Chalo: Building mobility for tier 2 and beyond

A short by-chance stint in Bhopal prompted cofounder and CEO Mohit Dubey to ditch his American dream to build solutions for rural India. Now, he's disrupting rural mobility

Chalo co-founders: (From left) Dhruv Chopra, Mohit Dubey, Priya Singh and Vinayak Bhavnani

Chalo co-founders: (From left) Dhruv Chopra, Mohit Dubey, Priya Singh and Vinayak Bhavnani

Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

Mohit Dubey had a change of heart in Bhopal. The young software programmer from Mumbai, who just got his prized US visa, decided to spend three months with his in-laws in Bhopal before joining his overseas job. Dubey started working at a small company in the capital city of Madhya Pradesh—known as the Heart of India—which provided citizen-centric services to villagers such as getting a birth certificate and a copy of land records. During one of his visits to a remote village, he discovered a shocking side of the countryside: People didn’t have access to doctors; one had to wait for hours to get a bus; and many died because they couldn’t reach the city hospitals on time.

Dubey dumped his US dream. “Dying due to lack of health care access is outrageous and not acceptable,” he says. The software programmer decided to take a stab at telemedicine to solve rural India’s woes. The idea was to connect distant villages with district hospitals. The problem, though, was that very few believed in his idea. For three years, Dubey made futile attempts to convince government officials and politicians, but to little avail. His telemedicine venture did not got a green light.

Two years later, Dubey, along with three co-founders, started CarWale, an automotive classified portal in 2005. The idea was to solve the mobility needs of urban India. Five years later, after scaling the venture—it was among the top three players; the others being CarDekho and CarTrade—Dubey sold it to German media conglomerate Axel Springer, one of the largest multimedia companies in Europe which picked up a 52.1 percent stake. Another 18.3 percent was bought by the India Today Group. “The offer was too tempting to resist,” he recalls, declining to share the deal size. There was another reason to sell out. The first-time entrepreneur wanted to expand his maiden venture abroad. A big European partner with deep pockets, he thought, was best suited to make CarWale live its global dream.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

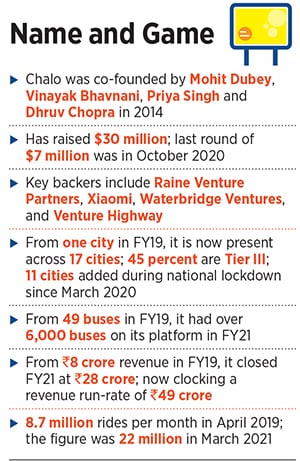

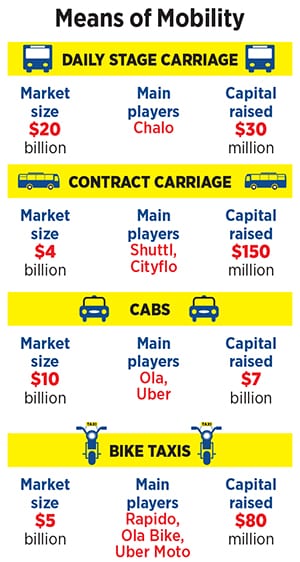

The bus segment, he reckoned, was not only six times as large as the entire taxi segment, but it also presented a $20 billion opportunity.

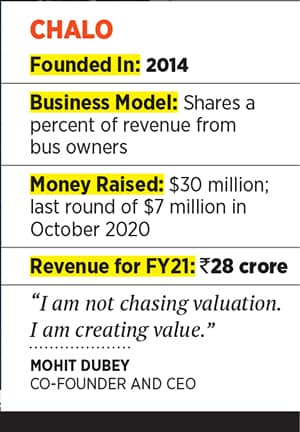

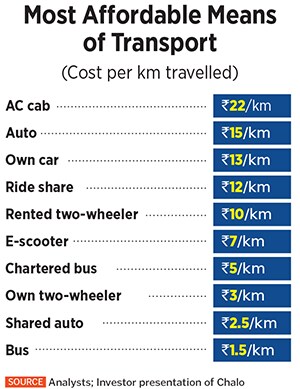

The bus segment, he reckoned, was not only six times as large as the entire taxi segment, but it also presented a $20 billion opportunity.  Cut to March 2021. Chalo posted ₹28 crore revenue in FY21, and is now clocking a run-rate of ₹49 crore. It has over 6,000 buses on its platform across places such as Meerut, Mathura and Prayagraj in Uttar Pradesh; Shimoga, Udupi and Hubli in Karnataka; and Jabalpur, Sagar and Indore in Madhya Pradesh. Chalo counts WaterBridge Ventures, Raine Venture Partners and Xiaomi among its backers. “Our mission is to solve the daily commute for masses,” says Dubey. While in big cities, buses serve as one more mode of transport, in Bharat, they are intrinsic to mobility. “Buses are the heart of transportation for smaller towns and villages,” he says.

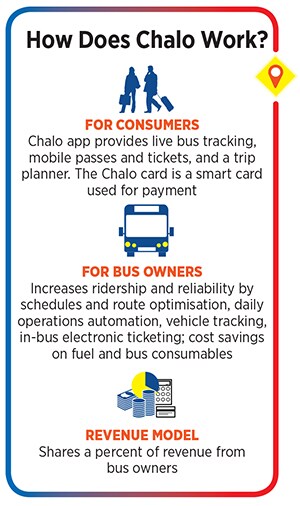

Cut to March 2021. Chalo posted ₹28 crore revenue in FY21, and is now clocking a run-rate of ₹49 crore. It has over 6,000 buses on its platform across places such as Meerut, Mathura and Prayagraj in Uttar Pradesh; Shimoga, Udupi and Hubli in Karnataka; and Jabalpur, Sagar and Indore in Madhya Pradesh. Chalo counts WaterBridge Ventures, Raine Venture Partners and Xiaomi among its backers. “Our mission is to solve the daily commute for masses,” says Dubey. While in big cities, buses serve as one more mode of transport, in Bharat, they are intrinsic to mobility. “Buses are the heart of transportation for smaller towns and villages,” he says.  Dubey dangled a bait: Guarantee money. The business proposition for bus operators in Bhopal was simple: The daily revenue of buses—whatever it was—was paid by Chalo every day in the morning. In return, Chalo took care of automation of daily operations, vehicle tracking, in-bus electronic ticketing, bus consumables and cost savings on fuel. The idea was to increase ridership and reliability by scheduling buses on time and improving consumer experience. The extra money made over the mutually-agreed daily amount was shared between the operator and Chalo.

Dubey dangled a bait: Guarantee money. The business proposition for bus operators in Bhopal was simple: The daily revenue of buses—whatever it was—was paid by Chalo every day in the morning. In return, Chalo took care of automation of daily operations, vehicle tracking, in-bus electronic ticketing, bus consumables and cost savings on fuel. The idea was to increase ridership and reliability by scheduling buses on time and improving consumer experience. The extra money made over the mutually-agreed daily amount was shared between the operator and Chalo. Dubey started with one bus, and gradually increased to 100 in Bhopal. Within three years, Chalo got over 6,000 on its platform. The business prospered post the lockdown last March. People wanted a safer mode of transportation. Dubey’s full-tech stack offering—mobile passes. electronic ticketing and smart card for payment—found ample takers among bus owners who stopped taking guarantee money. From 8.7 million rides per month in April 2019, the number jumped to 22 million in March 2021. “Buses,” stresses Dubey, “are Covid proof.” Chalo, he lets on, grew by three times during the pandemic in terms of number of buses added on the platform.

Dubey started with one bus, and gradually increased to 100 in Bhopal. Within three years, Chalo got over 6,000 on its platform. The business prospered post the lockdown last March. People wanted a safer mode of transportation. Dubey’s full-tech stack offering—mobile passes. electronic ticketing and smart card for payment—found ample takers among bus owners who stopped taking guarantee money. From 8.7 million rides per month in April 2019, the number jumped to 22 million in March 2021. “Buses,” stresses Dubey, “are Covid proof.” Chalo, he lets on, grew by three times during the pandemic in terms of number of buses added on the platform.  The challenge for Chalo is equally large. The biggest irritant is monetisation. “Monetisation remains a challenge in Bharat,” says Srikrishna Ramamoorthy, partner at Unitus Ventures. This is a price-sensitive market and demonstrating real value is critical to getting users to pay for the product or service; else one needs to rely on other sources such as advertising. On the positive side, he adds, user acquisition costs are coming down and micro transactions are monetisable. “If one can offset costs through newer monetisation models, this challenge could be solved,” he says. Building trust, he underlines, takes time in the hinterland.

The challenge for Chalo is equally large. The biggest irritant is monetisation. “Monetisation remains a challenge in Bharat,” says Srikrishna Ramamoorthy, partner at Unitus Ventures. This is a price-sensitive market and demonstrating real value is critical to getting users to pay for the product or service; else one needs to rely on other sources such as advertising. On the positive side, he adds, user acquisition costs are coming down and micro transactions are monetisable. “If one can offset costs through newer monetisation models, this challenge could be solved,” he says. Building trust, he underlines, takes time in the hinterland.