How would you price one of the world's great watches?

For companies with lots of innovation stuffed in their products, getting the price right is a crucial decision. Stefan Thomke discusses how watchmaker A. Lange & Söhne puts a price on its 173-year-old craftsmanship

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

When Stefan Thomke finished writing the Harvard Business School case study on A. Lange & Söhne, he sent it to the German watchmaker for feedback. The company’s response was a first for the 25-year Harvard Business School professor: The executives had a question about photos used in a case exhibit.

"We looked at the diameters, and then we actually measured the size of four pictures, and we noticed that the relative sizes of the pictures don’t match the relative size of the watches,” Thomke remembers them saying. “I mean, the diameters range from 38.5 millimeters and 41.9 millimeters, so I don’t know how they noticed this. However, this says a lot about who they are. They go into tiny details and make sure that everything is perfect.”

Perfection and precision are at the heart of A. Lange & Söhne, which produces luxury wristwatches containing hundreds of parts. They make some of the building tools themselves because commercial ones aren’t precise enough. Every watch is hand assembled, twice, in the German workshop. When the first assembly is complete (and working fine), the watch is taken apart, every part cleaned and finished again. A second assembly allows watchmakers to put the most pristine parts, screws, and oil in the perfect locations.

Prices for A. Lange & Söhne products start around $16,000 and climb all the way to $2.6 million for its limited edition platinum Grand Complication, which takes one year to craft.

Capturing value from innovation

The company seemed a perfect model for a study in how to price products. Mainly, how do you think about setting a price for something that is incredibly difficult to produce, full of innovation, and where only a relative few might be manufactured?

“When you think about capturing value from innovations, pricing is quite possibly the most important decision that you’ll ever make,” says Thomke, the William Barclay Harding Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. “My sense from teaching many years is that this was a very interesting issue for executives because companies often don’t get it right.”

A watch connoisseur himself, Thomke had been aware of the company for many years. Not flashy and not mass produced, the watches rank among premier brands such as Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Vacheron Constantin.

Thomke and coauthor Daniela Beyersdorfer, associate director of the Harvard Business School Europe Research Center, had unfettered access to the usually secretive Lange & Söhne's operations, its executives, and the watchmaking shop. Thomke and Beyersdorfer even took turns as watchmakers. “It’s really, really difficult,” he says.

Is the price right?

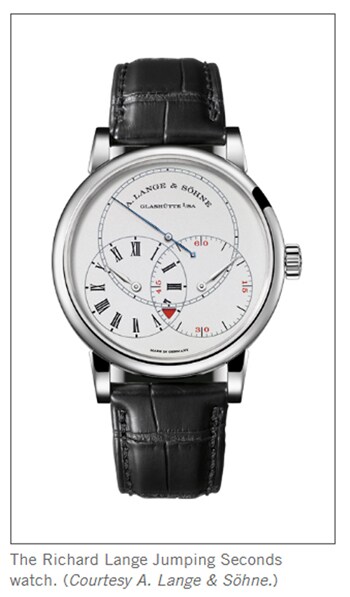

While conducting his research, Thomke saw company executives debating how to set the price for its latest innovation, the Richard Lange Jumping Seconds watch. The CEO, head of production, and head of product development all had an equal say in pricing the limited edition platinum watch.

The dilemma they faced is not uncommon in other industries: Underprice an innovation, and you leave profit on the table. Overprice an innovation, and you may not be able to sell it.

Price discipline is another critical issue. “It’s very difficult to start with a high price and then go down because your customers will get very upset,” Thomke says. “Imagine you're buying a car, and then you find out six months later that the car will cost 25 percent less. It’s terrible.”

The perceived value of an object by buyers is essential, especially if you look at customers as relationships rather than transactions. In those situations, companies may want to "gift" some of the value and not charge as much. For innovative products, the thinking gets even more complicated.

“Usually when you price, you have reference prices because you have comparable products on the market,” Thomke says. “But when you’re creating something that’s really new, often there are very few references. There are no anchors here. So the perceived value or perception then becomes an important factor, and by pricing you can shape perceptions.”

Often companies take the lazy way out, Thomke says. They look at their costs and the margin they need to make, and bingo, there’s the price.

Even though there was no direct reference, innovations like Jumping Seconds have to follow a general roadmap. The product needs to fit into a company's price hierarchy and also the rough price hierarchy of competitors and the market in general. And in the watch's case, the fact that it was a limited edition of only 100 pieces added another wrinkle.

“Some strategic considerations need to go into this," Thomke says. He prefers not to reveal the final price settled on by the company, in order to promote a more lively discussion during class. Let’s just say it’s expensive.

While Thomke’s case study is ostensibly about how to price innovative products, the pricing serves as a trigger point for his classes to start broader discussions about how to grow a sustainable, profitable business. They need to weigh what Thomke calls the P’s: production, pricing, products, and productivity. It also raises the question of whether they want a company that is product-centric or customer-centric, and how they maintain a link to their past.

“There is this balance between [being] innovative, but also you want to be connected to tradition and history. When you look at iconic products, they all have that,” Thomke says, pointing to the Porsche 911, which has changed the technology under the hood but maintained its basic shape. “It’s about evolution rather than revolution.”

The company that started twice

That’s especially true for a company with a rich history like A. Lange & Söhne., founded in 1845 in the village of Glashütte, Germany. It began making precision pocket watches that eventually became world famous. After World War II, the East German country expropriated the company and others like it. Walter Lange, third-generation watchmaker, escaped to West Germany. Some 40 years later, following the country’s reunification, the then 66-year-old Lange returned to Glashütte and began again from scratch.

“Lange started this at an age when most people in the world retire,” Thomke says. "Then kind of like the phoenix rising from the ashes, they started again, and within just a few years they had built this amazing watch company. It's one of the very few companies in this world that was started—and reached the top of its industry—twice.”

While the company is unique in many ways, it holds some general lessons for owners and managers, says Thomke, who used the case in executive education and plans to teach it again this fall. A top company executive plans to attend.

“The case can teach us a lot about how to create an organization that is all about perfection and excellence, an organization that values tradition and history,” Thomke says. “And it also tells us something about entrepreneurship, regarding how you can take something that essentially was destroyed and within a few years make products that are among the best in the world,” Thomke says.

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.