The Gold Rush

The RBI needn’t have helped an asset bubble by buying gold from IMF

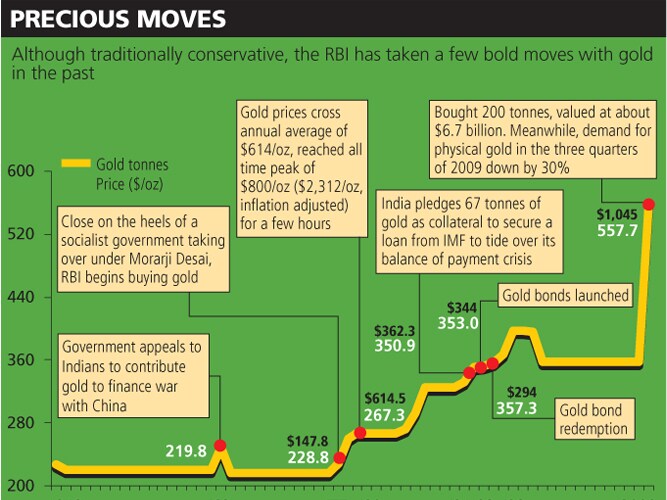

In the first week of November this year, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) surprised almost everyone in the world by announcing that it had purchased 200 tonnes of gold bullion, valued at about $6.7 billion, from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

According to an RBI statement, this was part of the RBI’s foreign exchange reserves management operations. But the rationale for this move has — as is typical of the RBI — not been explained further. Questions have been raised as to whether this opaqueness is acceptable in a democracy like India. Nevertheless, gold punters lost no time in marketing this move as a vote of confidence that India’s central bank had in this yellow metal. Not surprisingly, the price of gold has soared since then.

An Aberration

In September, the IMF decided to sell 403.3 metric tonnes of gold from the 3,217 tonnes it had in early 2009. Surprisingly, while cash-surplus countries like China and Russia haven’t purchased gold from them, only India and Sri Lanka — both debtor countries — have purchased gold. Global gold data sources put Sri Lanka’s purchase at 5.3 tonnes. But the country’s central bank assistant governor Nandalal Weerasinghe did not confirm estimates.

Whatever the actual figure, it left some market watchers amused. In the case of India it was even more surprising, because the RBI has consistently maintained a very conservative policy on gold. It even refused to allow Indian banks to purchase gold under the Gold Accreditation Plans where banks wanted to keep part of their own cash reserve ratio amounts in gold.

A Better Way?

What galls market men is that the RBI could have benefitted Indians. For starters, there is an outflow of cash upfront. The IMF deal makes the RBI pay for this gold at market-based prices.

So what could have been the alternative? If the RBI actually wanted the gold for its reserves, it could have floated a gold bond scheme, as in the early 1990s inviting Indians to offer their gold to the RBI in exchange for a promise of redemption volume for volume (irrespective of price) say 10 years later. Investors could also earn 1 or 2 percent interest on such deposits.

The gold bond scheme would not have caused any outgo of funds. At present, the RBI has blocked its funds in an asset that has no function except as a collateral for forex borrowings — available more easily from Indians themselves.

The RBI would have allowed India’s private gold to come out from the vaults into the open market thus becoming an economic asset that is now productive.

The Implications

Lastly, and most important, the RBI has become an interested party to protect the value of gold at over $1,000 an ounce. This means that RBI has contributed to an asset bubble by buying gold over $1,000.

A similar situation had taken place in 1980, when market men advised people to purchase gold when it crossed $400, and then $600 and then touched $800. Those who purchased the gold even at $500-600 haven’t recovered their investments in inflation adjusted USD.

These high prices are peculiar in the face of falling demand. According to the World Gold Council demand for physical gold in the first three quarters of 2009 was down by 30 percent compared to 2008. There will be a price correction. “What people do not realise is that gold’s strength is its own enemy. None of the gold gets consumed. It is preserved. Even gold dust is collected and recycled. Hence, any incremental supply remains in the market forever,” explains Bhargav Vaidya, a commodity trader who specialises in gold.

The RBI’s purchase of gold couldn’t have come in at a worse time.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)