There's much to learn from the hacks of small organisations: Paulo Savaget

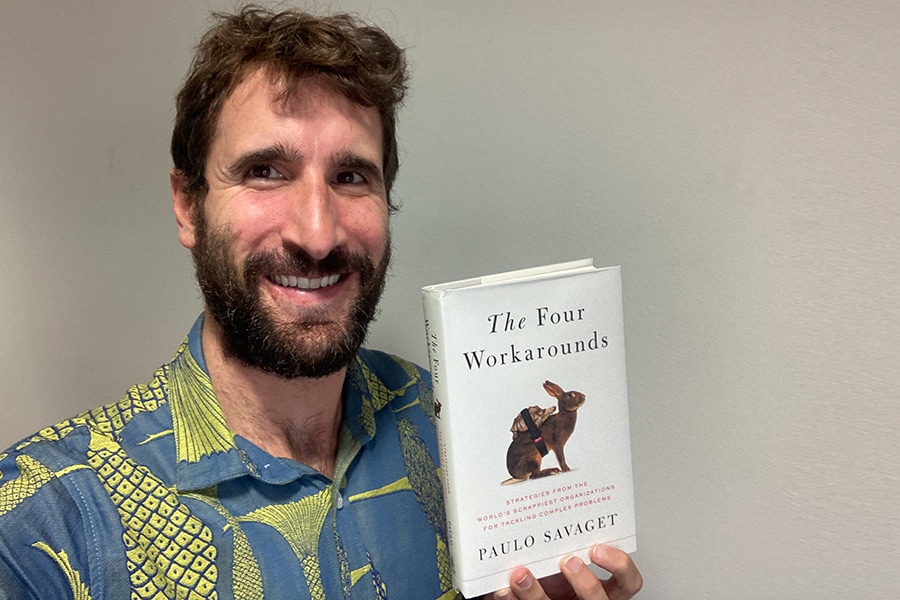

Paulo Savaget, author of The Four Workarounds, and an associate professor at Oxford University's Engineering Sciences Department and the Saïd Business School, talks about four unconventional ways to work around problems

Paulo Savaget, an associate professor at Oxford University's Engineering Sciences Department and the Saïd Business School

Paulo Savaget, an associate professor at Oxford University's Engineering Sciences Department and the Saïd Business School

Large companies are considered to be inherently superior, better run, and better equipped than scrappy organisations and intrepid entrepreneurs. But Saïd Business School’s Paulo Savaget has a contrarian perspective. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Q. Could you give us a peek into the book’s backstory?

I didn’t plan to study workarounds; I bumped into them as I searched for resourceful ways to tackle complex problems. More specifically, I noticed the value of workarounds when studying computer hackers. The essence of the hacker approach is that they weave through uncharted territory and, instead of confronting the bottlenecks that lie in their way, they work around them. I also learned that hacking isn’t limited to the world of computing–many scrappy organisations worldwide hacked their problems. From working around their obstacles, they addressed critical issues and were sometimes able to leave a powerful legacy, especially when it came to issues that, despite best efforts, seemed intractable.

Q. What value does a ‘workaround’ offer in contrast to the conventional approach?