How lessons from the mafia helps Sheldon Yellen run a $1.5 billion business

The CEO of one of the world's largest disaster-cleanup companies built a $320 million fortune with a helping hand from reputed mafia figures years ago and management tactics straight out of The Godfather today

Like any good autocrat, Sheldon Yellen demands trust from everyone in his organisation while harbouring his own secrets Hurricane Matthew slammed into the Jacksonville area in Florida on October 7, 2016. Belfor employees arrived to start the cleanup as soon as the storm passed

Image: Brandon Schulman for Forbes

Less than a week after Hurricane Matthew sideswiped the southeastern United States in October, Sheldon Yellen stands in a wind tunnel next to a resort outside Jacksonville, Florida, imagining the scene of the storm. “Winds blowing upwards of nearly 200 miles an hour, water was crashing all the way to this hotel,” he says, wearing a bright-blue storm jacket, black slacks and a gold-chain necklace. “It didn’t appear to be that strong because it was 30 miles offshore, but you’ll see the damage. There’s millions of dollars of damage.”

Bad news for pretty much everyone here. Good news for Yellen, who runs the disaster-cleanup company Belfor Holdings. Operating on only a few hours of sleep, three days into a tour of coastal devastation, he guides me through the back door of the resort, which hired his company to clean up after Matthew. Inside, roughly 75 of Yellen’s workers from across the country have been drying out walls, replacing windows and repairing ceilings for days. Belfor employees started driving toward the hurricane when it was just a swirl on the radar out at sea, then rushed into the hardest-hit areas as soon as the storm passed, in some cases arriving before anyone but the police and the National Guard.

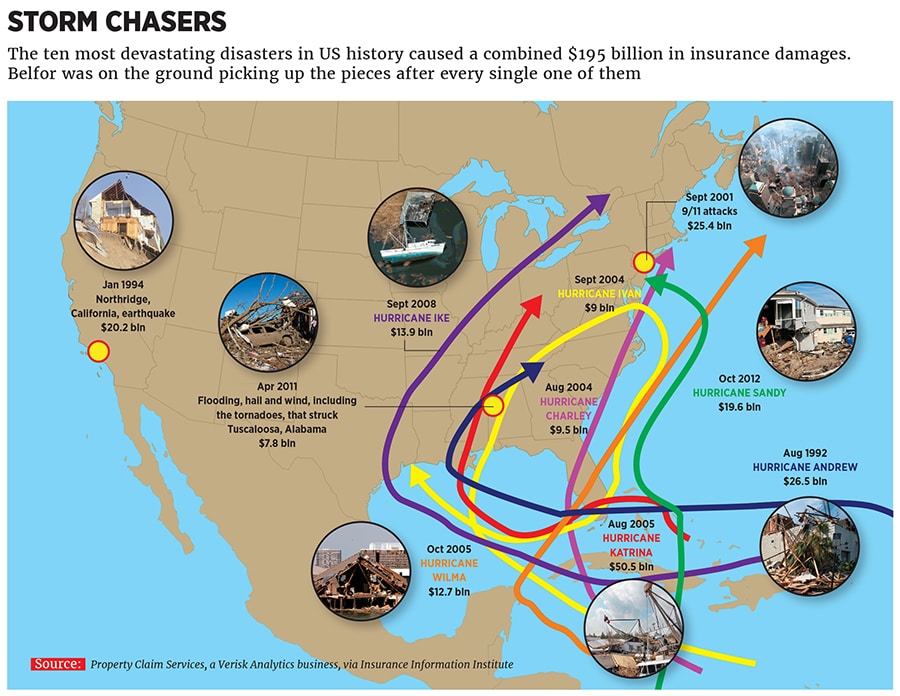

When disaster strikes, Belfor gets called in to do the dirty work. Over the course of its history, Belfor has cleaned up more than a million sites around the world, whether scrubbing dust-filled buildings after the September 11 attacks, fixing up 20 of New Orleans’s high-rises following Hurricane Katrina or collecting body parts in the French Alps after a deranged Germanwings pilot ploughed his plane into the side of a mountain two years ago. When it isn’t dealing with high-profile disasters, Belfor handles everyday messes like garage fires and basement floods. Its competition is fragmented: Mostly local cleanup crews in any given market, who lack Belfor’s experience and scale. Hence, when insurance companies or multinationals like Wal-Mart or General Electric have a big mess on their hands, Belfor tends to get the first call. Last year, the privately held company, based in Birmingham, Michigan, brought in $1.5 billion in revenue.

It’s low-margin work. The company says it netted less than 3 percent last year, as insurance companies constantly push down prices. But profits jump during hurricanes—climate change is good for Belfor—when there is plenty of work to do and not enough people who know how to do it. Forbes estimates that the company is worth $900 million and that Yellen has a net worth of $320 million.

It’s quite an accomplishment for this 59-year-old high school dropout, and one that has come as he’s harboured a professional secret for three decades. “I’ve been shot at, I’ve had a gun pointed down my throat, I’ve held guys at gunpoint,” says Yellen, who stands just 5-feet-6-inches tall, has a bit of a paunch and wears his hair transplant slicked back. “People don’t know that. I’ve never talked about that. I’ve done 30-some years of keeping that private.”

Eventually, he does talk, though, and in greater detail. His background. His mentors. His tactics. Many have chronicled organised crime businesses that have tried to go “legit”. Yellen has built a legit business—but the lessons that he all but admits came from mafia figures helped turn Belfor into a billion-dollar juggernaut.

Growing up, Yellen didn’t see much of his old man, who suffered from digestive problems, spent two years in and out of hospital and developed an addiction to painkillers. Michigan records reveal a list of drug convictions and prison sentences. “We thought he was a travelling salesman because he would show up every six months or year for a day or two,” Yellen says. “We would jump on his lap and want to throw a baseball with him, just like you would with your dad. And he would do that for a day. Then he would disappear again.”

In his absence, Yellen’s mom, Lenore, scraped by on welfare and put her sons to work. It still wasn’t enough: Yellen came home one day and found a local official warning his mother that they were facing eviction. He got his first job at 11, washing dishes at a hamburger joint for $1.10 an hour. Three years later, a family friend got Yellen a gig cleaning toilets at the elite Southfield Athletic Club in the Detroit suburbs, which counted some of the city’s most notorious mob figures among its patrons.

Not that Yellen likes talking about that. “I’ve worked for some Italian people that controlled a lot of turf,” he says cryptically at one point. When later asked about successful people from organised crime, he smirks and says: “You’re almost asking me to confirm that I was in that world. I’m not confirming that. I know I’ve lived two different lives, but I’m not confirming that was the life.” Yellen later flatly denies that he ever worked in organised crime, but after I interview former federal investigators, read stacks of court documents and mine thousands of pages of FBI files, it becomes clear that Yellen’s connections with reputed mob figures helped him climb out of poverty.

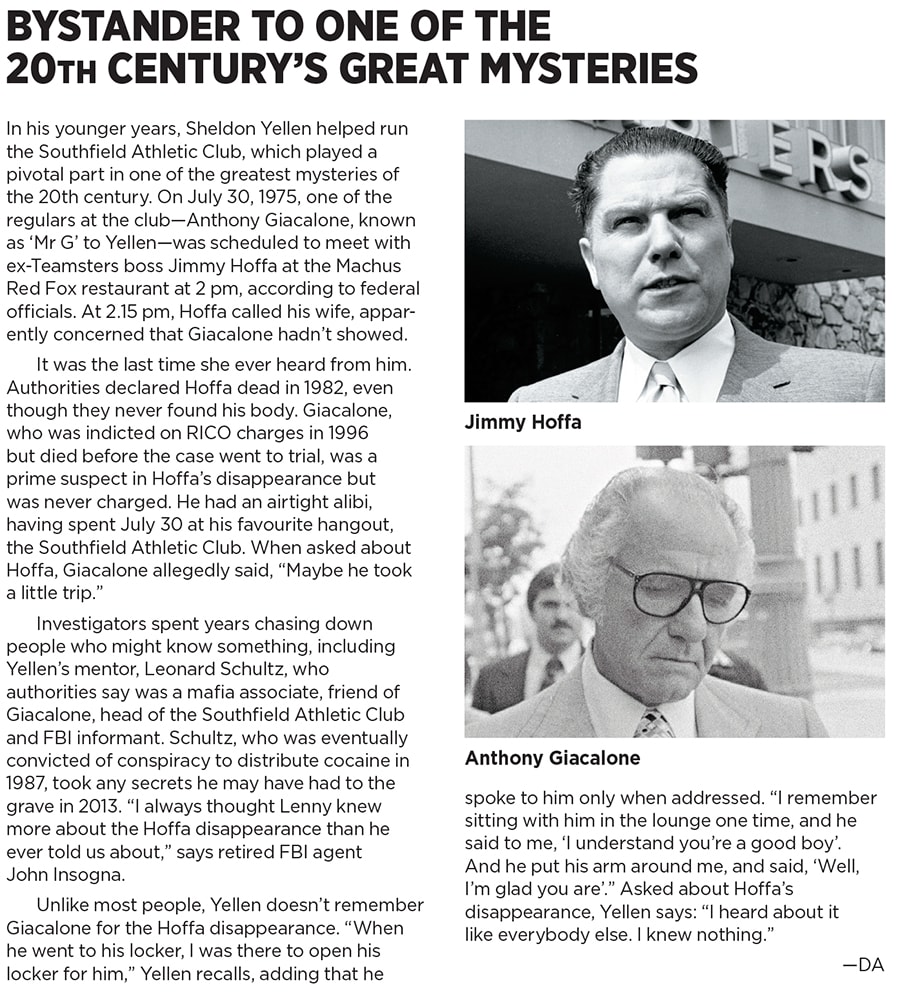

According to two retired FBI agents, the man in charge of the Southfield Athletic Club, where Yellen worked from age 14 to 22, was mafia associate Leonard Schultz. His sons also worked at the club. The place served as headquarters for reputed mobster Anthony ‘Tony Jack’ Giacalone, the mafia’s alleged street boss in Detroit who was long suspected of helping orchestrate the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa (see box, page 85). According to former FBI agents, Giacalone and his brother Vito (‘Billy Jack’) had hidden interests in a series of businesses throughout town, including a juice manufacturer named the Home Juice Co.

Yellen got into business with Home Juice after the Schultzes gave him clearance to run a juice concession inside the Southfield Athletic Club. This wasn’t any ordinary lemonade stand. “You would say big deal, you sold papaya juice. I was 17 or 18 years old, and I was selling thousands of dollars a week,” Yellen initially says. When subsequently pressed about whether those sales were all legitimate, he insists they were. Two weeks later, he calls unannounced and says that he misremembered the revenue figure—the juice stand was taking in only hundreds of dollars a week. Regardless, he is still thankful to Schultz, whom he calls a mentor. “Mr Schultz was good to me,” Yellen says. “I didn’t have a dad around. I’m not saying he was my surrogate father... but he took an interest in me.”

Not everyone remembers Schultz so fondly. Ultimately convicted of conspiracy to distribute cocaine in 1987, Schultz started regularly appearing in local newspapers around the same time Yellen opened his juice stand. Most of the stories centred on what happened on a cold March day in 1974 when Schultz invited a young furniture entrepreneur named Harvey Leach to his house for a meeting. It is unclear whether Leach ever arrived. The next day, authorities found him in the trunk of a Lincoln Continental with his throat slashed, according to local police records. Schultz was questioned by police but never charged. A lawyer connected to Giacalone eventually took over Leach’s furniture business, according to FBI files. The murder was never solved. Years later, it became public that Schultz had served as an FBI informant.

Around the same time, Schultz helped Yellen secure a line of credit to get started in the vending-machine industry, which former FBI agents say was heavily infiltrated by the mafia at the time. Yellen eventually built up a business of 100 vending machines and arcade games. At the time, the machines were worth between $600 and $2,500 each.

When asked what he had done to earn such a lucrative opportunity, Yellen starts shifting in his chair. “I um, I um—man,” he mutters as tears fill his eyes (he cried several times during my interviews with him). He sits in silence for 25 seconds, staring at the carpet inside the Florida hotel, shaking his head intermittently, then dodges the question. “I had a life on the streets,” he says. “I was exposed to things and to people, and I experienced being on both sides of the tracks for various reasons.”

The streets proved to be dangerous. One time, Yellen was collecting coins when someone opened fire on him. He started wearing a bulletproof vest and carrying a gun. The new tools came in handy when three people tried to rob him. “I had to pull out my gun,” Yellen says. “Having a gun pointed at three guys laying on the ground—‘Get on the ground. If one of you move, all three of you are dead’—that’s scary.”

Marriage provided him a way out of that life. When Yellen was 26, his wife’s brothers, Randy (a member of the Southfield club) and Mark Fenton, offered him a job at their family company, Inrecon, which did $5 million in annual revenue selling awnings and fixing up properties. Eager for a more stable lifestyle, Yellen accepted the offer and became Inrecon’s 19th employee in 1984.

He jumped into the property-repair side of the business, which relied on calls from insurance companies that needed to fix damaged buildings. As a young guy with no connections in the industry, Yellen found it difficult to get meetings with insurance agents. So he mapped out 120 insurance offices nearby and marched into every one. He had a standard opening line to the receptionists: “How are you? I don’t have an appointment. I’m not going to stay and talk to you. Here’s my card. I’ll see you in two weeks, same time. Goodbye.” He tracked the meetings in his notepads and showed up again two weeks later—same place, same time—and eventually became a familiar face to the insurance businesses, which started calling him when they had big jobs. By his second year at Inrecon, Yellen claims, he was bringing in nearly $5 million of business by himself, about as much as the rest of the company.

In 1989, Hurricane Hugo slammed into Charleston, South Carolina, causing $7 billion of damage. Sensing opportunity, Yellen’s brothers-in-law told him to grab 25 workers and start driving south. Along the way, he pulled into rest stops and offered a job to anyone with a pickup and a toolbox. Before long, he was trailed by a caravan of 30 trucks. “Every truck was more rusted than the one before it,” Yellen says. The night they arrived, there weren’t enough places to sleep, so Yellen crashed on the beach. He eventually moved his then-pregnant wife to South Carolina. He got some jobs, but the insurance companies delayed their payments, and Yellen couldn’t pay his workers. After one carpenter heard the news, he punched Yellen, who punched right back. It all paid off when the cheques started rolling in, eventually totalling $17 million, doubling the annual sales of the company.

After 18 months, Yellen moved back to Michigan. The break didn’t last long. Hurricane Andrew struck Florida in 1992, and Yellen again uprooted his family to move to the scene of the storm. He got into another cash crunch—this time an angry drywall installer pulled a gun on him—before the windfall repeated. Yellen landed $35 million of work during Andrew.

At this stage he wanted a piece of the action. He returned to Michigan, ready to tell his brothers-in-law that he was leaving to start his own business. But before he revealed his plan, they made him an offer: 10 percent of Inrecon for $500,000. When Yellen asked how he could possibly come up with that much money, they handed him a bonus cheque big enough to cover the cost. He bought in and became a shareholder in the business.

That kicked off a chain of deals that, over 13 years, created today’s Belfor. First, industrial giant Masco Corp bought Inrecon for about $90 million in a two-part transaction in 1997 and 1999. Yellen made an estimated $8 million in the deals; he and his brothers-in-law stayed on as employees. Masco then resold Inrecon to the German disaster-restoration company Belfor for an estimated $190 million in 2001. That’s when Yellen’s in-laws left, but he stayed put.

Trouble started brewing inside the business. In 2001, Belfor workers had rushed into Manhattan’s financial district after the World Trade Center attacks to clean dust out of buildings. Like so many first responders, they fell victim to toxic pollutants swirling around the site. Over the next five years, more than 100 plaintiffs filed lawsuits against Belfor, and it looked like the company might have to pay hundreds of millions in settlements. Belfor’s German owners, the Haniel family, wanted out—and Yellen wanted in.

Through a series of deals, he raised $322 million, the bulk of which came from JPMorgan and the Haniel family, which put up $150 million each. He persuaded dozens of colleagues to hand him a total of $22 million; many of them took out loans to finance their purchases. Yellen himself put in $8 million and lent employees another $4 million. Today he controls 95 percent of the voting power at the company, despite owning an estimated 30 percent of the business. It’s unclear who owns the rest—Yellen initially said there are 52 shareholders. Later his CFO said there are 55 before they finally settled on 60. One former shareholder says he has no idea. It’s hard to be sure, since shareholders don’t have yearly meetings, don’t get full financials and haven’t received a list of their fellow owners in more than ten years. “My initial reaction to the whole offering when it came out was: Do you trust these guys or don’t you?” says Rusty Amarante, a shareholder and top executive. “Because who would invest in something where they have no vote, no say—there isn’t anything I can do from a stockholder’s standpoint to influence the company.” There is technically a two-person board of directors, but when asked, Yellen says he doesn’t know who the other board member is; his chief financial officer tells him it is Bernd Elsner, the retired head of Belfor’s European operation.

What is clear: Yellen’s timing and luck couldn’t have been better. Shortly after the Germans told Yellen they wanted to sell, Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans, causing more damage than any other storm in US history. The deal still went through. He lucked out with the lawsuits as well. In 2011 and 2015, then US President Barack Obama signed bills to compensate 9/11 victims, which ultimately meant Belfor paid out just $1.5 million in legal fees.

Yellen likes to describe Belfor as “cultlike” and “a family”. Like any good autocrat, Yellen demands trust from everyone in his organisation while harbouring his own secrets. Not even Yellen’s brother Michael, the company’s chief operating officer and second-largest shareholder, regularly receives full financials (the CFO, Joe Ciolino, claims Michael can ask to see them at any time, though he can’t recall the last time he did). Michael and most other shareholders get a summary report once a year. Small stakeholders who were granted equity as part of their compensation receive nothing at all.

Ciolino says the original shareholder agreement warned investors that they would not get full financial information in the future. When some balked, he made it clear they could get on board or walk away. “You’re not going to get it,” he said. “You can ask for it. You’re going to get limited financial information. If you don’t want to do it, that’s great. But this is not a committee. This is an opportunity.”

How much people get paid is also a secret. Every January, Yellen, his brother Michael and Ciolino decide on bonus packages for the company’s top 350 managers. On average, 50 percent of their annual pay comes in the form of a bonus. But it’s all discretionary: If Yellen and his inner circle want, they can choose to pay no bonus at all. For the top ten employees, Yellen himself decides the size of the cheques. The vast majority of their compensation comes in a single payment, which is not disclosed to shareholders. (Yellen insists he takes only a small salary, though he won’t say how much it is.)

Yellen’s incentive plan sounds familiar to Greg Stejskal, a retired FBI agent who spent years chasing the mafia around Detroit. “It sounds like the structure is very much analogous to the way [the mob] set it up,” Stejskal says, from the secrecy to the complete authority of the leader, manifested in the lump-bonus payment determined at Yellen’s discretion.

There’s also a familiar amount of paternalistic benevolence. Yellen carries around a thick wad of cash, something Anthony Giacalone was known for back in the day, and doles out $100 bills on a whim. He handwrites birthday cards to all of his 7,400 employees every year (employees are quick to let him know when he misses one). On his wrist he wears about half a dozen bracelets, one for each of his employees’ children who has cancer. They are his pen pals, and when they get healthy, Yellen flies to wherever they are to cut off the matching bracelets on their wrists.

Of the 82 business owners Inrecon and Belfor have bought out over the last 27 years, as they’ve rolled up potential competitors, 68 are still at Belfor today. “There’s a tremendous loyalty to Sheldon,” says Pete Boylan, who sold his one-office operation to Inrecon in 1999 and now serves as a regional manager in the southeastern United States. “Sheldon is the type of guy, if you’ve got his back, he’s got your back.”

Until he doesn’t. During the cleanup after Katrina, a group of subcontracted workers sued Belfor, saying they laboured 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, without overtime. The parties eventually settled the case; Belfor agreed to pay all overtime wages but did not admit to any wrongdoing. In a separate case, an original investor who was later fired by Belfor, James Coleman, sued his former employer, alleging that the company offered him a paltry amount of money when he tried to sell his stake. They eventually reached a confidential settlement.

The code in the Detroit mafia was that there was no getting out. Once you were in, you stayed in. Yellen says he was days away from cashing out his own stake in the business a couple of years ago, after agreeing to sell Belfor to a private equity firm in what he claims was a billion-dollar deal. At the last minute he backed out, claiming he couldn’t bear to abandon his employees.

So Yellen’s in, he says, and on the verge of making his biggest acquisition yet, which will expand Belfor into a new but related industry. He won’t get into specifics but claims it will more than double the revenues of his company. Yellen sees the deal as a first step in turning Belfor into a diversified empire, with several giant businesses alongside its disaster restoration arm.

That will take a lot of work, and Yellen in turn predicts that he will eventually die at his desk, which he says is a far better fate than on the streets. “When you’ve been shot at, and you’ve had a gun held down your throat,” he says, “you don’t forget”.

(This story appears in the 30 November, 2017 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)