The Amazonification of space begins in earnest

What was once largely the domain of big government is now increasingly the realm of Big Tech, and the people who sold you the internet will now sell you the moon and the stars

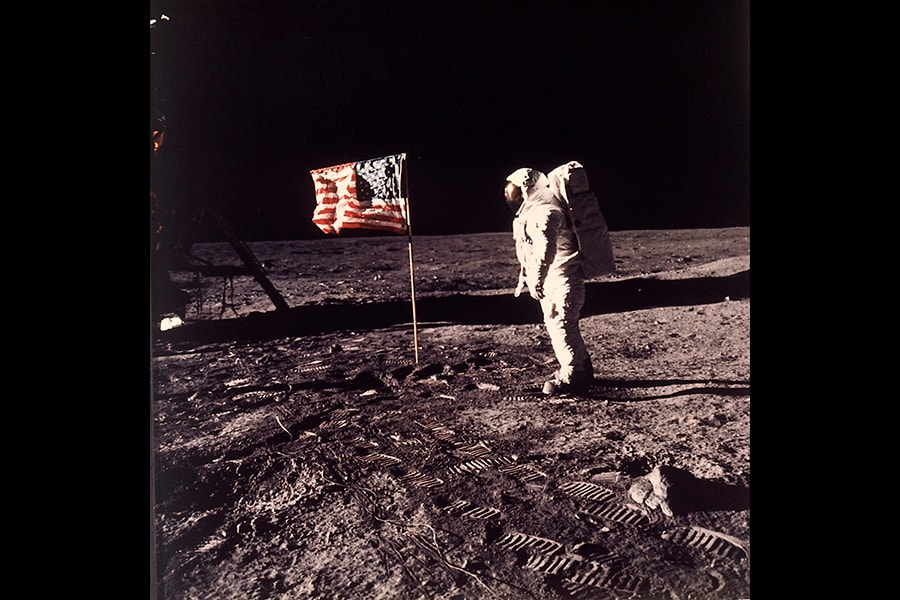

In a photo provided by Neil A. Armstrong/NASA, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin stands on the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. With the suborbital flights made by Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson this month, the privatization of the space industry has crossed the point of no return. Image: Neil A. Armstrong/NASA via The New York Times

In a photo provided by Neil A. Armstrong/NASA, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin stands on the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969. With the suborbital flights made by Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson this month, the privatization of the space industry has crossed the point of no return. Image: Neil A. Armstrong/NASA via The New York Times

The anniversary of the Apollo moon landing marked one small step for space travel but a giant leap for space billionaires.

Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson vividly demonstrated this month that soaring up to the near reaches of the sky appeared safe and, above all, a lark. The planet has so many problems that it is a relief to escape them even for 10 minutes, which was about the length of the suborbital rides offered by the entrepreneurs through their respective companies, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic.

But beyond the dazzlement was a deeper message: The Amazonification of space has begun in earnest. What was once largely the domain of big government is now increasingly the realm of Big Tech. The people who sold you the internet will now sell you the moon and the stars.

Bezos, the founder of Amazon and still its largest shareholder, made clear at the news conference after Tuesday’s flight that Blue Origin was open for business. Even though tickets were not generally available, sales for flights were already approaching $100 million. Bezos didn’t say what the price for each was but added, “The demand is very very high.”

That demand was there even before the world’s media flocked to Van Horn, Texas, for extensive and adulatory coverage of Bezos doing something Branson had done in New Mexico the week before. They saw a carefully orchestrated event, with the world’s oldest-ever astronaut and the world’s youngest along for the ride, capped by a $200 million philanthropic giveaway.

©2019 New York Times News Service