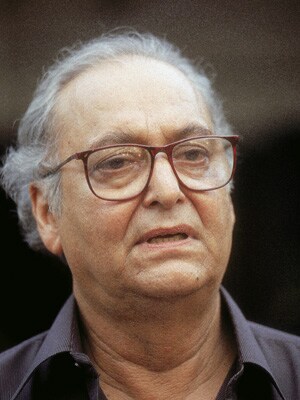

Soumitra Chattopadhyay: Applause At Last

The Dadasaheb Phalke award for Soumitra Chattopadhyay comes late in his life. Is it because his formidable talent is best regarded in retrospect?

The conferring of the Dadasaheb Phalke Award to thespian Soumitra Chattopadhyay, 77, this year is an instance of justice delayed. Ever since we first saw him playing the flute in a rented room in the suburbs of Calcutta in Apur Sansar (1959), we have been convinced about the cultural signification of the actor in a society trying to find an image of youth, dreamy optimism and humaneness.

Part of the reason for the delay is perhaps Soumitra’s loyalty to his vocation as an actor, rather than a star. Though one of the most popular artistes in Bengal, he still isn’t an “actor-with-a-biography”, as French philosopher Edgar Morin describes the phenomenon of stardom. Soumitra Chattopadhyay likes to make himself available in the public domain—in social protests, as an editor of a niche literary journal, a poet, a playwright, director and actor on the Bengali stage, an elocutionist, a brilliant conversationalist, a patron of city coffee-houses etc. After 40-odd years in front of the camera, he remains transparent, rejecting the distance that is mandatory for a box-office icon’s mythologisation.

This negation is all the more striking because, in world cinema, Soumitra occupies the same space as Toshiro Mifune, as commanding a presence in the oeuvre of Satyajit Ray as the Japanese actor was in Akira Kurosawa’s work. Described by critic Pauline Kael as Ray’s “one-man stock company”, Soumitra worked in 12 films with the auteur, showcasing his variations of expressions of a modern Bengali self, from a lyrical Apurba in Apur Sansar to a rough automobile driver in Abhijaan (1962) to a rustic Brahmin in Ashani Sanket (1973). For children, he is unmistakably Feluda, Ray’s fictional sleuth in a couple of films.

What is important to note, however, is that Soumitra was no Ray exclusivist. Iris Murdoch once described Jean-Paul Sartre as “self-consciously contemporary”. The term can be applied to Soumitra as well who, despite his conventional good looks, refused to stick to idealised romantic roles. Consider Mrinal Sen’s Akash Kusum (1965), where he dared to play a flawed romantic hero: A young man showing off, pretending and lying to win his lady love; the affair fails but the protagonist wins audience sympathy for portraying the uncertainty and mediocrity of post-independence Bengali masculinity.

In the turbulent late-1960s, Soumitra rose to prominence with a romantic image different from that established by Uttam Kumar in popular cinema. In Tin Bhubaner Paare (1969) or Pratham Kadam Phool (1970), he played heroes who did not quite fit in, who carried a social lack within themselves. In Baghini (1968), interestingly, he appeared as a Marx-reading Leftist amongst village women who procure illicit liquor for subsistence.

These deviations from the idealised were evident even in Ray films like Kapurush (1965). To my mind, this exploration of cowardice—personalised in Soumitra’s role as Amitabha Roy—had a metaphorical undertone awaiting a more minute examination in Aranyer Dinratri (1969). Urban men, driven by sexual conquest, bear testimony to the modernist confrontation with their political passivity.

Historically speaking, Soumitra represented the cultural space that articulated all the unfulfilled promises of 19th century modernity. No longer was it possible to recreate the ambitious project of Young Bengal or Bengal Renaissance; already there were signs of defiance and discontent in the social scene. Mainstream cinema, therefore, demanded a different model of youth: It found him in Soumitra, twisting to a popular number after winning a local sports event in Tin Bhubaner Paare.

Soumitra’s career path and his challenges of choice ran parallel with that of the legendary Uttam Kumar. While Uttam had the image of a friendly neighbour, Soumitra represented a more sophisticated urban middle-class sensibility. Nowhere was it more apparent than in Ajoy Kar’s Saat Paake Bandha (1963), where Soumitra was cast opposite screen goddess Suchitra Sen, with whom Uttam Kumar made a fabulously popular pair. Defying the secure enclave of the traditional romantic couple in Bengali melodrama, Soumitra blazed his own trail as an academic facing up to the fragility of a conjugal relationship.

Soumitra shared screenspace with Uttam Kumar in at least three major films: Tapan Sinha’s Jhinder Bandi (1961), Aparichito (1969) and Stree (1972) and also played Debdas to Uttam Kumar’s Chunilal in a 1979 version of the novel. Going by performances, in each of these films Soumitra represented a refined, latter day version of youth compared to Uttam’s decadent feudal lord.

Particularly interesting is Soumitra’s use of his face, which reminds us of Roland Barthes’s reference to Greta Garbo’s face as an ‘idea’. Soumitra, too, is an ‘idea’ in the modern Bengali psyche: Low-key, modest, refined, with neatly designed pronunciations, which distinguished him from other contemporaries like Anil Chattopadhyay, Biswajit or Basanta Choudhury. Soumitra also made his mark in character-roles like in Tarun Majumdar’s Saansar Seemante (1975) and often went against the grain to perform in villainous roles like in Jhinder Bandi, Pranay Pasha (1978), Pratisodh (1981) etc. In his mature years, he excelled in Raja Mitra’s biopic Ekti Jiban (1988), Tapan Sinha’s Atanka (1986), Saroj Dey’s Koni (1984), among others. Despite his remarkable range, however, Soumitra stayed away from Hindi cinema, because he was unsure of his verbal command over the language.

But any overview of Soumitra’s career would be incomplete if we did not mention his performances on stage, notably Tiktiki, a version of Anthony Shaffer’s Sleuth, and his performance as Lear in Suman Mukhopadhyay’s recent adaptation. A tribute to his mentor, Sisir Kumar Bhaduri, and also—in my opinion—a homage to the great Russian actor Juri Jarvet, Soumitra’s performance in King Lear deserves an independent chapter in the history of modern Indian drama.

Soumitra Chattopadhyay is more than an actor: He is a cultural presence and an institution by himself.

Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay is a professor of Film Studies at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and also an author and translator

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)