Were the Republic Day internet shutdowns in Delhi, Haryana necessary?

Experts believe that the shutdown orders did not comply with the standards laid down in the Anuradha Bhasin judgement

Authorities shut down the internet areas in Central Delhi as thousands of farmers protesting against new agricultural laws stormed the Red Fort on India's Republic Day. Photo by Naveen Sharma/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Internet services were shut down in areas of Delhi on the afternoon of January 26 until midnight “in the interest of maintaining public safety and averting public emergency”. All 3G and 4G services were also suspended and mobile services were throttled to 2G speeds (up to 64 kbps) in the national capital. The orders were uploaded to the website of the Union Home Ministry after noon on January 27.

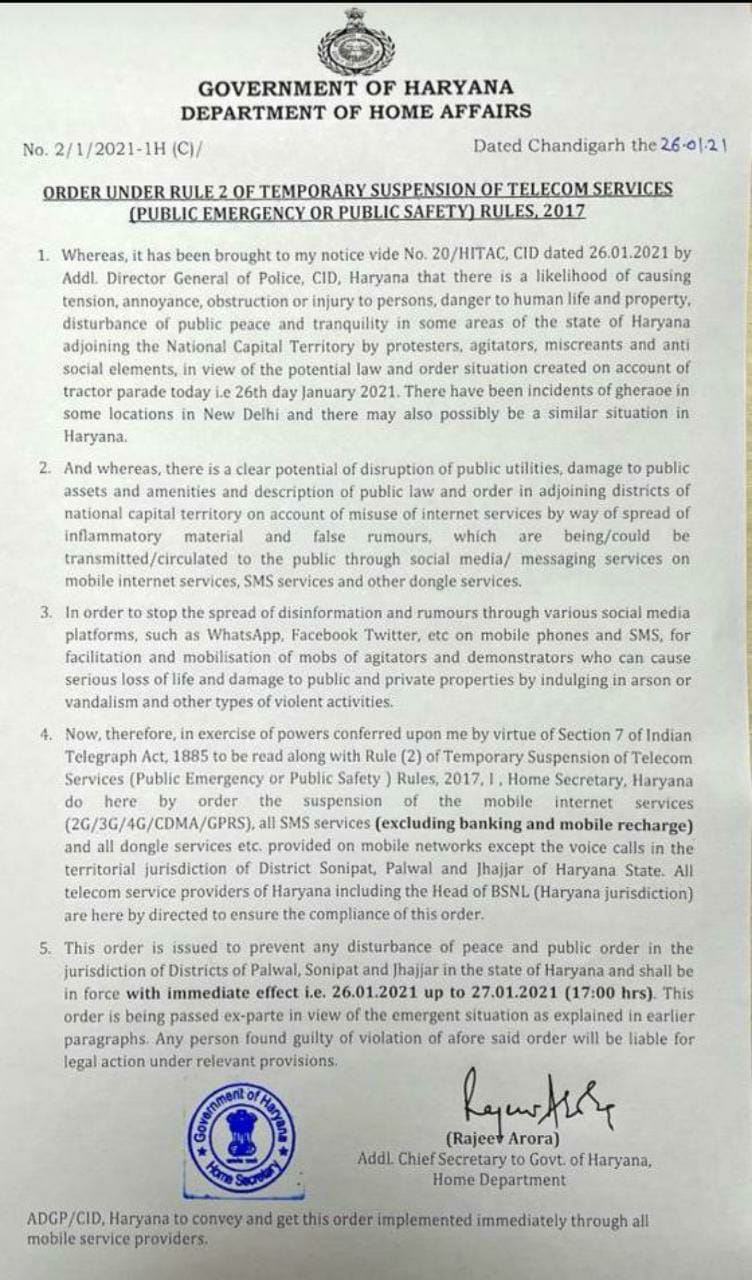

Similarly, all mobile internet and SMS services (except banking and mobile recharge), and dongle services have been suspended in Sonipat, Palwal and Jhajjar districts of Haryana until 5 pm on January 27 to “stop the spread of disinformation and rumours” through social media platforms and SMS.

In Delhi, internet services were suspended in Singhu, Ghazipur, Tikri, Mukarba Chowk, Nangloi, and their adjoining areas. All are neighbourhoods close to the Delhi border and violence broke out in some of the areas during the farmers’ tractor rally on Republic Day. In Mukarba Chowk, for instance, the Delhi Police fired tear gas shells at the farmers, according to a PTI report. Farmers broke through police barricades to enter Delhi via Tikri and Singhu, the Deccan Herald reported.

Multiple people in Delhi told Forbes India that they continued to receive messages from their telecom service providers even early on January 27, informing them about the ongoing internet shutdown.