Meet the Box Office Badshah you didn't know: Sajid Nadiadwala

With a strike rate of over 95 percent, Sajid Nadiadwala is arguably the most successful producer in Bollywood

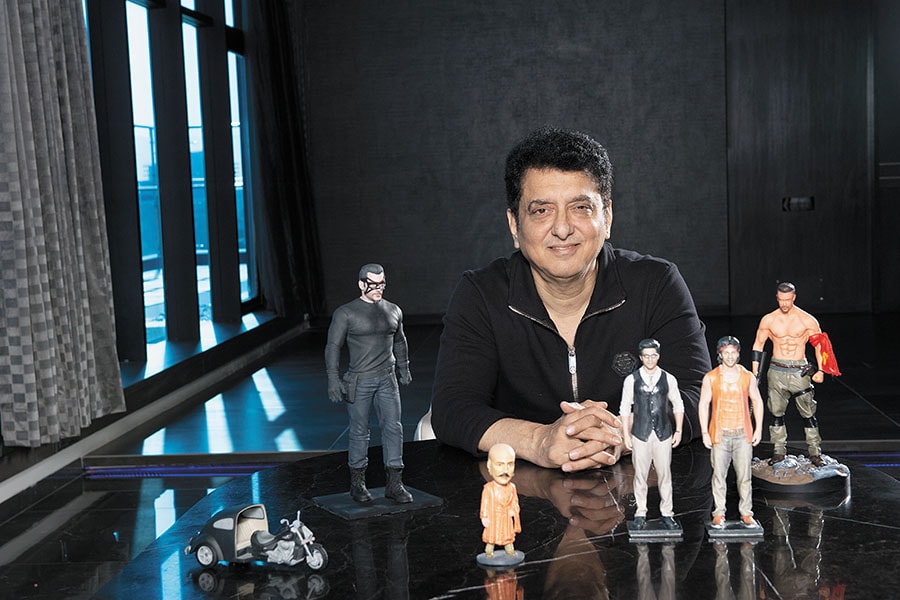

Producer Sajid Nadiadwala gives his directors the freedom to make movies the way they want

Producer Sajid Nadiadwala gives his directors the freedom to make movies the way they wantImage: Mexy Xavier

Liberty Cinema, Mumbai, 1997. It was February 6, a quiet Thursday night. There was no queue for tickets outside the theatre in Marine Lines, South Mumbai, for the 9 pm show—the last before blockbuster Friday, when new films hit the screen.

Inside the cinema hall, the dark hid the empty seats. Sajid Nadiadwala, dressed in his favourite black T-shirt and blue jeans—was getting fidgety. The 30-year-old film producer had organised a private screening. The film was Judwaa, his fourth under Nadiadwala Grandson Entertainment (NGE), which debuted in 1992 with Waqt Hamara Hai.

Sitting next to Nadiadwala in the last row were six friends, including a distributor. Throughout the film’s running time of two-and-a-half hours, the buddies remained mum. After the screening, they looked pensive. “Picture theek hai (The film is okay),” deadpaned one of them. The grandson—that’s how friends addressed Nadiadwala because his grandfather AK Nadiadwala dabbled in production in 1948—sensed that they were trying to be polite.

The stocky film distributor, dressed in all white, couldn’t help himself, and moved his hand over Nadiadwala’s head to express sympathy. “It seemed as if they were at a condolence meet,” recalls Nadiadwala. Judwaa, he thought to himself, was meant to be a comedy, but there was not a peal of laughter from any of the six viewers in those two-and-a-half hours.

The unforeseen reaction took him into flashback mode. Two years back, a newspaper hack had taken a dig at Nadiadwala’s decision to make a movie with Salman Khan, because of the rough patch that the actor was going through. “Ek Salman toh chalta nahin, Nadiadwala has taken two Salmans,” (One Salman doesn’t work, and he has taken two),” was the jibe, alluding to the double role of the superstar in Judwaa. For a fledgling producer, especially after the last hit movie under his banner, Jeet, the prospect of a flop was disastrous—not just a fall of face, but a financial farce, too, what with debt repayment looming large.

The next day, grandson sneaked into Liberty theatre for the show at 11 am. It didn’t take long for his nervousness to make way for relief. And unfettered joy. The audience was on a laughter ride; the songs, especially 'Chalti hai kya 9 se 12', were cheered; and Salman Khan was the darling of the gallery. Nadiadwala stayed back for the subsequent shows, and nothing changed. Judwaa was on its way to becoming a superhit.

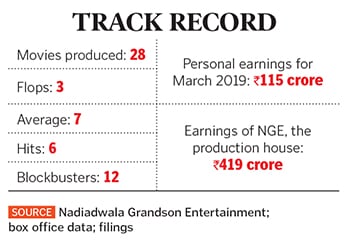

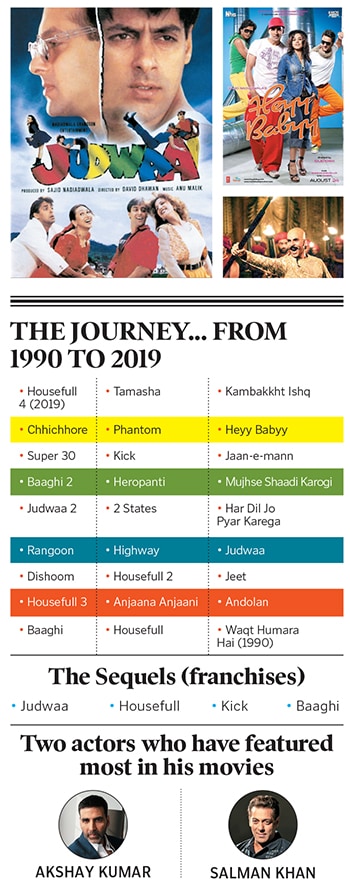

For Nadiadwala and his NGE, there has been no looking back since then. Twenty-seven years, 28 movies, 12 blockbusters, six hits, seven with average collections, and three flops: NGE, under the third-generation producer, has arguably emerged as India’s most successful producer, with a success rate of 95 percent. For the March-ended fiscal 2019, while the personal earnings of Nadiadwala stood at ₹115 crore, his production house posted revenues of ₹419 crore.

These days, Nadiadwala is no longer wary of failure; what keeps him awake at night is success. “Success,” reckons the entrepreneur, “has destroyed more people than failure. So one has to be careful.” That does sound cryptic, and Nadiadwala goes on to explain: Once you achieve success, there is a high possibility of failure lurking around the corner. And that’s because you might try too hard to replicate success. The antidote? Make a ‘nice’ movie. “When we want to make a hit film, it will be a flop,” he laughs. “A hit will happen if it’s nice. Let Friday decide that.”

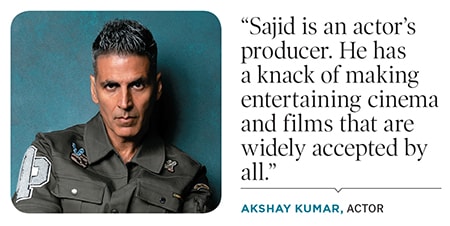

A nice film can mean many things. For Nadiadwala, it includes roping in a superstar. Akshay Kumar, Nadiadwala’s Man Friday—the other is, of course, Salman Khan—points out that the producer's biggest asset is his quality to stand by actors. “Sajid is an actor’s producer,” says Kumar, who featured in NGE’s first movie, Waqt Hamara Hai. Subsequently, Kumar teamed up with Salman Khan and Nadiadwala to churn out hits such as Mujhse Shaadi Karogi, Heyy Babyy and Housefull. The knack of making entertaining cinema, Kumar explains, is what makes him stand out. “He makes commercial films that are widely accepted by all audiences.” The attribute of striking a personal rapport with actors, Kumar reckons, makes him one of the most genuine and warmest producers in the industry.

Cut to Andheri (West) in Mumbai. On a warm, late-November Friday, Nadiadwala—dressed in his trademark black shirt and blue jeans—sinks into a plush red chair, reminiscing about his journey as a producer. The journey, he lets on, was not easy. If one thinks that anybody with loads of money can turn producer, then one is living in a fool’s paradise. “If you are only investing money, you won’t be able to survive for more than 10 years,” reckons the 52-year-old qualified chartered accountant and lawyer by profession.

What one definitely needs to survive after turning producer is a kit of must-have medicines. “Ask any producer, they will have anti-stress and calmers in their pockets and drawers. Even I have a few,” grins the grandson, who once aspired to become an IAS officer. Though he prepared for the competitive exam, he flunked badly in the subject that he thought he had mastered: Languages. Subsequently, he decided to try his luck in movie production. He first assisted filmmaker JP Dutta in Ghulami, before joining his uncle Habib Nadiadwala in the production business. The job was not glamorous. From making tea and coffee on the sets to procuring food and ice for the production staff and even driving cars to drop the actors, young Nadiadwala did everything. His accounting skills came in handy as he started taking care of the finances, and the legal background added heft to his reputation of fixing tough situations. “All my actors used to call me grandson,” he smiles.

Emboldened by the pace at which he was acquiring different skills, Nadiadwala plunged into production as an independent producer for the first time in 1989-90. The movie was Zulm Ki Hukumat starring Dharmendra, and the inspiration was The Godfather. “I am a big fan of Mario Puzo,” he says. He, however, found few fans for his maiden venture... it didn’t do well. The first two movies under his production house—Waqt Hamara Hai and Andolan—too didn’t set the box office on fire. Production, as Nadidwala gradually discovered, was not a cakewalk. The job, he reckons, is much more than money. Unless one has the knack to read the pulse of the audience and crack a successful entertaining formula, one won’t be able to survive. “We are the only company that has lasted over 65 years,” he says proudly.

The sense of history, legacy and wisdom gets magnified when one looks across the window of the 21st floor of the NGE office in Andheri (West), Mumbai. The grand aerial view of Veera Desai Road and the suburbs presents a contrasting picture to the magical grandeur that the producer has added to his corporate office, which is spread across three floors in a 22-storey building. A gigantic TV screen runs scenes from his latest movie Housefull 4, the fourth of the successful franchise that first hit the silver screen in 2010; there are miniatures of Salman Khan, Tiger Shroff and Varun Dhawan, and a bubblehead of Akshay Kumar. A shelf of his expansive personal room is dotted with trophies and awards.

While the booty has grown manifold, the formula remains constant. “I make movies for entertainment,” he says unapologetically. Although Nadiadwala has experimented with diverse content that won him critical acclaim with films such as Highway and 2 States, one genre the gritty producer contends he will never experiment with is dark movies. “It’s already dark inside the theatre. Why should I make a dark movie to make it even darker,” he laughs. The slapstick humour helps to reinforce the message that he will continue to play to the gallery.

The reason for sticking to the tried-and-tested format is not hard to fathom. Nadiadwala’s success formula of entertainment has held him in good stead and paid rich dividends over the last few decades. “I have never seen red on the balance sheet since 2000,” claims Nadiadwala, who also donned the hat of a director with Kick. The director, though, knows where to draw the line when he turns producer. “I never cross my line. If there are directors like Kabir Khan or Imtiaz Ali, I don’t enter the editing room without their permission,” he says.

Nitesh Tiwari, director of the blockbuster Dangal, contends that the freedom that directors get from Nadiadwala is what helps them give their best. “It’s natural for any producer to have inputs in a film. But he knows where to draw the line,” says Tiwari, who directed the Nadiadwala-produced Chhichhore. Though he gave his inputs on a few occasions, the decision to incorporate or reject them was left to the director. “He told me a simple thing: Take care of the film in the manner you want and leave the rest to me,” he says, adding that the unconditional backing of a producer who also knows direction is a big blessing. “His tremendous box office record is testimony to his knack of picking up stories that can be sold,” he adds.

Nadiadwala, for his part, says he will continue to back entertaining stories. “You are known by your last film. So you can’t rest on your legacy,” he says. The realisation of an uncertain future is what keeps him on his toes. “I’m always scared (of failure). This keeps me alive.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)