The concept of a leader who knows it all is redundant: Paddy Upton

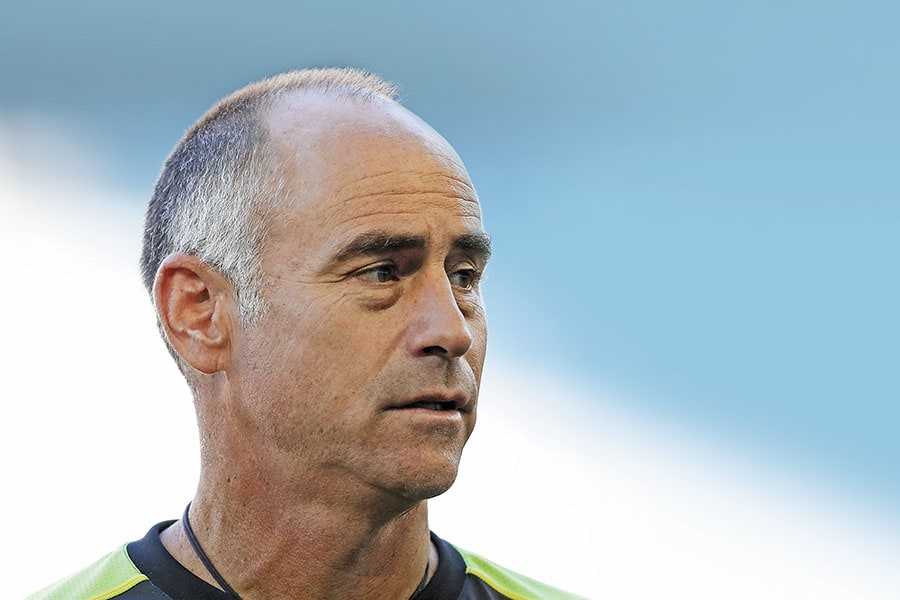

Paddy Upton, head coach of Rajasthan Royals and part of the coaching staff of the 2011 World Cup-winning Indian team, discusses the evolution of modern leadership

Image: Scott Barbour-CA/Cricket Australia/Getty Images

Image: Scott Barbour-CA/Cricket Australia/Getty Images

Paddy Upton’s CV already boasts of associations with top-flight cricket teams: As the physiotherapist of the South African team led by Bob Woolmer and Hansie Cronje, the mental conditioning coach of the Indian team that attained the No. 1 ranking in Tests in 2009 and then went on to win the World Cup in 2011, and the Proteas who were No 1 across three formats between 2012 and 2015. But Upton, a professor of practice at Australia’s Deakin University Business School, would rather be known as a leadership wonk who’s looking to upend the conventional notions of a chain of command, with instructions flowing from the top. In his book The Barefoot Coach, released recently, he gives a peek into his unique philosophy to draw out the best in a high-pressure environment. Upton spoke to Forbes India about the behavioural lessons he’s gleaned from his interactions with top players and how leadership has gone from instruction-based to a collaborative approach.

Edited excerpts from an interview:

Q You were the physiotherapist of the South African cricket team in the mid-1990s, and the mental conditioning coach of the 2011 World Cup-winning Indian cricket team. How did you integrate two professions with seemingly disparate skillsets?

When I was the fitness trainer of the South African (SA) cricket team between 1994 and 1998, the team under coach Bob Woolmer was a leader in terms of sports science. But I felt there was something missing and we could do better. But I could never understand what was amiss.

In my journey over the next four to five years (one among them with a professional rugby team), I came across what was then a first masters degree in leadership coaching. Enrolling for that, I was exposed to what top corporate leaders were doing to bring out the best in their teams, and what academics were saying about how leadership was undergoing a change in the early-2000s.

In the last 200 years, leaders were picked for their domain knowledge and strategic expertise, and they instructed other people on what to do; people were also happy receiving instructions. But the advent of the internet changed where that knowledge and expertise sat—from an individual’s head to out on the World Wide Web. A content expert delivering instructions was no longer a relevant model of leadership. I figured what I always sensed was missing—harnessing the collective intelligence of individual players and helping them become their own best coach.

My research on SA cricket, where I interviewed 21 most-capped players who played under 36 provincial and five national coaches, confirmed what academia and business were saying: What players wanted from their coaches in this knowledge era was different from what they were given in the industrial era command-and-control structure. So it was easy to plot where sports coaching needed to go. But administrative doors were closing on me because it threatened the old-school leaders. The first player I approached was Jacques Kallis: He had gone 14 months without scoring a 100, his father had died, his girlfriend had broken up with him. Through the skills that I learnt through my studying, I did a few personal sessions with Jacques and immediately afterwards, he went on to score centuries in five consecutive Test matches. That’s how I became a mental conditioning coach by default.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Paddy Upton, who returned as head coach of Rajasthan Royals this year, with Steve Smith

Paddy Upton, who returned as head coach of Rajasthan Royals this year, with Steve Smith MS Dhoni (on the ground) with Harbhajan Singh, Paddy Upton, Rahul Dravid and Virender Sehwag. Upton was the mental conditioning and strategic leadership coach of the Indian cricket team from 2008 to 2011

MS Dhoni (on the ground) with Harbhajan Singh, Paddy Upton, Rahul Dravid and Virender Sehwag. Upton was the mental conditioning and strategic leadership coach of the Indian cricket team from 2008 to 2011