Ajay Shah: The State Should Enter the Picture Only When Markets Fail

A key pillar of a sound state is accountability. Alongside precise objectives and precise powers, we need layer upon layer of accountability mechanisms

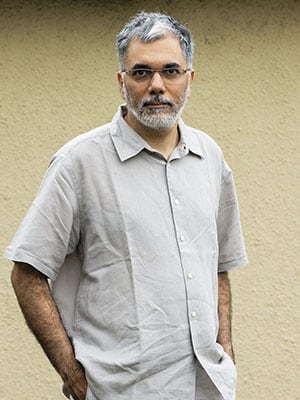

Ajay Shah

Profile: Ajay Shah co-leads the Macro/Finance Group at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy in New Delhi. Before this, he was a consultant in the Mini-stry of Finance’s Department of Economics. He has engaged in academic and policy-oriented research in economics and finance.

The corruption scandals of recent years have thrown a spanner in traditional ways of doing business in India. That murky ways of doing business are much less feasible is something to rejoice over. But equally important is the challenge of constructing new structures that are impartial, efficient and supportive of growth. The way forward lies in clarity of objectives, focusing the government on market failures and refraining from arbitrary meddling, and ensuring accountability.

In the bad old days, India had a mix of badly structured government rules and procedures, coupled with large scale corruption. In areas which required a strong interface with the government, many success stories in the world of business had murky ways of getting things done. When foreign investment and private equity surged into the country 2002 onwards, this capital was often quite amoral. They cared about getting returns and not about the means through which returns were obtained.

With this wind in their sails the strongmen of Indian business thundered ahead. Their ranks were augmented by many wannabes who saw the opportunities available by flouting rules, getting things done, crushing rivals through illegal methods, and getting to the prize of billion-dollar valuations offered by private equity or FIIs.

From 2002 to 2008, we got the greatest macroeconomic boom in India’s history, but alongside it, we also got some of the most dangerous behaviour by strongmen and their counterparts in the government. By 2007, many people started getting concerned about whether India would fall into the ‘middle income trap’, which has been observed in many other developing countries where government and business cosy up in corrupt arrangements, kill off honest businesses, and settle into cosy stagnation.

This picture has changed quite a bit in recent years. While enforcement mechanisms in India are not perfect, it is also the case that not all enforcement can be bought off. One by one, we are seeing a procession of companies crashing and burning as skeletons come out of the closet.

Of great importance is stock market performance. The companies that have got into trouble in this fashion have produced phenomenal underperformance of the broad market. Sometimes, we see 50-70 percent fall in returns in a short time after an enforcement action. At other times, we see sustained long-term failure to deliver returns.

These messages have got to Wall Street. The same private equity and FIIs who blindly supported strongmen are now very concerned about ethical standards. A new line of business has opened up, in serving these investors, of doing ethics checks in India. But what about the apparatus of government?

The strongmen in business were exploiting opportunities that were present in a malfunctioning government. On one hand, this is about messy processes with a lack of clarity, a lack of rule of law and arbitrary decision-making. In addition, even when these processes are operated by a clean organisation, there are serious concerns about the inadequacies of our state apparatus.

The RBI, despite being a ‘clean’ organisation, has failed to deliver

As an example, consider the Reserve Bank , arguably a singular success story in India on the question of corruption. Every other government agency envies the RBI when it comes to cleanliness all the way down to the rank and file.

This cleanliness has not led to success on core functions. For most of the last 40 years, RBI has failed in achieving price stability, which is the dharma of a central bank. In the financial regulatory aspects that RBI engages in, there is a long history of failure: RBI has failed to create a banking system, a payments system and a bond-currency-derivatives nexus of the sort that is required for India’s growth. RBI is complicit with bad policies emanating from the Ministry of Finance when it comes to nurturing public sector banks, and when it enables reckless fiscal policy in its function of being investment banker to the government.

Even in the hands of good men, why did RBI fail?

The first issue concerns unrestricted meddling by the state. The present laws and agencies were constructed in the age of socialism, when it was thought appropriate to give draconian powers to government agencies.

This strategy is a recipe for trouble, for public bodies will almost surely misuse these powers. It makes much more sense to focus the government upon the narrow task of addressing market failures. Market failures come in three kinds: Those associated with market power (such as abuse of monopoly), asymmetric information (eg when you eat at a restaurant, you don’t know whether the kitchen is clean) and externalities (eg, a factory emits pollutants that harm you). These three groups of market failures justify government intervention—there is no case for any other government intervention.

We must reconstruct public bodies around clarity of objectives (to address market failures) and equip them with the minimal set of powers required to pursue market failures. This requires great care in writing laws that clarify objectives in detail, in avoiding vague phrases such as “shall pursue the public interest” and in writing down precise and limited powers to pursue these objectives.

The third pillar of a sound state is accountability. The first and foremost accountability mechanism, of course, is clarity of objective. An agency can be held accountable when everyone knows what it is supposed to do. We know what the Election Commission is supposed to do. We do not know what the RBI is supposed to do. The contrast in outcomes is striking: By and large, the Election Commission has delivered on holding free and fair elections.

These ideas were employed by the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission, chaired by Justice BN Srikrishna, in drafting the Indian Financial Code that aspires to replace all existing financial law. When enacted by Parliament, this will give a quantum leap in governance in the field of finance. This strategy of public administration reform would be valuable in India in fields far beyond finance.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)