Enabling entrepreneurs to alleviate India's energy poverty

A change in the law could extend electricity to millions of people

An estimated 360 million to 460 million people in India have little or no access to electricity. That’s roughly a third of the people in one of the world’s most populous countries, and more than the United States and Canada’s populations combined. In terms of these raw numbers, India suffers from the most extreme energy poverty in the world.

As a basic lack of power is a major impediment to economic growth, the Indian government has articulated ambitious electrification goals to extend access to those people, many of whom live in rural areas currently beyond the reach of the central grid. These goals come at a time when the public utilities are under financial distress, however, so the hope is that private enterprise might help fill the gap. And yet, says Stanford GSB professor Stefan Reichelstein, “those electrification goals are not being met left or right.”

In a new research paper, Reichelstein and Stephen Comello, associate director of the Sustainable Energy Initiative, identify a key regulatory barrier that they believe is freezing the government’s hopes that entrepreneurs will step in to accelerate the effort to power upward of 80 million homes that lack electricity. The research was funded partially by the Stanford Institute for Innovation in Developing Economics.

Central-Grid Woes

One of the main complicating factors in India’s energy puzzle is the poor financial health of the state-run distribution companies, or discoms. These companies are required by law to deliver electricity to residential and agricultural users at highly subsidized rates that do not come close to covering their full cost. The resulting losses are exacerbated when discoms extend the central grid to unpowered villages. In other words, Comello says, “if you don’t have electricity, don’t look to the central grid to give it to you because they can’t afford to bring it.”

Given the mismatch between the government’s lofty goals and the public utilities’ inability to provide the infrastructure, Reichelstein says, the government is left with a natural question: “Could entrepreneurs or other entities fill this role at a more distributed form and smaller scale?”

The answer, as it stands, is mixed. While private capital has flowed to some very small-scale projects such as solar lanterns or solar home systems, it has been virtually absent from the types of systems with the greatest economic potential. After analyzing the economics at play and interviewing dozens of players in the field, the researchers believe they have identified the sticking point.

The Mini-Grid Solution

The researchers first calculated the costs of the various alternatives to central-grid electricity and identified which would be the most attractive for private developers. These options can vary both in generation source (the most common being kerosene, diesel, and renewables) and size, from micro-scale systems capable of charging small devices to pooled generators shared by individual homes to mini-grids capable of powering entire villages.

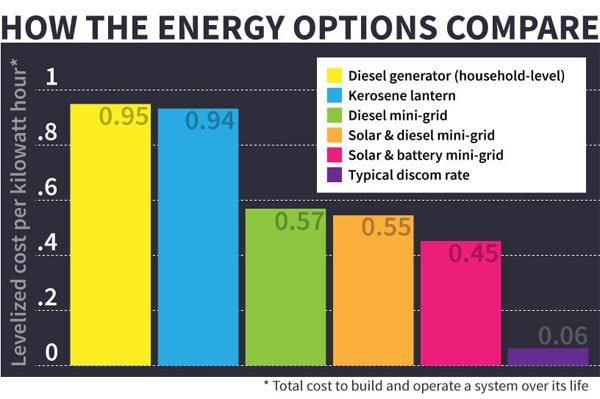

The researchers’ cost analysis suggests that solar-powered mini-grid systems with storage should be an attractive option for private investment. For one, the cost per kilowatt-hour of mini-grid electrification for consumers is cheaper than other common services like kerosene-based lighting and diesel power generation (see chart), and consumers’ willingness to pay for energy services would likely exceed the costs associated with building mini-grid systems. Mini-grids can also provide a foundation for economic development because, like the central grid, they can provide for productive capacity to power machinery or communications towers, for example. Mini-grids powered by solar photovoltaics and storage can also easily scale up as electricity demand rises, thereby providing a flexible and carbon emission-free source of generation.

India has abundant sunshine — on par with Arizona and California on average — and the government has made solar power a centerpiece of its energy goals. The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy recently set a target of installing 100 gigawatts of solar power capacity by 2022 through its National Solar Mission. “To put that into perspective,” Comello says, “right now they have approximately 5 gigawatts. So they need to grow at an incredible rate.”

The Holdup Problem

But the researchers noted that, despite the entrepreneurial catnip of this massive untapped market, private enterprises weren’t rushing to meet India’s energy demand. To get to the bottom of this, the researchers spoke to dozens of entrepreneurs, policymakers, and analysts in India.

What surfaced from these discussions was something outside the range of typical technological or financial challenges. “What kept coming up was the barrier that an entrepreneur can do nothing about — the threat of central-grid extension,” Comello says. In other words, even though the central grid is unlikely to reach unpowered rural areas as a general rule, the simple threat that it could puts private development at an impasse. Entrepreneurs can’t compete with discoms’ highly subsidized rates, and in fact there have been multiple instances where the central grid extended to a mini-grid and forced the operator out.

What’s more, Indian laws expressly written to spur these private developments have in fact made the problem more intractable, says Reichelstein. “In the case of a mini-grid, you don’t need a license from anybody to distribute electricity, whereas in most other countries in the world, you do. So if entrepreneurs want to go in and set up electricity off-grid, they’re free to do so.” But that is a double-edged sword, one government official told the researchers. Private developers have no legal standing as an entity entitled to distribute electricity, and thus no way to protect their assets should the central grid extend to a village they had tried to electrify with a mini-grid.

“You potentially have a huge gorilla walking into the room at any time that you can’t control,” Reichelstein says.

As a result, the prospects for deploying electricity with productive capacity to those experiencing energy poverty in India remain vastly unfulfilled.

The Sweet Spot of Regulation

The good news is that a fix isn’t all that difficult or costly, Reichelstein says: “Because it is really a set of regulations that needs to be written, you don’t have to deploy billions of dollars.”

India has seen some movement. Uttar Pradesh has passed the first formal state policy that explicitly considers mini-grids, a good first step but imperfect, the researchers say. And the Forum of Regulators, a key advisory body of state and central electricity regulators, has put forth a policy proposal that would begin to untangle this impasse and encourage private development.

In their research paper, Reichelstein and Comello endorse the proposal, while suggesting some modifications on how electricity rates would be calculated and collected, and the terms under which discoms would purchase private developers’ assets.

Putting these new regulations in place, Reichelstein says, should mitigate the risks of private development and offer a solution should the central grid come to a village that has been covered by a mini-grid. “Our proposal is, in case the grid comes to this area, the solar entrepreneur can say, ‘I can’t compete with your highly subsidized electricity rates, so I am selling you my mini-grid infrastructure assets at a rate that has been set in advance by the regulators.” That price would protect the entrepreneur’s investment, as if the grid extension hadn’t occurred.

“Given the renewed commitment that India has made not only to electrification, but also to sustainable energy, and given that solar is such an attractive resource, this is a very natural angle,” Reichelstein says. “It’s low-hanging fruit.”

This piece originally appeared in Stanford Business Insights from Stanford Graduate School of Business. To receive business ideas and insights from Stanford GSB click here: (To sign up: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/about/emails)