of education in the school—he eagerly looked forward to his daily learning. The fact that he had to walk a few kilometres every day to attend the government school was never a deterrent. The fact that most of the time the teachers used to bunk their classes never dampened the enthusiasm of the young learner. And the fact that even English used to be taught in Hindi was not a bummer for Mittal. “My uncle always used to tell me that I can change my destiny through studies,” recalls Mittal, who ran away from his home after finishing senior secondary. Reason: He wanted to study.

A little help from his relatives landed him at a coaching institute in Kota. The father relented, took an education loan from a PSU bank, and the rebel boy started preparing for the engineering entrance. He failed in his first attempt to clear IIT, and lack of financial resources preempted any move to continue with his studies for another year. “I got admission in a government engineering college in Kota,” says Mittal, who opted for civil engineering. To make ends meet, he started working with local contractors on a part-time basis and also ran a canteen in Kota. This was, however, not the first time that the young boy was exhibiting his enterprising side. During his school days, he used to borrow money from his father, buy comics from the nearest town, and then rent them to his friends. “I even bought a cycle, and gave it to my friends on rent,” he recounts.

A little help from his relatives landed him at a coaching institute in Kota. The father relented, took an education loan from a PSU bank, and the rebel boy started preparing for the engineering entrance. He failed in his first attempt to clear IIT, and lack of financial resources preempted any move to continue with his studies for another year. “I got admission in a government engineering college in Kota,” says Mittal, who opted for civil engineering. To make ends meet, he started working with local contractors on a part-time basis and also ran a canteen in Kota. This was, however, not the first time that the young boy was exhibiting his enterprising side. During his school days, he used to borrow money from his father, buy comics from the nearest town, and then rent them to his friends. “I even bought a cycle, and gave it to my friends on rent,” he recounts.

A few years later, in 2005, Mittal didn’t have any money to pay rent when he landed in Delhi. After finishing engineering, he wanted to join National Institute of Construction Management and Research (NICMAR).

The trigger was his three-month internship at a big, multinational construction company during his college stint. Mittal noticed that the engineers who were armed with a degree from NICMAR had an edge over others in salaries as well as professional stature. He borrowed money from his friends and relatives, came to Delhi and stayed at Nizamuddin Railway station for a few days.

After the professional course, Mittal discovered another bitter reality. Though a campus placement landed him a job at DLF, he didn’t stand a chance among his peers who came from hallowed institutions, had a privileged background and flaunted their fluency in English. “They got laptops and desk jobs, and I was made to run in the fields,” rues the civil engineer who struggled with his communication skills. “I thought that the language barrier in the city will never let a village boy shine,” he says. “I felt dejected.”