A Model for the Newborn

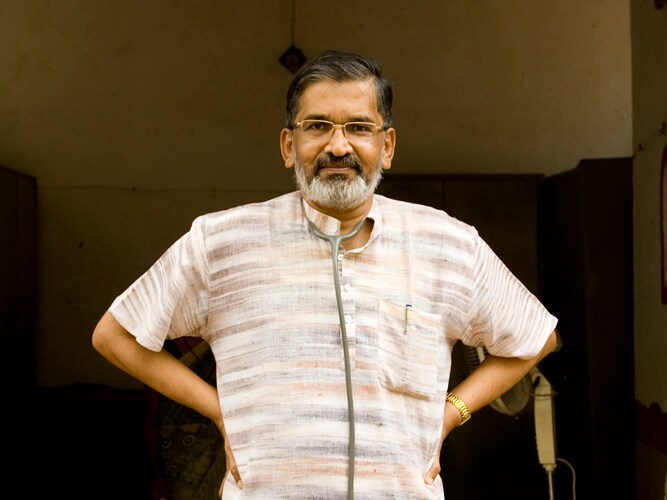

Dr. Abhay Bang has achieved a dramatic decrease in infant mortality rate by empowering local women with the knowledge they need to take care of babies

How did you come up with the Home Based Newborn Care model?

When we came to Gadchiroli [in 1984], soon after it was carved out as a new district, there was just one district hospital. To say that a baby needs to travel 300 kilometres for a hospital each day is to say let [it] die. The infant mortality rate was 120/1,000 live births. There was a sense of fatalism among parents. So we started teaching village women to treat newborn babies. Even now, 21 lakh children die before five and of them 11 lakh die in the first week. Neonatal mortality is also the most resistant to come down. So we decided to train literate village women. That was the hardest part — moving newborn care from hospital to home. We found that the major reasons for neonatal deaths were asphyxia, preterm births, infections and other reasons.

Was it hard to teach these women to administer injections?

For Sepsis, which was a major killer among newborns, we taught the women to identify seven major symptoms and said that if any two were there a diagnosis of Sepsis was made. It was an ethical and moral dilemma to teach these women to give Gentamycin injections to treat Sepsis. But once these symptoms become clear a baby can die within two days.

Then we called some top pediatricians from around the country to see our methods and meet our workers. The then head of pediatrics from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences said that these women were better at what they do than his students.

When we published research we found that these women detect Sepsis better than neonatologists in Boston. Treating Sepsis really built trust in these women because people in the village started seeing that they could save lives.

These women don’t know a lot of things but what the five things they do know they are perfect at.

It seems training and evaluation are key to making this work and scaling it. Can you talk about how you ensure that?

We trained these women in such difficult tasks by breaking it down to small bits and constantly supervising and retraining them. We train them through workshops and seeing deliveries with an Arogyadoot for around one year. There are evaluations after every workshop and at the year end. We have also made the selection process hard. That is why most of the women who started with us 15 years ago are still there.

We constantly monitor them through supervisors, who visit every few days and check their records. Their pay is deducted for not following basic procedures. For instance, if they don’t attend their pay is deducted. Earlier, just 50 percent attended childbirths. It is hard because it is often in the night and long drawn. But with performance-linked pay, more than 80 percent now attend. The record also functions as a friend to her and guides her through newborn health. It also acts as a quality control tool for the supervisor. So training, supervision and selection is key to this.

This is being taken to different states now where Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) will implement it. Do you think the ASHAs can be as effective as your Arogyadoots?

I am also very hopeful about the new cadre of ASHA volunteers the government has created. Imagine what we could do with half a million such women across the country. We need to have better trained ASHAs and give them more of a role and more responsibilities. We need to train ASHAs the same way we train doctors. Currently, they are being used as a social sales agent for government schemes.

What other issues do you see in scaling this up? What will your involvement be?

In replicating this model in other states, we have had some issues. For instance, in Rajasthan women observe purdah and wouldn’t move around much. In Chhattisgarh, they have a cadre of tribal health workers called Mitanin. Some of them are illiterate and it will be a challenge to teach them to administer injections. So we are thinking about what to do about this.

For the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) trial, the trainers came here for a 36-day training and then trained their volunteers. Now the planning commission has recommended the Home Based Newborn Care (HBNC) model for implementation. We will train and support states that implement it. The government has a goal to halve IMR by 2012 and HBNC is the only way to do that. It is also the most cost-effective. HBNC costs around $7 for every life year saved. Volunteers spend around 1.23 hours [83 minutes] a day on this work. On the day of a delivery, they could spend up to seven hours.

I believe this is being taken abroad too?

Now Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan have done pilots of this model. In Nepal, they focussed on other things. In Bangladesh, IMR reduced 34 percent in two years; In Pakistan, it went down 28 percent. That is because in Pakistan, it was administered through government employed women health workers, called Hala. They have a fixed pay and get no extra incentives for this. Several African countries have also started pilots last year. Results are awaited from the field trials in Zambia. I feel the need for HBNC is great there because IMR is high and they have an acute shortage of doctors.