Who Do Oil Companies Turn to When There's a Spill?

Cleaning up oil spills takes money, equipment and skill. Oil Spill Response, a non-profit co-operative, is the first port of call for those attempting a clean-up

When the MSC Napoli, a container ship, was beached off the coast of Cornwall in England three years ago, not everyone was distressed by the tonnes of bunker oil from the ship’s tanks making its way to the shore. With the oil slick, the tide also brought in containers filled with all manner of goods including BMW motorcycles and automobile spares. Police had to be brought in to patrol the shores, as people made off with the goods, adding to the difficulty of dealing with the ship and the oil on the beaches. The collision between container ship MSC Chitra and MV Khalijia off Mumbai on August 7, 2010 has some similarities with the Cornwall incident. Here too, people foraged around for packets of chocolates and other goods washed ashore.

Oil spills, especially those that take place on water, have more in common than the propensity of locals to make off with stuff that comes their way. Increased offshore drilling and transportation of fuel by tankers across greater distances has led to a gradual increase in the number of incidents over the years. The odds of something going wrong have gone up because companies are venturing into more difficult areas to find the oil. The big difference between spills in the past and now is that a major accident could cost billions of dollars to deal with. British oil company British Petroleum, whose leaking Macondo well put close to a million tonnes of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico in three months, is looking at clean-up costs and claims that could go up to $30 billion — an amount that could well take the company to the cleaners.

One way to deal with such incidents is to asses the risks regularly and prepare to respond quickly in an eventuality, says Sudhir Vasudeva, ONGC’s director for offshore operations.

Oil Spill Response (OSRL), a company now owned by 36 oil majors including ONGC, was formed to do exactly this. Over 25 years of its existence, the not-for-profit organisation, has become the first point of contact for almost all oil-spills. It employs about 150 experts divided between three bases in Southampton, Singapore and Bahrain and carries a $50 million inventory of equipment including aircraft that can spray dispersants, ready for deployment in an emergency. Most of these experts have attended to at least 10 oil spills; some like Daniel Chan have dealt with several more. Chan is deputy operations manager in Singapore, and is leading the first team on the Mumbai spill.

Spill Co-operative

A key aspect of their job is to identify the nature of the spill and figure out how to minimise the impact. But this can often be complicated by circumstances peculiar to the incident. In Mumbai for instance, the response team discovered that some of MSC Chitra’s falling containers contained canisters full of pesticides, which if cracked would release phosphine, a toxic gas. Many of these washed onto beaches at Elephanta Island and Alibag. Responding quickly, the group was able to figure ways to prepare for the increase in toxicity levels around the ship. They set up gas monitors to check air quality and built an advance medical post on the island, putting in capability to deal with people impacted by the gas. Fortunately, the need did not arise as most of the canisters were retrieved.

Spill response teams working at BP’s Macondo well too had to deal with similar problems. The crude oil gushing out at the bottom of the sea contained gas, which released toxic vapours when it reached the surface. Engineers trying to drill an alternate well to reduce the pressure from the gusher at the bottom of the sea could not get close enough to work at the site. They had to respond quickly by spraying dispersants on the surface of the water to lower the gas concentration. They were also provided breathing apparatus to get closer to the leak without being in harm’s way.

“As oil companies go further and deeper in search of oil, they have to train to respond in harsh terrains and bad weather,” says Thomas Liebert, global head of operations for OSRL. They are advising Cairn plc on building spill-response capacity in Greenland, where the Scottish company is now drilling exploratory wells.

Liebert says spill response work is time consuming and can be very tough in remote areas. In an incident very similar to the BP spill, when the Montara oil platform in the Timor Sea off Indonesia blew out in late 2009, it leaked oil for almost three months. It did not attract as much global attention because it occurred virtually in No Man’s Land — a part of the sea shared by East Timor, Indonesia and Australia. The only way to contain the slick, spread over 3,000 square kilometres at sea, was to put booms (floating barriers) around the largest parts and start scooping up the top layer of oil and water. To achieve this was no mean task. Teams of response experts had to spend weeks at sea, trying to find the slicks and then trap them in the booms. “Fortunately for us, the oil was waxy and formed a thick, chocolate mousse-like layer over the water. Since the patch was thick, it stayed together and could be chased and contained into the booms,’’ says Liebert.

One technique used for most spills in the sea, is to go in with two vessels — one small and the other large — and try to put a boom around the slick area. Once the slick is enclosed, a skimmer that empties into the storage tank of the larger ship sucks it in. While battling oil leaks, success often depends on how well timed the response is. Failure is common. Three years ago, when crude carrier MT Heibei Spirit, a crude carrying ship collided with a barge off Daesan port in South Korea, its hull was punctured and it started leaking oil rapidly. About 10,000 tonnes of oil leaked into the sea, in the worst oil spill incident in Korean history. The government took too long to mobilise international help, and tried to deal with the spill the best it could. About a fortnight after the spill, OSRL aircraft were finally mobilised to spray dispersants on the spill, but the move was not effective. They could not find much floating oil, since it had already emulsified. “Most of it had reached the shore and 30 beaches were affected,” say industry experts involved in the incident.

Clean-up Costs

With every spill, costs of dealing with spilt oil are mounting. Insurance company reports say the costs have peaked with the BP spill. For the Exxon-Valdez oil spill at Alaska, the cost of clean-up worked out to $52,000 per tonne. In the more recent past, costs have shot up several folds. For the Pacific Adventurer, a ship that got caught in a storm in Australia and spilt bunker fuel in 2009, the cost was $100,000 a tonne. For the BP well in the Gulf of Mexico, spill related costs are already at $8 billion and the claims are still coming in.

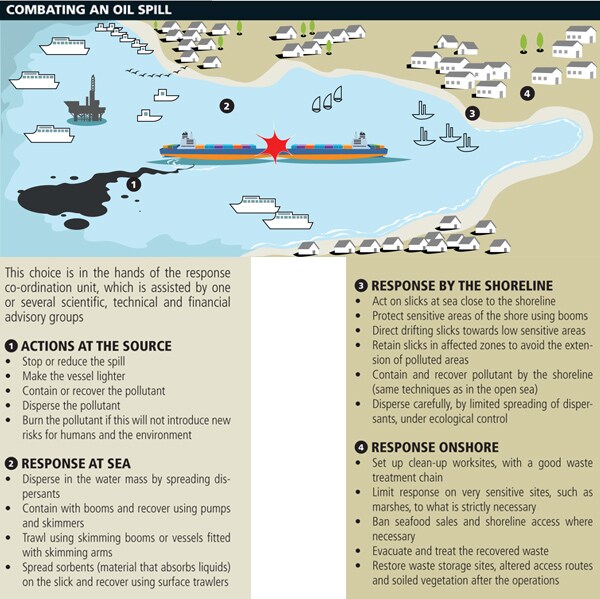

Infographic; Sameer Pawar

Oil spreads fast and in Mumbai too, the approximately 400 tonnes of bunker oil that spilled into the Arabian Sea from MSC Chitra is slathered in a thin layer over sand, rocks and mangroves all around the area. Ironically, oil experts have been trying to convince Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust (JNPT) officials to be prepared for oil spills, by investing in equipment and training. In India, the Coast Guard deals with offshore oil spills and the ports are reluctant to invest in any measures. Eventually, even equipment like low-pressure water sprays, that are used to wash the rocks clean of oil, had to be flown in from London.

“With the increased offshore oil and gas activity in India, there is much more risk and it is critical to be prepared,’’ says Liebert. The unidentified oil that has washed onto Goa in early September, tarring the beaches just before the start of the winter tourist season, is one such incident. Liebert says, there is more awareness on environmental issues, but there is a disconnect between the oil companies and assessment of the risk that they are taking. It is not just the volume of oil that has leaked, sometimes even a small quantity spilled into a sensitive environment can do a lot of harm, he says. In India, the authorities tend to perform risk assessment based on the volume of the spill and not on the environmental risks and location.

Dealing with Waste

One big problem is that of managing waste collected from the spill site. In Elephanta, for instance, volunteers have collected about 50 tonnes of plastic — mostly bags and bottles, after cleaning up the beach. Pushing away the oil from the rocks with high pressure jets also pushes away the rubbish, which obviously cannot be left there. French authorities who went looking for storage space for 250,000 tonnes of waste collected from beaches after the Erika incident (where an oil tanker broke in two off the coast of France) in 1999 found storage was taken up by debris from a previous incident in 1979 that was yet not disposed. The waste has to be usually recycled several times before it can be put back into any kind of use.

One way to reduce this would be to use bio-remediation — that is, bacteria that chomp up the oil molecules. This is being tried for the first time on a large scale in Mumbai, where oil eating bacteria provided by The Energy and Resources Institute (Teri) are being used to battle the spill. The Maharashtra Pollution Control Board and hundreds of volunteers have applied the micro-organisms to neutralise the oil. Fortunately in Mumbai, the impact on wildlife has been minimal. Handling of oiled wildlife, as animals affected by oil spills are called, is another specialised dimension of dealing with spills. Among those leading in this field is the Belgium-based Sea Alarm, an agency that has been active in responding to distressed wildlife in various parts of the world.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)