Schneider Electric Lays Focus On Data Centres

Schneider Electric’s Jean-Pascal Tricoire is jolting the hidebound French company with a focus on data centers—and American-style capitalism

Five months after he took over as the youngest chief executive in Schneider Electric’s 174-year history, Jean-Pascal Tricoire announced a $6.1 billion bid for American Power Conversion (APC), a Rhode Island company that supplies electrical gear to computer data centres. Investors in what had been considered the General Electric of France responded by driving down Schneider’s stock by nearly 8 percent over two days of heavy trading.

“I was the new guy, and I was buying this new business I didn’t know anything about,” says Tricoire, now 49, of the reaction he got from his more conservative shareholders. “I lost a lot of sleep over that one.”

He shouldn’t have. Since Tricoire took over in May 2006, sales at the French conglomerate have risen 90 percent and earnings have more than doubled, to $2.5 billion in 2011. Tricoire has shaken up the internal culture at Schneider, a 130,000-employee company founded in 1838. It prospered with the rise of the global electrical industry.

With operations in more than 100 countries and a history of running its many product lines as separate busi- nesses, Schneider seemed practically impervious to change. The Paris- based company owns a profusion of brands, including Square D circuit breakers in the US, and sells thou- sands of items for industrial automa- tion and building management.

Many of its managers had built prosperous careers selling electrical equipment to outside distributors who had cozy relationships with their customers. There was little incentive for them to work closely with other Schneider divisions on marketing or to develop new prod- ucts designed to capitalise on the trend toward centrally controlled and monitored networks.

Luckily Tricoire had a mandate. The man who promoted him, former CEO and current chairman Henri Lachmann, “wanted to change things”, and was willing to look beyond France’s incestuous business culture. Instead of graduating from one of Paris’ top business schools, Tricoire earned a degree in electronic engineering from a college in Angers. He wasn’t a Schneider lifer, having joined it in a corporate acquisition in 1986. He’d spent most of his career on the field, including Italy, China and South Africa. “I loved operations, and I loved operations far from the headquarters,” says Tricoire. “I had no passion for corporate.”

One of Tricoire’s first moves after buying APC was to tell 20 Schneider division chiefs that their products would have to provide integrated electronic monitoring in the way APC controls the vast electrical demands at data centres. “Ten of them said no way, not with their product lines,” recalls Tricoire. “Those 10 weren’t with the company much longer.”

All 13 top executives at Schneider are Tricoire recruits. Average age? In the 40s. They are evenly split among the US, Europe and Asia, with Tricoire working out of Hong Kong. Next he pushed executives to develop a new marketing strategy based on energy conservation, again building off the experience at APC, which came to dominate the data-centre business by developing products, including cooling systems that adjust themselves to the demands of individual server racks.

Schneider poured money into software, including buying Telvent for $2 billion last year. The Spanish firm sells traffic-control systems, programs to cut energy usage in water utilities, and weather-monitoring software.

The strategy: Sell a combination of equipment and software that guarantees energy savings of 30 percent or more a year. “Everything is becoming monitored, controlled and more efficient,” Tricoire says.

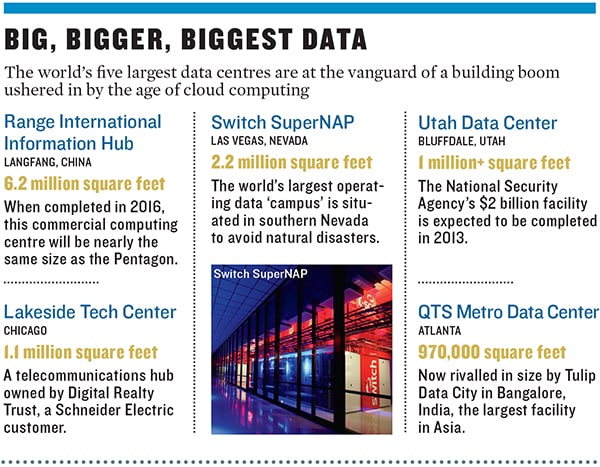

One of Schneider’s biggest new customers is Digital Realty Trust, an $8 billion (market cap) REIT operating data centres around the world. The shell of a data centre costs about $100 per square foot to build, but the electrical guts—much of which Schneider sells—can cost six times as much, says Jim Smith, Digital Realty’s chief technology officer. That includes uninterruptible power supplies the size of a delivery van—“We buy hun- dreds of them a year,” Smith says—as well as hundreds of electrical meters at $500 to $5,000 apiece. “That metering foundation is the source of all my telemetry,” says Smith.

With regulatory pressure increasing on energy hogs like data centres, the landlord with the best monitoring systems has the edge. Tricoire’s integrated approach is key. “If you knew the Schneider Electric of 10 years ago, it was a famously unintegrated company,” Smith says. “They’ve made great strides.”

Another Tricoire innovation was to hire Schneider’s first marketing chief. Aaron Davis, a Columbia Journalism School grad who joined APC in 1989, moved to Paris after Schneider bought the company. (Davis says his wife, who is French, recoiled when he told her about the acquisition: “Schneider? But they’re French!”)

Davis says Schneider has been successful with the first part of its transition, “taking a fairly endless supply of products and gadgets and simplifying them and consolidating them in portfolios.” The hard work is retraining a 20,000-strong sales force to sell collections of products that can be linked together with software to reduce energy consumption.

But Tricoire says he’s building a business to withstand change. Sales in Schneider’s traditional market, France, now trail those in the US and China, and revenue has more than doubled in China, India and Brazil over the past three years. “My job is making sure these transitions happen, and happen smoothly, and enable the next round of changes,” says Tricoire.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)