What did the AI say?

Healthtech startups in India are using artificial intelligence and machine learning capabilities to bring health care services to underserved and unserved areas

Adarsh Natarajan, CEO, Aindra Systems, with the Edge device which uses AI to screen samples for cervical cancer

Adarsh Natarajan, CEO, Aindra Systems, with the Edge device which uses AI to screen samples for cervical cancer

Image: Hemant Mishra for Forbes India

The World Health Organization (WHO) says that every country should have at least one doctor per 1,000 people. But like 45 percent of its member states, India lags way behind. It has less than one doctor per 1,000 people, 0.758 to be precise, according to WHO.

As of 2010, 30.9 percent Indians lived in urban areas, and 29.4 percent or 104.7 million of the urban population lived in slums, latest United Nations data shows. A health care system with basic and quality health care services restricted to urban and semi-urban areas, especially private hospitals, has kept accessibility and affordability low for most of India’s population. The situation is deplorable when it comes to government hospitals. One doctor has to look at 11,082 patients, Minister of State for Health and Family Welfare Anupriya Patel told the Lok Sabha on July 20 this year.

Is the answer more doctors? A study by the Indian Journal of Public Health says India would need 2.07 million doctors by 2030, a near impossible target. “Accessibility to health care services really drops as you move to smaller cities and remote areas,” says Manish Singhal, founder, pi Ventures, an early stage fund investing in artificial intelligence (AI)-led startups. “Training more doctors is not feasible; it takes time and quality output is not guaranteed.”

The only way to improve accessibility in a low-cost manner is through technologies that can extend human knowledge and experience, he says. “AI is best suited because of its human-like intelligence that can take a lot of decisions better than humans can.”

Rapid advancements in AI, large data sets from open source universities, big hospitals and research organisations, and access to capital have allowed Indian startups to enter the healthtech space. These founders are striving to change the health care scenario in India using machine learning (ML) and creating their own low-cost portable hardware. These startups use available data to train their algorithms to identify and analyse diseases at the point of care. If adopted at scale, with a large part of the initial diagnosis left to machines, India’s limited medical professional resources can be used efficiently.

COO Prasad Bhat (left) and co-founder and CEO Rahul Shingrani of Ten3T with Cicer, the palm-sized wearable device which can read a patient's vitals

COO Prasad Bhat (left) and co-founder and CEO Rahul Shingrani of Ten3T with Cicer, the palm-sized wearable device which can read a patient's vitalsImage: Hemant Mishra for Forbes India

“Three fourths of medical emergencies actually happen outside the intensive care unit (ICU). This is true everywhere,” says Rahul Shingrani, CEO and CTO of Ten3T. With this intelligence, Shingrani and his co-founder, Sudhir Borgonha, created a wearable device that allows doctors to monitor patients in real time and avoid emergencies.

Named after the 1,03,000 times a human heart beats in a day, Ten3T manufactures Cicer, a palm-sized reusable sticker that can be stuck to a patient’s chest for a few hours to a couple of weeks for remote monitoring. It can read ECG, heart rates, respiration rates, blood oxygen levels, patient postures and temperature, and create a report in 30 seconds to send it to a doctor’s smartphone or central monitors.

Ten3T’s AI and algorithm reads the heartbeat data segmented by Cicer “to predict any abnormality and whether a patient is going to deteriorate soon,” Shingrani says.

Apart from heart patients, it can be used for post-operative care, pre-natal care, and panic attacks. Ten3T is in talks with the Indian Army for use in high altitude remote areas.

Ten3T started operations in 2014 and launched commercially only a year ago. It caters to hospitals, renting out its devices and supporting infrastructure like large-screen monitors. Plans are afoot to launch a smaller device for consumers in the next 12 months, who can buy the patch and download the app to monitor their vitals.

Personal Therapist

Nearly 56 million Indians suffer from depression, and 38 million have anxiety disorders, says a 2017 WHO report. That is about 7.5 percent of the population. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare says India needs 11,500 psychiatrists, but has only 3,500.

Wysa Buddy, a penguin chatbot, was launched in January 2017 as a mood recorder that asked users how they were doing, every day. Trials on a focus group showed reduced depression scores, leading the co-founders to conclude that “people didn’t want to talk to another person fearing judgement but still wanted to feel heard,” says Vempati.

Wysa’s app has three tiers. In the first level, the chatbot asks basic questions and recognises emotion. It can play back good memories on a bad day. The second level has therapeutic tools encoded in conversations. It offers guided meditation, mindfulness techniques, breathing techniques, cognitive behavioural therapy techniques, according to the mood it perceives. The chatbot has about 50 AI models to recognise different emotions. The 30 million conversations it has had with people around the world—it has users from over 30 countries—help in training.

“We mostly use AI to listen. It allows personalisation and scalability, while users feel heard empathetically and without judgment. A chubby little AI penguin fits in well,” Vempati says. The third, and the only paid tier, provides a clinical psychologist ‘coach’. At about ₹1,900 a month, Wysa claims to provide access to a mental health professional at one-fourth the usual cost.

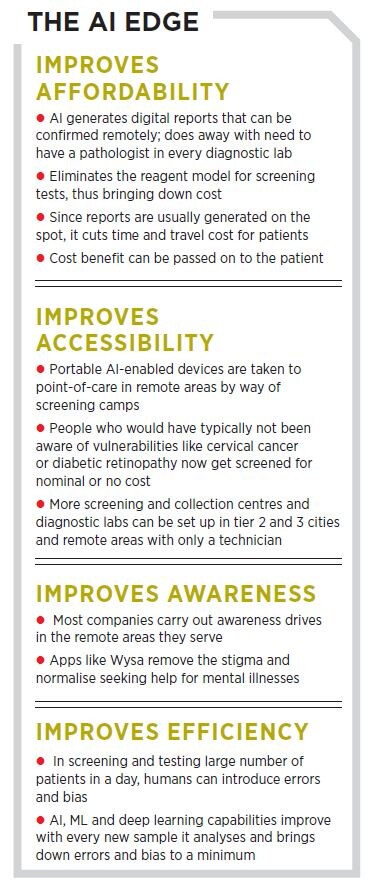

Cancer Screening

“Cervical cancer is the largest killer of Indian women; technologies like AI, optics and mechatronics can change that statistic,” says Adarsh Natarajan, founder, Aindra, an AI-powered healthtech company.

Aindra was initially setup as a software company, with resources focussed on developing AI models to screen cervical cancer. It shifted gears when Natarajan realised “no real change will happen if we can’t take our solution to the point of care.”

So Aindra “backward integrated and developed hardware components that could be taken to point of care,” he says. Apart from a tie-up with Fortis Hospital, which deals with the lifecycle management of cancers [from diagnosis to treatment], Aindra has partnerships with diagnostic labs and gynecologist clinics. Working with NGOs like Cancer Care India and Mahati Trust takes it to the rural areas.

“It’s all a chain reaction; improve accessibility, and affordability will get better,” he says. Traditional tests can cost between ₹800 and ₹2,000, plus the cost of travel and time. Aindra’s screening costs ₹300 to ₹500. “Nearly half of patients opt out of treatment if the result is not given on the same day,” says Natarajan. Traditionally, it takes four to six weeks to get results for a cervical cancer test, whereas Aindra can do it in a couple of hours, he claims.

A technician at a clinic or camp with Aindra can collect the test samples; it is then stained by chemical reagents (which make the cells visible under a microscope) and a digitised image of the slide is fed to the AI. “The AI allows us to look for clinically significant parameters, take clinical data to make a decision on the sample, and even the extent of the cancer,” says Natarajan.

A pathologist sitting anywhere in the world can confirm the result. “Reinforced learning and AI retraining through pathologists’ confirmations make it a continuously learning system. AI and ML are central to what we do. Without it, we would not have a meaningful way of achieving what we want to.”

Aindra has been developing its technologies and hardware since 2015; it is now in the clinical validation phase and has screened 1,000 patients so far. It is also getting a European Union standard CE certification as a self-regulatory measure. “Timely intervention and early diagnosis can dramatically improve the incidence to mortality ratio in cervical cancer,” Natarajan says.

Rajarajeshwari Kodhandapani, co-founder and director of Artelus, which is taking diabetic retinopathy screening to the forgotten billion

Rajarajeshwari Kodhandapani, co-founder and director of Artelus, which is taking diabetic retinopathy screening to the forgotten billionImage: Hemant Mishra for Forbes India

Tests for the Masses

Artelus, a deep learning technology platform, was set up by four co-founders—Pradeep Walia, director; Rajarajeshwari Kodhandapani, director; and Lalit Pant and Vish Durga—to bring primary health care screening “to the forgotten billion,” Walia says. It uses AI and ML to screen bus and cab drivers and others at the bottom of the pyramid for diabetic retinopathy (DR). It is also developing capabilities for breast and lung cancer, while its tuberculosis and pneumonia screening is in the validation phase.

Diabetic retinopathy, which can cause blindness, can be prevented by early detection. “It is asymptomatic, so by the time the problems arise, it is usually too late,” Walia says. It affects one in three diabetics. “With only 20,000 ophthalmologists and 5,000 retina specialists and 90 million diabetics in India, the doctor-patient gap may take decades to fill.”

That’s where AI comes in. Equipped with affordable ophthalmic cameras and algorithms that can fit on a pen drive, Artelus carries out screening camps every day in Karnataka, in partnership with Dr Agarwal’s Eye Hospital, which is based in Chennai. They screen about 100 people in three hours, whereas traditional tests take at least a day. Artelus takes three minutes from patient registration to generating a report. The screening and analysis process by the AI system takes only 30 seconds. They have screened 25,000 diabetics so far in India.

Artelus’s AI uses a 211-layered deep neural net to identify and classify diseases. It was trained for a year and a half on retinopathy data. “Our core AI platform Tefla can be used to develop applications in the fields of natural language processing (NLP), robotics, drug discovery, and so on. Our custom hardware rack is built using NVidia graphics processing units [GPUs] to accelerate deep learning training,” Walia says.

Artelus is currently working on embedding its AI solution on a chip to eliminate dependency on internet connectivity. The company is hoping this will help take health care to remote areas.

There are two revenue models: Pay per screening for camps and clinics where the cost is usually less than $1, and a bulk licensing model for government and large institutions.

Pathology

A host of reasons brought three ex-American Express employees to health care when they decided to turn entrepreneurs in 2015. There was a social impact opportunity; NVidia had just said GPUs were going to keep getting cheaper, and Google announced plans of investing one-third capital into health care.

“We had a clear intent in mind; solving inaccessibility, inaccuracy and unaffordability which plagues all layers of health care,” says Rohit Kumar Pandey, co-founder and CEO, Sigtuple. After analysing a lot of data and tests, Pandey, along with co-founders Tathagato Rai Dastidar (CTO) and Apurv Anand (COO) decided to focus on common screening tests like complete blood count (CBC).

What started as a contraption of Apple iPhone 6s and a manual microscope, held together by cellphone holders bought from ecommerce portal Alibaba in 2015, is today a full-fledged AI device. AI 100 digitises blood slides and sends the data to its cloud-based platform Manthana. “We use AI for an in-depth analysis of medical images and videos to come up with a comprehensive analysis [of the blood sample] backed by visual evidence,” Anand says. Manthana has been trained by data sets from big hospital chains and laboratories.

A traditional blood test needs a technician, device, reagent, microscope, and pathologist. All these elements are usually not located in the same place—19,000 pathologists serve 3 lakh labs and collection centres in India, Pandey says. Logistics and device add to the time and cost of a blood test.

Sigtuple eliminates the reagent model and “our AI has enabled us to achieve higher accuracy as compared to the de-facto standard of manual analysis. It has also given us an edge over the existing devices or solutions available in the market,” Anand adds. Reports created by Manthana can be approved by a pathologist sitting 200 km away. The entire cycle is completed within 10 minutes. Platforms like Manthana can pave the way for low-cost collection centres in smaller cities with only one technician.

After a go-ahead from the Directorate General of Commercial Intelligence and Statistics, it was launched this April. With 10 deployments in Bengaluru, Sigtuple uses a prepaid or postpaid subscription-based model and also provides in-house pathologists to laboratories, a model that costs slightly more. It charges per report and not for the device. The company is partnering with the government to take the solution to rural areas. It has completed phase two of clinical trials for urine and semen tests, and plans are afoot to bring them to market by year end.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)