Stephen Ross: The Last Master Builder

Stephen Ross is putting his billions, and his legacy, on the line to fix Manhattan’s West Side—and prove that private developers can still profitably transform the urban landscape

Staring across Manhattan’s last untamed strip, the rows of sleek silver commuter trains sliding along the island’s only active rail yard, the Related Companies’ Stephen Ross points to the future.

His finger moves faster, toward the eventual home of 6 million square feet of sparkling office space, divided between three towers; toward 5 million square feet of residential space, a mixture of affordable housing, luxury rentals and high-end condominiums; toward 1 million square feet of retail space, including a movie theater and a department store. He gestures at the future home of the hotel, the public school, the 14 acres of parks and open space. All on a 26-acre platform over a working rail hub. From scratch.

If he can pull this off (current estimate: Ten years and at least $12 billion), Hudson Yards will become the most significant private development project in Manhattan since John D Rockefeller Jr spent $250 million (more than $3 billion in today’s terms) to create the 22-acre Rockefeller Center in the 1930s, expanding and recentering America’s largest and densest city. “We are revitalising an area of our city that had long been underused,” says New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg. “When it’s complete, it will be one of New York City’s great neighbourhoods.”

In some ways, the stakes are even higher than that. Ross may own some 60 percent of Related, which currently owns and manages a property portfolio valued at $15 billion, but the Hudson Yards transcends money. Using every real estate trick he’s learned over his 71 years, Ross is trying to demonstrate that even in a hub of unions, regulation and bureaucracy, private developers can still accomplish grand things.

“When you look at the rail yards today you have to have vision,” he chuckles, watching the trains during a blustery Friday in February. “A lot of vision.”

Nestled against the Hudson River, Hudson yards' once-thriving shipping piers had no ships—New Jersey now hosted the port—and the once-teeming garment district to its south had few garmentos. In the 1980s the Metropolitan Transit Authority carved out train yards but also had the foresight to construct them in a way that would one day allow for platforms and buildings over the open-air tracks.

When Bloomberg took office in 2002, he came with an idea that seemed recession-proof: Bring the 2012 Olympics to New York City and put the Olympic stadium on the Yards.

A coalition quickly developed: Bloomberg’s economic development deputy Daniel Doctoroff led the Olympics effort; Ross would develop the surrounding real estate; the New York Jets, led by a new president, Jay Cross, would help finance the $2 billion stadium, which the team would use after the Olympics decamped.

Unfortunately for them, New Yorkers weren’t particularly keen on paying for a congestion-inducing football stadium, and state politicians voted down the project in 2005. The Olympics went to London just in time for the global financial meltdown.

Olympic failure, however, generated a commercial by-product. Bloomberg had already proposed a $2 billion subway link to the area, as well as a tree-lined boulevard between 10th and 11th avenues—people in theory would be able to get to the area and possibly want to stay. Equally important, he had muscled through rezoning to allow development in this “last frontier available in Manhattan,” as the city’s planning department has referred to the far west side of the island. “The office market in midtown was becoming tight,” says Corinne Packard, a real estate professor at NYU who once helped lead the city’s Hudson Yards efforts, “and there was worry that because prices were sky-rocketing firms were leaving the city.”

New York’s largest commercial real estate developers placed bids to develop it: Brookfield Properties, Extell Development, Tishman Speyer (with Morgan Stanley), the Durst Organization partnered with Vornado Realty Trust—and the Related Companies. Related had secured News Corp as its anchor tenant (earning its proposal the nickname “Murdochville”), but the night before the second-round bid was due, the media giant pulled out. Ross yanked his proposal, and Tishman Speyer ultimately won the bid.

Two months later the deal fell apart, and on Thursday, May 15, 2008 the MTA put the land back up on the block. Ross, smarting from the loss, lunged at the opportunity. The company enlisted Goldman Sachs as an equity partner and placed a new bid, sans anchor tenant. “We essentially moved into the office and didn’t leave until the deal got done,” recalls Jeff Blau, the president of Related Companies and Ross’ right- hand man. By Monday morning a press conference announced the new deal: $1 billion for a 99-year-lease. The timing couldn’t have been worse. Four months later Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, credit markets seized and the bottom dropped out of the real estate market. Related, due to formally sign the lease, got an ex- tension. “We spent all of 2009 getting the property rezoned and getting the details in place with the MTA—behind-the-scenes work we had to do anyway,” says Jay Cross, the former Jets president who Ross recruited to lead Related’s Hudson Yards initiative after the stadium project collapsed.

And it got worse still. Goldman Sachs pulled out as a partner in early 2010 just as the MTA began hammering Related to sign the lease. As the World Trade Center redevelopment, funded by 9/11 insurance proceeds and government agencies, began rising downtown, timing seemed to doom Ross to the same fate as the other developers who had tried to improve the choice parcel over the past few decades.

And it got worse still. Goldman Sachs pulled out as a partner in early 2010 just as the MTA began hammering Related to sign the lease. As the World Trade Center redevelopment, funded by 9/11 insurance proceeds and government agencies, began rising downtown, timing seemed to doom Ross to the same fate as the other developers who had tried to improve the choice parcel over the past few decades.

But Ross, aware that his window was closing, got creative. First, he replaced Goldman with Oxford Properties, the real estate arm of a Canadian pension fund, convincing them a 40 percent ownership stake was worth funding 50 percent of the project. Then he renegotiated an unprecedented lease with the MTA, which was as desperate to forge forward as Ross. Rather than extend the time window yet again, the two sides mapped out three economic triggers—an 11 percent fall in Manhattan’s commercial vacancy rate, residential prices hitting $1,100 a square foot and increasing construction activity—that would all have to click into place simultaneously for the lease to take effect (it hasn’t yet). Sweetening the deal further: Ross has the option to buy the land under each building at market value as they are completed. Rather than miss his opportunity, Ross can now push forward with confidence, knowing that his lease costs don’t kick in until the economy can justify it—and that within 10 years he can own a majority share of the 26-acre tract right down to the streets. “It is an unusual deal,” says Jeffrey Rosen, director of real estate for the MTA. “But this site is hardly typical.”

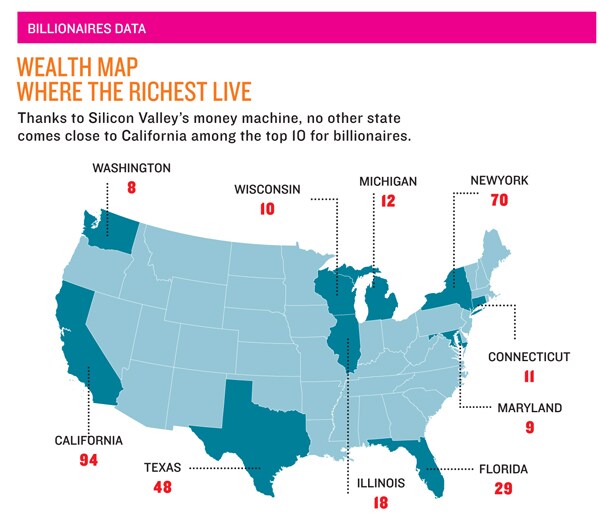

Nothing about Ross’ real estate career is typical. One of the richest developers in New York (net worth: $3.1 billion), unlike hometown boys Donald Trump ($2.9 billion) and Jerry Speyer ($1.7 billion), he grew up far from the Big Apple. His mother was a Detroit homemaker, while his father was an inventor, tinkering with vending machine coffeemakers and finding little financial success. For a business role model, though, he only needed to look to his uncle, oilman Max Fisher, a 23-year member of The Forbes 400 until his death in 2005. “When you can see someone like that, growing up,” says Ross, “it gives you the confidence that with hard work things can be accomplished.”

He picked a local college (University of Michigan, now home to the $100 million Stephen M Ross School of Business) and law school (Wayne State) before settling in downtown Detroit for a career as a tax attorney. Nonplussed by the prospects for his hometown post riots and his career path, he moved to New York City to try Wall Street. While he didn’t like that career either (he was fired for talking back at his second job), he liked the opportunities presented by America’s commercial capital. Armed with a $10,000 loan from his mother, the young transplant jumped into the one area of real estate where a strong New York family name and copious amounts of capital weren’t necessary to get started: Affordable housing. It was almost 100 percent government financed and, thanks to his tax background, he was able to drum up more money syndicating and selling the tax shelters that accompanied the projects to wealthy investors.

By 1980 he had built 5,000 affordable housing units. That same year his fledgling company teamed up to develop a tract on Manhattan’s East Side, Riverwalk. Ross’ name hit the front page of the New York Times, and he was off and running. Over the next 18 years he expanded into office development, then market-rate housing, retail development and, in 1996, his first major mixed-use development project, in West Palm Beach, Florida (Ross’ Florida roots got deeper in 2009, when he bought the NFL’s Miami Dolphins.)

Two years later the opportunity came to develop Manhattan’s Columbus Circle, another troubled Manhattan site with a long history of failed development attempts. Ross moved aggressively to secure an anchor tenant—he requested a meeting with Time Warner chairman Richard Parsons.

While he received just five minutes—Parsons had already been approached by eight other developers looking to partner with his company in a bid for Columbus Circle—he made them count. “Stephen said to him, ‘This isn’t about real estate; it’s about showcasing your brand,’ ” recalls Blau.

Within 24 hours Parsons and Ross had a tentative deal in place for the new $1.7 billion Time Warner Center, financed with the biggest loan for a non-government-funded project in commercial real estate history ($1.3 billion from GMAC, the former financing arm of General Motors). Ross won’t say what Related reaps from the deal, but within four years of opening, retail rents in the neighborhood spiked 400 percent, and 40,000 shoppers a day visit the building’s luxury shopping centre, making it one of the most successful malls in America. To celebrate, in 2005 Ross claimed for his own a $30 million, 8,300-square-foot penthouse in one of the towers, with panoramic views of Central Park and the city beyond.

Hudson Yards dwarfs the Time Warner Center—it will require four times the debt, and it doesn’t have the marquee anchor tenant in place. Related will ultimately put up 5 percent of the entire cost, or $600 million, supplemented by equity from Oxford Properties and eventually secondary investors. “It’s Time Warner on steroids,” says Ross.

The challenges are daunting. Before all the buildings can join Manhattan’s skyline, Tishman Construction, the master builder for the project, will stretch 17 acres’ worth of roughly 6-foot-thick steel-and-concrete platforms over the train yards—without disrupting service for more than 300,000 New Jersey and Long Island commuters a day.

That funding hinges on acquiring tenants, whose transactions will foot the majority of that bill. “You need critical mass, since we have to spend a lot of money on infrastructure early on,” explains Cross. “We need to create big [office space] transactions now to balance the investment in infrastructure with the ability to bring space online quickly.”

Compounding that challenge: 1 World Trade Center, the 105-floor megatower rising at Ground Zero 3 miles to the south, which will open next year.

When it does, 2.6 million square feet of brand-new office space will hit the market—backed by more than $6 billion in government tax breaks and other financial enticements needed to lure corporate residents to a site with such a tragic history (and distance from midtown commuter hubs). The powerful Port Authority of New York & New Jersey, which owns the building, even picked up the tab for the final years of Condé Nast’s midtown lease just to ensure it would move—part of a $47.5 million sweetener Related’s privately funded venture couldn’t possibly match. Sixty percent leased, 1 WTC still has more than 1 million square feet empty, about the same amount that remains unfilled in the first of Related’s two high-rise towers.

Ross is countering with an unheard of deal for New York’s commercial tenants: The option to either lease or buy their space—at cost. In other words, Related and Oxford will not turn a profit on the office space but rather will use their tenants as de facto lenders, selling their commitments to cover the upfront costs of platform and building construction. Coach, the luxury-handbag maker, has been the first to commit, buying 15 stories of the 56-story southern tower. “We will make our money in residential and retail,” says Ross. “We don’t need to make our money in office space.”

Design is the other big selling point. The glass-covered, LEED-certified, high-tech new buildings planned for the Yards represent a minute supply of streamlined, more cost-efficient office space. New York City has exponentially more office space than any other city in the US. Yet in Manhattan, where most of that Class A office building stock lies, more than 65 percent of it is 50 years or older. And only a fraction of that remaining 35 percent has been built within the past 10 years since light-filled glass walls, energy-cutting technology and wide-open work spaces gained popularity.

Ross would control most other parts of the new neighborhood: In January he bought a partnership stake in Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group, which will oversee the development of all catering and restaurants at Hudson Yards. In 2005 Related gobbled up luxury gym chain Equinox, which will handle the workout spaces. He’s even vertically integrated construction materials, opening a plant in China six years ago to cheaply manufacture curtain wall and stone and the like, allowing the company to cut out middlemen, push construction costs down and increase quality control.

So will he actually get this done? Probably. The real estate market is rebounding, the project has the air of inevitability, and the city has offered tax breaks, in addition to the key infrastructure investments. He’s also brought in a Los Angeles-based general contractor, Tutor Perini, much to the chagrin of New York’s territorial unions and union contractors.

“We are in a new paradigm in this country, not the same fast-growing country as before, unfortunately,” shrugs Ross. “So we are looking at where all those costs are and how we can eliminate those costs.”

Even so, it’s still not an easy sell. Ross says that his team is negotiating with tenants who could assume up to 22 million square feet in aggregate, though that will take some master salesmanship. Hearing that the window of opportunity to snag a prospective tenant is closing, I watch as Ross tells Cross to visit the company’s president immediately—despite the fact that a meeting has not been formally arranged and that it is Cross’ birthday.

“Look, it’s a lot of fun,” says Ross. “Because it’s not all about the money, really, it’s about transforming something and what you leave behind. This is a legacy.” For Ross, and for New York City.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)