- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Intermediary Rules much worse than believed

Intermediary Rules much worse than believed

Legal experts, technologists and civil society activists believe while some elements of the rules work, many are ambiguous, cumbersome and strenuous on fundamental rights

Aditi covers technology, privacy, surveillance and cybersecurity. You can send tips at aditi.agrawal@nw18.com or at mail.aditi@pm.me. Email for Signal/WhatsApp details.

- West Bengal considering state legislation to act against apps like Sulli Deals: Derek O'Brien

- Parliamentary panel's version of Personal Data Protection Bill endangers privacy: Justice Srikrishna

- BJP MPs successfully thwart attempts to discuss Pegasus issue in IT Parliamentary Committee

- Overview: Facebook, Twitter, Google and Koo file first compliance report under new IT Rules

- PTI sues Centre, calls digital media code state's 'weapon' to control media

- Mobile internet services suspended in most of Haryana until January 30

- Traceability and end-to-end encryption cannot co-exist on digital messaging platforms: Experts

- 'Poorly planned, India not ready for 5G deployment'

- PTI sues Centre, calls digital media code state's 'weapon' to control media

- Facebook, WhatsApp sue Indian government over traceability requirement

You are reading this article on forbesindia.com. You are either connected to a Wi-Fi or to a cellular network, both of which are enabled by a telecom service provider (TSP), an intermediary. Or you might be in a cyber café, another intermediary. Maybe you decided to go anonymous and thus used a VPN. That’s an intermediary. Forbes India bought the domain from a domain registrar (such as GoDaddy) and might be using a content delivery network (CDN such as Cloudflare) to deliver videos to you quickly. The site might be hosted elsewhere (such as HostGator) while the magazine’s data may live on certain servers (such as Amazon Web Services or Google Cloud Provider). We might be editing our article on a content management system (such as WordPress). We might be processing your subscription payment via Razorpay or CCAvenue. All of them are intermediaries. You may have looked up this article on Google (intermediary), came across it on an RSS feed (intermediary) or saw it on Twitter (intermediary). You may even choose to comment on this article, thereby making at least that section of forbesindia.com, you guessed it, an intermediary. You may now decide to head to Amazon or Bahrisons to buy a book on intermediaries. Both of them are also intermediaries.

Related stories

Practically all Internet Service Providers (ISPs) are intermediaries.

Given their pervasiveness, any attempt to regulate them is bound to have a cascading effect on the entire internet and how we access it.

And that is precisely what happened when the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) notified the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 on February 25.

Apart from the Information Technology Act itself, and the still-awaited Personal Data Protection Bill and the National Cyber Security Strategy, no other legislation—delegated or otherwise—has the kind of impact on internet-based and related services as the Intermediary Rules. The reason is simple: Our access to the internet is enabled by a chain of interlinked intermediaries—intermediaries are basic internet infrastructure. If one goes down, major chunks of the internet get affected (read: Fastly outage, Google Cloud outage).

An intermediary only “receives, stores or transmits” electronic data on behalf of another person but does not produce it. As a result, the idea is that it cannot be held liable for the content that third parties disseminate using it and must have “safe harbour”, that is, immunity for intermediaries from liability for third-party content. The Indian Information Technology Act, 2000 recognises that and thus offers safe harbour under Section 79 while the American Communications Decency Act offers it under Section 230.

Safe harbour is considered essential for proliferation of internet-based services and to enable the polymorphism and malleability that are among the defining characteristics of the internet. Its abrogation, on the other hand, instils fears of private companies cracking down on free speech in order to evade liability.

This immunity from liability is not unconditional. The intermediaries must fulfil certain basic due diligence requirements to qualify for this immunity. And that is precisely what the Intermediary Rules sought to do.

At the heart of the matter is a deceptively simple question: Until what extent are platforms exempted from liability and when do their obligations to take down problematic content start? Through such interventions, are intermediaries automatically becoming arbiters of content? Does merely labelling content as misleading wreck a platform’s safe harbour or is it a good faith measure necessitated by the need of the hour, if not law?

With these hefty considerations, it must be said that it was unlikely that any Intermediary Rules that the MeitY notified would have garnered criticism. However, as Forbes India’s conversations with legal experts, civil society activists and technologists reveal, while some elements of the rules work, they were not expected to be this ambiguous, cumbersome, and strenuous on fundamental rights. The Rules have drawn criticism from across the world.

On Wednesday night, Nick Clegg, former deputy prime minister of the UK and the current vice president of global affairs and communications at Facebook, called these rules “highly intrusive” which is why Facebook (along with WhatsApp) is challenging the traceability requirement in court. He was speaking at Rights Con, a digital rights conference organised by Access Now.

Social media intermediary is too broadly defined

Forbes India spoke to more than 20 legal experts, policy professionals, activists and technologists to understand these rules and there was a consensus amongst all of them that the definitions of social media intermediary is too broad.

Common sense understanding (and the repeated stand-offs between Twitter and the Indian government, summons to Facebook over content moderation, cases against WhatsApp to enable traceability before the notification) suggests that only social media platforms, as understood in common parlance, should have been included here. While platforms such as Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, Koo, JioChat and Sharechat were meant to be covered, the definition is broad enough to include email (Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo! Mail), collaborative tools (Google Docs, Office 365), comments sections of all kinds (on Zomato, Amazon, news websites, even on Namo app) and cloud storage providers (Dropbox, Box, Google Drive) as social media intermediaries. Even multiplayer online games that have chat features, such as Ludo King or World of Warcraft, are social media intermediaries. And whenever they have more than 50 lakh registered users in India, they are significant social media intermediaries (SSMI).

And because there is no exemption for government intermediaries, MyGov, a citizen engagement platform with more than 1.7 crore registered users that was developed by MeitY’s Digital India Corporation where users can discuss new government policies, is an SSMI.

“The definition is reasonably vague because it talks about enabling any sort of ‘online interaction’ between two or more users. While the intention is to clearly regulate social media, as it is understood in common parlance, the definition is wide enough to include cloud telephony services,” says Nikhil Narendran, partner at law firm Trilegal. “Even if you just open a chatbox to enable messaging, you could be an SMI. For instance, an app which enables messaging for a trading website, which, as a part of trading, lets users communicate with each other, even if it is limited to certain aspects of the trade per se, and it has 50 lakh users, it will have to comply with these things.”

An earlier iteration excluded business-oriented transactions, search engines, email services, etc. from the definition of SMIs, exemptions that were worth preserving, Narendran said. Such exemptions would have brought the Intermediary Rules in line with the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 as well.

In a right to be forgotten case dealing with Facebook and Instagram photos of a woman that were shared without her consent on a pornographic website, and have thus become “offensive by association”, a single-judge Delhi High Court bench directed Google to use automated proactive tools to take down content that is “exactly identical” to content that has already been taken down.

(Right to be forgotten is not a statutorily recognised right in India yet, but in the landmark 2017 Right to Privacy judgement, the importance of the right, was recognised. As per the judgement, the right to be forgotten is not an absolute right that allows for erasure of criminal past, but “there are variant degrees of mistakes, small and big, and it cannot be said that a person should be profiled to the nth extent for all and sundry to know”. In the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, right to be forgotten is recognised as one of the four rights a user has.)

This obligation, exists only for an SSMI and Google, by its own admission and subsequent appeal against this decision, said that it is not an SMI but a search engine that only indexes search results. However, interestingly, even in Google Search, it is possible to comment on things and review them, thereby arguably making the ‘search’ function itself an SMI. For instance, if you search for the movie Inception, the search engine solicits ratings and reviews from the audience.

Here's a fun fact: While intermediaries have obligations and SSMI (SMI with more than 50 lakh registered users) have additional obligations, social media intermediaries by themselves don’t. As a result, defining who a ‘registered user’ is of elevated significance, but the rules do not do that.

“How are they counting registered users? Are they depending on DAUs [daily active users] or MAUs [monthly active users]?” asks Torsha Sarkar, policy officer at the Centre for Internet and Society. Or are they going by total registered users? What happens to dormant accounts or when the user count goes down? “Honestly, it is quite hard to lose registered users… People rarely actively go and delete their accounts,” says Udbhav Tiwari, public policy advisor at Mozilla. And is there a difference between paying and free users? “According to me, both—free and paying—users will be registered as long as they give their details. I don’t think the rules take into account dormant accounts,” says Priyadarshi Banerjee, a Supreme Court lawyer who has represented both Twitter and Google in the past.

The problem of artificially inflated user counts is a real one. For instance, if a user has a personal email account, another email address provided by their workplace, and another by their alma mater, do they count as one user or three registered users? “Ideally, they would be counted as three users. However, if they were to start verifying the actual identity of each and every person, then one could possibly argue out but the question is whether they want to do that exercise,” says Narendran.

The truly terrifying: News publishers must provide details of user accounts with all intermediaries

In December 2020, Hindustan Times reported that a group of ministers (GoM) was working on overhauling the government’s media and public outreach and the report generated by the GoM sought to “constantly track ‘negative influencers’, and to engage with ‘positive influencers’ to put the ‘government’s view point in the right perspective’”. The GoM proposed to actively identify journalists who had recently lost their jobs and are “supportive of the government or are neutral” so that their services “could be utilised” by different ministries.

Few days after the rules were notified, in March 2021, The Caravan reported extensively on this GoM report. In this report, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, Union minister of minority affairs, had observed, “We should have a strategy to neutralise the people who are writing against the government without facts and set false narratives/spread fake news.” The report assigned the responsibility of “constant tracking of 50 negative influencers” to the Eletronic Media Monitoring Centre of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MIB). Forbes India has seen a copy of this report.

Separately, in April 2018, the MIB had released a bid to establish a Social Media Communication Hub through which it would analyse large volumes of data across multiple social media platforms in real-time and even monitor individual social media users and accounts apart from identifying influencers. This was challenged in the Supreme Court by Trinamool Congress MP Mahua Moitra and subsequently withdrawn by the government.

However, Rule 5 of the Intermediary Rules essentially outsources these two projects and places the onus on the news publishers by way of intermediaries. As per Rule 5, all intermediaries are supposed to inform news publishers that in addition to the common terms of service for all users, the publishers must also furnish details of their user accounts to the MIB. On first reading, one would assume it is only for social media accounts. But it is for all intermediaries. Thus, Forbes India, Newslaundry, Scroll, The Wire and The Indian Express, among others, have to turn over not just names of their Twitter handles and Facebook pages, but also details of their TSP, cloud service provider, email service provider, payment service provider—the entire litany of intermediaries listed in the lede to the MIB.

“You need to reveal your outreach to the customer in which there is any official communication happening to the public on behalf of your publication,” says Narendran. However, one would need to keep in mind that if business services such as cloud service providers are expected to ensure this compliance, the government could use it to direct such cloud service providers to de-platform digital news services that are critical of the government.

Calling this rule “very excessive”, Narendran said, “This is a free speech problem more than anything else.” For Sneha Jain, partner at Saikrishna &Associates, it is clear that the government wants to control all form of dissemination.

“There’s no justifiable reason for the government to get details of such accounts. What is the government trying to do? It is a symptom of the government trying to exert excessive control over free speech itself. It’s one thing to instruct a publisher or intermediary to takedown illegal content. It’s an entirely different point to constantly monitor what’s happening on the platform, which to my mind is extremely intrusive and it could be struck down in a court of law,” explains Narendran.

This also poses a massive cybersecurity risk as it will create a single database within the MIB that will lay bare the entire technical infrastructure of news publishers.

Furthermore, there is nothing in Rule 18—which informs publishers to furnish information to MIB—that puts any restraints on what kind of information the MIB can solicit. “The aim of the rule seems to be to go after the pipelines via which publishers disseminate news content. While the information asked for is limited by Rule 18 and the form would suggest some curtails, Rule 18(4) is a big concern with potential for scope creep,” Jain said.

Need to hire officers located in India stems from a law enforcement demand/need

The lack of local officers for social media platforms in India has been a sore point for law enforcement agencies across the country. In the absence of such officers, the police have to rely on the MLAT (mutual legal assistance treaty) process which is a long and strenuous one. Anyesh Roy, deputy commissioner of police who heads Delhi Police's Cyber Crime Cell unit, had in 2020 told this reporter that the MLAT process often “strangulates” the investigation as it takes 12 to 18 months for it to yield results, if any.

Roy tells Forbes India that some of these rules, such as appointment of local officers, has been a longstanding demand of law enforcement agencies. “We always face trouble when we have to interact with an email ID. With just an email ID, we do not know who is behind it, whom we should escalate to in case we don’t get a response, especially in urgent situations such as where a woman is being harassed online. We are not able to escalate our concerns,” he says.

Brijesh Singh, inspector general of Maharashtra Police (Cyber), also voiced similar problems. “Despite having law enforcement request portals, there is no standard procedure as to when they will reply, how they will reply, what kind of information they will give,” he says. Such information is often “absolutely essential” to investigate crimes, collect evidence, nab perpetrators and get leads.

Banerjee, who has dealt with such requests in the past, tells Forbes India that having resident officers bypasses the MLAT problem. “When they would request information, a Section 91 CrPC [Criminal Procedure Code] notice [for information] was not always sufficient. While intermediaries in their discretion (as they determined urgent and expedient) had often acceded to information requests by LEAs, no law could compel a foreign intermediary to do so, unless the MLAT procedure was followed. LEAs had to route the notice through MLAT to get an appropriate response, in case a foreign intermediary refused to divulge any specific information. However, now if your point of contact is situated in India, and the officer on whom the obligation of compliance entirely rests is a resident in India, there is no question of resorting to or requiring MLAT,” he says.

Banerjee explains that the MLAT process incorporated a sense of filtering what sort of requests can be made and what will be ultimately validated at the end of receipt, which no longer is the case. “Today, if they receive any information, they may simply give it. The chance of an MLAT refusal—because MLATs were more often than not refused at the embassy stage on grounds that they did not satisfy the requirements for issuing such summons or an order—would not be the case.” Banerjee mentions a 2011 case in the Patiala House Court, Vinay Rai vs Facebook and Ors, in which a whole host of foreign social media companies, including Orkut, were summoned. MLAT was invoked to serve notices to the foreign intermediaries but it was refused at the embassy stage because of which all the foreign intermediaries were dropped. “That will no longer be the circumstance as all enforcement will be through a Nodal Contact Person so there will be no filtering through the MLAT process,” he said.

Banerjee says the 72-hour deadline, without the resident nodal contact person, would begin once the MLAT process is satisfied. And the MLAT satisfaction process, that is, getting passing the muster at the embassy stage takes three to six months, if not longer.

Without the local officer, the process was quite onerous. Once a Section 91 CrPC request is raised by the police, it is routed to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). MHA then sends it to the embassy (American Embassy in most cases). The embassy then decides whether to reject it or to push it ahead to the US. If it is sent to the US, it is serviced only after it is endorsed. It is almost like the information request undergoes immigration. “This is because all our laws are territorial because of which any extra-jurisdictional requests, orders are empowered only if bilateral or multilateral treaties exist honouring those,” says Banerjee.

“In the previous scenario, if the request was routed through MLAT and it passed the MLAT muster, in an ideal world, the foreign intermediary had no choice but to turn over the information. Now, the MLAT filtering will not be there and the information request has to be complied within a given period of time. In that sense, there is no additional discretion [of the intermediary] that is being taken away. The previous system included bureaucratic filtering that has now been removed. The liability still remains the same.”

The rules now require SSMIs to hire or appoint three officers in India—Chief Compliance Officer (CCO), Nodal Contact Person (NCP) and Resident Grievance Officer (RGO). All of them have to be resident in India and must be senior employees of the company. The CCO is personally liable for ensuring compliance with the Information Technology Act, including the due diligence requirements laid down in the rules. The NCP is the contact person for 24x7 coordination with law enforcement agencies and officers to ensure compliance with their orders or information requests. The RGO is responsible for dealing with grievances.

For Roy, this will improve communication with the intermediaries, especially because a local person is able to “appreciate the local concerns better, so the response is comparatively better”. Having local officers helps train law enforcement agencies as well. “After the larger social media platforms appointed an officer here—either a liaison officer or a grievance officer—things have really changed. Such platforms have given training to law enforcement (agencies/officers) on how to interact with them, in what format the information should be asked, what can be given what cannot be given, what are the authorised emails which are allowed to ask information from these intermediaries. A lot of this space has been sorted out once they put in an officer,” says Singh.

Banerjee explains why MLAT wouldn’t be required anymore: “Let’s assume the NCP is an American citizen who is now sitting in New Delhi. In that case, the Section 91 CrPC notice does not need to be routed through the embassy anymore. The police will simply go to the office and serve the notice to the NCP and say this is the notice for information request and we require this information, please follow the timelines that are now statutorily stipulated.”

Roy, on the other hand, clarifies that this does not mean that the need for MLAT (mutual legal assistance treaty) requests is completely effaced. “MLAT is required only when an activity pertains to an individual or an organisation which is not within India’s physical or legal jurisdiction. Presence of the nodal contact person will definitely help law enforcement agencies communicate our concerns even in such matters,” he says. He adds that in certain cases, even when both the victim and the suspect were in India, intermediaries asked for MLAT. “The presence of a local officer will help in communicating our concerns and prevent the recourse to MLAT,” he says. Singh, too, says in cases where evidence is in some other territorial jurisdiction, they would still rely on MLAT.

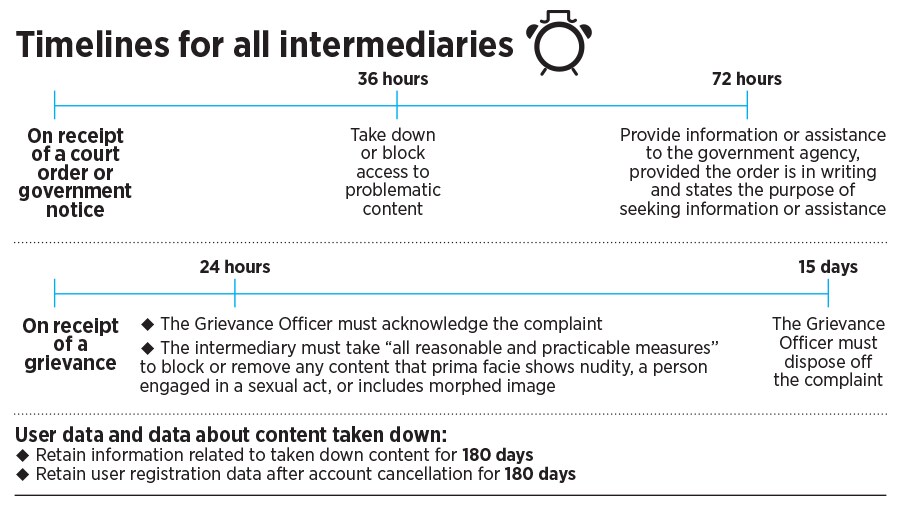

For Roy, complying with deadlines—72 hours for information requests, 36 hours for content takedowns, 24 hours for content showing nudity without consent—is a realistic and attainable goal for the intermediaries. “These timelines have been given after due consultation with these platforms and deliberating on the reasonableness of them because ultimately they have to enforce them,” he says. In most cases, the intermediaries comply with the content takedown deadlines, he adds.

Not only is the 72-hour deadline for turning over information to law enforcement agencies viable, it should be done instantly, Singh says. “The nature of information that is on the servers will not change, so why the delay?” he asks. And if users are using VPNs, it should not make a difference because it is not as if Facebook has to do the investigation, he adds. “It is just a copy of the information available on their servers which they should give me.”

However, placing personal liability on one of the officers paints a target on their backs. As a result, it has been hard for the larger, non-Indian platforms to hire in-house CCOs.