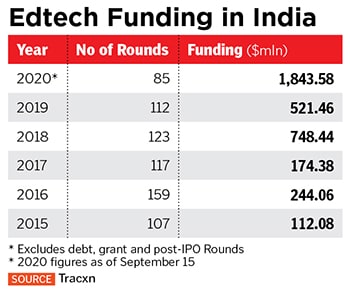

Cover story: Can Ronnie Screwvala do a UTV with upGrad?

Build, scale, repeat: Ronnie Screwvala, who transformed UTV from a production company to a multimedia conglomerate, is now dipping into his entrepreneurial genius to build ed-tech startup upGrad into a venture of scale and impact

Ronnie Screwvala

Ronnie ScrewvalaImage: Mexy Xavier

Barely five minutes into my Zoom meeting with Ronnie Screwvala, I earn my first strike when I call him a serial entrepreneur. “It’s a word I’m going to put a cross on,” says the 64-year-old.

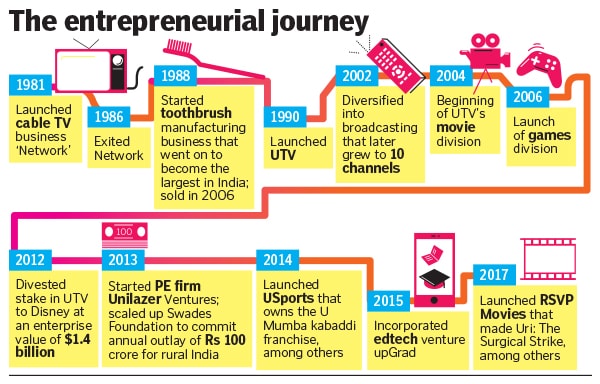

I prime myself for a debate. After all, what better sobriquet to describe a man who has pioneered a slew of businesses since the 1980s—cable TV ‘Network’ in 1981, a toothbrush manufacturing unit, Lazer Brushes, which went on to become the largest in the country, media and entertainment company UTV, which would eventually be sold to global giant Walt Disney. Right now, Screwvala is the founder of a bouquet of companies, which includes edtech venture upGrad, PE firm Unilazer Ventures, film production house RSVP Movies, sports business U Sports, and not-for-profit Swades Foundation. I surely had an easy debate to win, right? Maybe not.

“A serial entrepreneur is one who builds or buys something with a clear intent to sell it in time. I have never started any business with an intent to exit, ever,” says Screwvala. “Serial by definition means pre-meditated and it goes against my core motto for entrepreneurship: Staying the course to create maximum value. It took me 20-plus years to build UTV and I never planned in my second year that I will sell it off 18 years on. Of the 2,000 to 3,000 people who emerged from the media, I probably stuck to it longer than most.”

Instead, what drives Screwvala, a first-generation entrepreneur, every time he builds a venture from ground up is scale and value. Consider that he started UTV as a TV production company in 1990 with all of ₹37,500. By the time he divested his stake in 2012 (about 23 percent at the time), it had an enterprise value of $1.4 billion and had grown into a conglomerate that, at various points along the journey, housed broadcast channels, a movie division, an animation studio and a games vertical, among others.

In 2015, Mayank Kumar joined Ronnie Screwvala to launch upGrad

In 2015, Mayank Kumar joined Ronnie Screwvala to launch upGradImage: Courtesy UpGrad

In its early days, UTV created content for state broadcaster Doordarshan with the standard format of 13 to 26 episodes; when satellite television forayed into India in 1992, Screwvala sniffed scale and offered private broadcaster Zee TV a whopping 520 episodes a year across 10 shows. In 1994, he took his formula to Doordarshan with Shanti, a daily soap that ran for three years with nearly 800 episodes. There was no looking back since.

The itch to build and the hunger for impact stayed on even after Screwvala stepped down from UTV, and it took him just a 10-day vacation to New Zealand, his longest break that decade, to figure that out. To what next, he had a simple answer: More of the same; start all over and build from scratch. In the not-for-profit sector, it meant scaling up Share, a creche and an orphanage on the premises of the UTV office since 1990, into the Swades Foundation (along with wife Zarina) and committing an annual outlay of ₹100 crore for rural initiatives, while, on the entrepreneurial front, he considered three options—consumer goods, healthtech and edtech.

“I felt I could add nothing to consumer goods, while healthtech was interesting but not my forte. Education appealed to me as the core of building a successful and highly-valued business where I could bring my learnings of the last decade and a half,” says Screwvala. “It was also a sector that could have a high impact for the next two decades and was ready to be disrupted, where bold bets would lead to much greater rewards.” His convictions have been confirmed by a June 2020 report jointly

released by consulting firm RedSeer and investment firm Omidyar Network India that pegs the edtech market to grow by $3.5 billion by 2022; of this, the K-12 market is expected to grow 6.3 times to $1.7 billion and post-K-12 by 3.7 times to $1.8 billion.

As he tested the waters, Screwvala connected with Mayank Kumar, then a vice president at Bertelsmann, a European media, services and education company. “During our first meeting at his office in Mumbai we exchanged notes on the sector,” says Kumar. There was radio silence from both ends for a few months before Screwvala pinged Kumar again. “He asked if I would be open to taking the entrepreneurial plunge with him. My first answer was no, as I had just moved to Delhi and had a baby. But, on second thoughts, there’s never a good time so to say, and the idea of starting something was always at the back of my mind.”

Kumar himself was looking to invest in education in India, but didn’t find the right avenues. With Screwvala, the pieces fell into place. “Education requires long-term thinking and the conversation with Ronnie gave me the sense he had that perspective. Plus, Ronnie is someone who has scaled up businesses. I thought it would give me enough bandwidth and focus to build a business with him rather than for an investor whom you have to convince three years later about what you were doing,” says Kumar. In 2015, the two and co-founder Phalgun Kompalli came together to launch upGrad, kicking off Screwvala’s second innings as an entrepreneur.

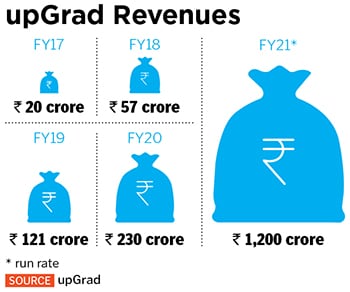

By the time upGrad was incorporated, Screwvala had already set up Unilazer Ventures, and U Sports, the owner of kabaddi franchise U Mumba. But he hands out my second strike when I call upGrad an addition to his business portfolio (which in 2017 also came to include RSVP Movies). “It’s not,” he says. “A portfolio for me is something like a LensKart where I have invested through Unilazer, and U Sports and RSVP are my passion projects. UpGrad is to me now what UTV was in my first innings. I am looking at it as an entrepreneur, a founder, with a full hands-on role as executive chairman. If I do not achieve at least 10-15x in scale, impact and value creation in half the number of years than what I did in media and entertainment, it will be a personal disappointment.”

His years in the media and the entertainment industry have given Screwvala a feel of the pulse that helps in putting across brand messages in a lucid and cogent manner. First-time director Aditya Dhar and Sonia Kanwar, creative producer at RSVP, had approached Screwvala rather diffidently with the script of Uri: The Surgical Strike and their choice of Vicky Kaushal as the lead. But Screwvala, quick to identify that the storyline will resonate with viewers, vetted the movie in five minutes. Uri, made with a budget of about ₹25 crore, returned with over ₹244 crore in India and a rich haul of National Awards. In edtech too, Screwvala brought this understanding of the audience, with a keen eye on scale, helping upGrad tone down its initial “hoity-toity” communication line to reach a larger consumer base.

His years in the media and the entertainment industry have given Screwvala a feel of the pulse that helps in putting across brand messages in a lucid and cogent manner. First-time director Aditya Dhar and Sonia Kanwar, creative producer at RSVP, had approached Screwvala rather diffidently with the script of Uri: The Surgical Strike and their choice of Vicky Kaushal as the lead. But Screwvala, quick to identify that the storyline will resonate with viewers, vetted the movie in five minutes. Uri, made with a budget of about ₹25 crore, returned with over ₹244 crore in India and a rich haul of National Awards. In edtech too, Screwvala brought this understanding of the audience, with a keen eye on scale, helping upGrad tone down its initial “hoity-toity” communication line to reach a larger consumer base.

Kumar leans on Screwvala for strategic and scaling guidance as well. Every time he’s put a number to a target, Kumar says, “Ronnie just ups, ups and ups it.” And with his strong bias for action, Screwvala ensures the targets are met. “During the early days, we would discuss an idea for 10 to 15 days and then Ronnie would just get us to push it out. Agar kuch hai toh karo [if there’s anything to be done, let’s do it] is his motto.”

“The impetus to start something would always be Ronnie’s. His head would bubble with ideas. He would take a piece of paper to bed and wake up in the middle of the night scribbling them down,” says Deven Khote, a co-founder at UTV and five years Screwvala’s junior at Cathedral & John Connon School in Mumbai. “What made UTV work was an entrepreneurial model where a new business would be set up, people would be brought in to run it and the minute it gained traction, Ronnie would be on to his next business idea.”

*****

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

.jpg?impolicy=website&width=122&height=70)

A still from Uri: The Surgical Strike that earned ₹244 crore in India

A still from Uri: The Surgical Strike that earned ₹244 crore in India

Kabaddi team U Mumba at a game during season 7 of the Professional Kabaddi League

Kabaddi team U Mumba at a game during season 7 of the Professional Kabaddi League