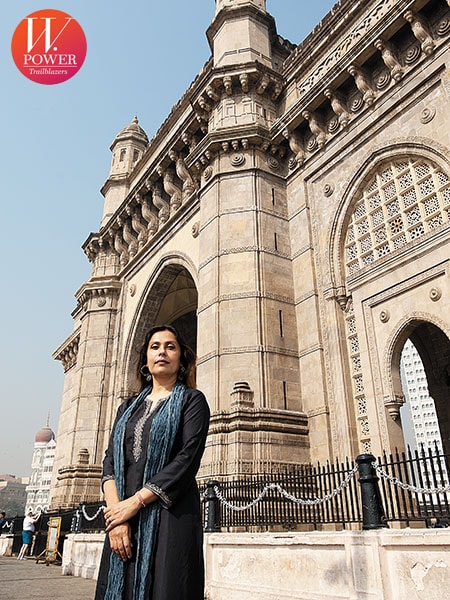

Abha Narain Lambah: Etching stories in stone

The founder of Abha Narain Lambah Associates brings back glamour to India's significant buildings in a profession that is anything but glamorous

Abha Narain Lambah

Age: 48

Conservation Architect

A few steps from Carter Road’s seafront, conservation architect Abha Narain Lambah’s office is elegant and characteristic. One wall is papered in a black-and-white vintage print of old Crawford Market, one of Mumbai’s iconic buildings that Lambah takes credit for restoring. Another wall is punctuated with neatly framed certificates written in calligraphy, the kind you would see at a decorated doctor’s office. This analogy continues into our conversation.

“You join architecture, as medicine, because you’re idealistic about making a difference,” says Lambah. “In conservation, you cannot come up with a formula and apply it to every site. The sites are as varied as a Buddhist temple in Ladakh or an assembly building designed by Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, or a posh palace in Patiala. You diagnose a building the same way a doctor diagnoses a human being. You first listen, read, see and understand it, and then look at how you are going to suggest interventions.”

2019 W-Power Trailblazers list

Lambah, 48, the principal architect and founder of Abha Narain Lambah Associates, has refurbished many of India’s historic buildings over a 25-year-career. You’ll find her invisible signature on the Ajanta Caves in Aurangabad; the 15th-century Maitreya Temple Basgo in Ladakh; the Golconda Fort, Charminar and Qutb Shahi Tombs in Hyderabad; the Bikaner House in New Delhi.

Based in Mumbai, she has worked on some of the city’s most prominent buildings as well, including the Bombay High Court, Asiatic Society Library & Town Hall, the BMC headquarters, the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya museum and the Royal Opera House, which has regained its splendour and status as a cultural hub since reopening in 2016.

Most recently, Lambah unveiled the refreshed Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue in Kala Ghoda, returned to its original colour palette and resplendent Victorian interiors. As the architect fields phone calls and messages through our conversation, it is apparent that she is enthusiastic about what’s next on her table: Returning the sheen to the towering Gateway of India and putting together the ₹100-crore-plus Bal Thackeray Memorial at Shivaji Park.

Lambah studied architecture at New Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture, and was fascinated by the monuments of the Sultanate period there. “A common story is that you get into architecture because you’ve read The Fountainhead and seen interesting buildings,” she says. “For me too, it was a question of ‘Why should Howard Roark be a male figure? Why can’t Howard Roark be a woman?’”

Throughout her education, Lambah was enamoured by architects like Joseph Allen Stein, an American architect who worked extensively in India. Stein had worked on the India Habitat Centre in New Delhi and other buildings, “which were contemporary, but held their own against historic monuments”. “It was my mission to work with Stein before he retired,” says Lambah with a smile. “I was the last architect to work there before his practice closed… he nudged me in the direction of conservation, recognising that I have an active interest in it. I wasn’t working to build my portfolio in that direction, or even thinking along those lines back then.”

The nudge was well-directed. In her long career, Lambah has worked with village councils and royal families, politicians and storied colleges, but has shied away from taking up assignments for private homes or doing interiors for rich clients. “I’ve never been spurred by that,” she says. “I would rather take up a challenging project that deals with streetscapes—through historic towns like Jaipur, or the Fort area in Bombay, even Kanchipuram. I want to have made at least one city better than I saw it, or be able to keep something that is precious from decaying or disappearing.”

Conserving a historic building is a sensitive job, one that involves taking on the onus of telling a version of history. Many of the structures are decrepit and dangerous, having been vacant and ignored for decades. “Fortunately, I’ve had no accidents yet, but I’ve had recurring nightmares,” she says. “When I had taken up the 15th-century Maitreya Buddha temple in Ladakh, I would wake up sweating, imagining the whole building caving in on me. I was dealing with a centuries-old fragile mud building, which was already on World Monuments Fund’s watch list of the 100 most endangered sites of the world. I was so scared that nothing I do should damage it in any way.”

The project was also particularly difficult—Lambah recalls working in sub-zero temperatures without electricity or telephones, and without proper toilets—just a mud hole in the ground. “Equally challenging was working in 46° Celsius heat in Hampi, getting a conservation site going. I think the buildings look glamorous at the end of the day, but the profession is anything but,” she says.

It’s been 13 years since the Ladakh project was completed. “An architecture professor of mine would always say that after a project, if your client and you can have a civil conversation over coffee, it means it was successful. Thankfully, the King of Ladakh and I have turned out to be the best of friends, so I’m pleased with how that turned out.”

It took 10 years to find a sponsor for the restoration of the Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue in Mumbai

It took 10 years to find a sponsor for the restoration of the Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue in Mumbai Image: Mexy Xavier

India has a poor archival programme, which means Lambah and other architects have few references to work with when determining a building’s original appearance. The Royal Opera House, for example, had been converted to an art-deco, single-screen cinema hall for decades before it closed down, and there were few allusions to its earliest opera-theatre avatar.

“Out of the blue, I got an email from a professor teaching theatre in Australia who had come across this opening catalogue of the first show at the Opera House—a black-and-white pamphlet,” Lambah recalls. “It was so interesting because we were then able to recreate the side balconies and the final finish was completely validated by the old photographs.”

“Abha’s exemplary work while restoring the Royal Opera House ensured that it glitters as brightly as it once did,” says Maharani Kumud Kumari of Gonal, the erstwhile royal family that owns the city opera house.

Sometimes, on peeling back layers of paint, the building reveals itself—as in the case of the synagogue and the BMC headquarters, where Lambah’s team found the original colour palette and stencil bands of motifs obscured under the layers. At other times, “you have to rely on oral tradition,” says Lambah. “In the case of the Moorish Mosque, Kapurthala, my greatest source of information was the grandson of Maharaja Jagatjit Singh, a brigadier, Sukhjit Singh. He remembered from his childhood the colour schemes, materials, even missing chandeliers. He led us to find the chandeliers locked away in storage.”

For projects in Ladakh, Lambah sought the help of old craftsmen, who, in their 90s, remembered the right mix of clays for different parts of the building.

Glass ceiling

Architecture—especially conservation—has been male-dominated in India, and Lambah has worked to define her own rules. Mary Woods, an American professor and author of a book called Women Architects in India: Histories of Practice in Mumbai and Delhi, recalled an anecdote that Lambah shared with her during her research, in an interview to Mumbai Mirror. “Once, when Abha was working on one of her restoration projects, she was encountering not outright resistance but passive opposition,” Woods told the daily. “Things really changed when she climbed the bamboo scaffolding in her sari. It was almost as if they were daring her to do that, a way of physically testing her resolve.”

“I’ve never been a conformist, so my gender has never got in the way,” Lambah says. “I’ve done some admittedly bizarre things—my daughter has grown up on sites, for instance—and clients have accepted it. You have to push the envelope and find things that work for you. If I said I have a child and I can’t take her to site and, therefore, I’ll stop working, that would be a choice I was making. But I chose to take her to site, and as a result, I never really took a break. My entire maternity leave was exactly 20 days at my mom’s place in Delhi. I flew back with my daughter and went straight for a meeting with the Horniman Circle Association.”

“Abha has had to operate in a world that’s dominated by men’s influence, and her journey has been remarkable,” says architect and urban planner PK Das. “She is not only adept at the planning and designing, but also in making sure that her projects see implementation all the way through.”

Implementation isn’t an easy task. For instance, with the Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue, it took 10 years to find a sponsor for the restoration as most are wary of touching religious institutions. Eventually, Lambah and the synagogue team found a partner in the JSW Group conglomerate’s Sangita Jindal. The group financed most of the ₹5 crore project. “Considering we have such a vast heritage and a hugely under-funded conservation programme, we need to look at better financial mechanisms—what kind of economic incentives we can give to privately-owned heritage, how to disincentivise the demolition of old buildings,” says Lambah.

“We talk about recycling energy, water, paper, but recycling buildings would actually create a much bigger green impact, considering the energy that goes into constructing a new building,” she adds.

Finding funds is a challenge, especially for non-governmental buildings, she says, adding that India could look to other parts of the world for lessons in best practices. England has a national lottery fund that releases money for conservation each year, regardless of whether the buildings are owned by the government. In places like Venice, many tax breaks and credits are offered if you help restore a historic building.

“We also need to stop thinking in a monument-centric manner, but think in terms of streetscapes,” she says. “The public realm of a city is defined by what you see as a whole historic neighbourhood, not just one building that’s beautiful, when the rest of them are falling to pieces, or full of new glass and aluminium.”

Mumbai, she says, has the most fabulous groups of buildings, as in the art-deco sweep, or the buildings along Princess Street, which, unfortunately, lie decrepit and messed up with bad signage. “Ballard Estate is no less in terms of beauty than Paris… a bit of maintenance, illuminating them at night, keeping the facades clean of additions and alterations could make a huge difference to the way people perceive the city.”

Lambah’s one unfinished dream is to restore a significant building in Kashmir, where her mother’s side of the family comes from, and where she spent many childhood summers. “I’ve always had a deep desire to work in Kashmir, given my obvious connection to it. In my head, I’ve identified all the buildings there I could work on. We’ve been shortlisted for a project there. But until we clinch the project, I’ll remain waiting.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)