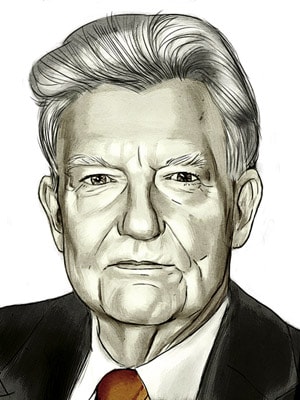

Paul Johnson: Power of the Irrational is Formidable

International ranking and prestige are not the abiding parameters of a great nation

What are we to do about Europe? Can the euro survive? Is the EU doomed? Far from promoting Continental prosperity, does this institution now constitute the principal reason the world is still bogged down in the longest recession in half a century?

Everyone asks these questions, but no one provides any answers. In Brussels the thousands of well-paid bureaucrats, who thus far have escaped any cuts or austerities, keep their heads down and quietly get on with the job of enforcing countless minute regulations.

Recently a senior European figure warned the British that unless they became more deeply involved in the EU, Britain would sink to the level of significance of Norway or Switzerland.

If this was intended as some kind of rhetorical threat, it was ill-judged. These countries are prosperous, law-abiding, peaceful and well-governed. Their standards of living are higher than Britain’s, their homicide rates are lower and in most statistical criteria they score high. It’s true that neither country is a permanent member of the UN Security Council, as Britain still is. Nor are they automatically invited to most meetings where the future of the world is discussed. Britain still sits at the top table for most purposes, though in increasing discomfort. It certainly isn’t a superpower—although it can be argued that Britain is still a great power. But what good does that do its people?

I wish questions about international ranking and prestige were asked more often. No other subject produces such irrational judgment. For instance, Iran has been striving to become a nuclear power for a decade, though its government denies any such intention. Presumably Iran’s driving motivation is to increase its power in the region. But the penalties, in the form of sanctions, for its people have been high.

Iran has the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves and second-largest natural gas reserves. Had it devoted itself to developing its oil and natural gas potential, Iran’s clout in the region—and beyond—would be much greater than any notional power gained from creating a nuclear bomb.

Look at neighbouring Pakistan. It has been a nuclear power for some time, but this has imposed a huge burden on its defense budget, not least in keeping the nuclear arsenal secure from terrorists. It’s unclear whether possessing nuclear weapons adds appreciably to Pakistan’s security or if it merely adds a new dimension of problems to governing this unruly and unstable country.

Two advanced industrial nations that have flatly refused to enter the nuclear club are Germany and Japan, yet it’s hard to see how they’ve suffered from the decision. Both are doing pretty well in their respective regions. Japan could point to the curious case of its neighbours, North and South Korea. The North possesses nuclear weapons yet has one of the world’s lowest standards of living. The South has no nuclear ambitions yet basks in remarkably high—and rising—prosperity.

Which brings us back to Norway and Switzerland. Neither has nuclear weapons, yet both, all things considered, have populations who seem happy to remain comparatively insignificant, provided they can also stay at arm’s length from the bureaucrats in Brussels.

Nevertheless, the world for the most part is not run by reason. The power of the irrational is formidable. I had to admit this while taking great delight in a recent photograph of François Hollande shot during a visit to London, when he was inspecting a Coldstream regiment guard of honor. Hollande was accompanied by a gigantic major, with drawn sword, who towered a distance of 2 feet or more above him. This infuriated the French, who accused the British of arranging the contrast deliberately.

Not so, I’m sure. But we Brits do not envy the French their diminutive president. And we’re glad we still have some redcoats to do a bit of towering.

Paul Johnson is an eminent British historian and author

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)