Remembering Prabuddha

An ode to late fashion photographer Prabuddha Dasgupta from his contemporaries who remember his timeless images

By Pablo Bartholomew New Delhi, September 06, 2012

Since your passing on so much has been said and more will follow in time, I guess. And I have been part of some of your life… knowing you all these years will remain important, being by you at the funeral by the sea was somewhat consolation. I helped with the cyberspace interventions that followed, posts by many people that you grew up or worked with, little anecdotes and stories emerged, I learnt facets about you, and on the 13th day after was your remembrance at the NGMA, the compound, where you played as a child. This touching memorial where your friends and family spoke lovingly and openly of you, leaving them very vulnerable and us all shaken… what else could we all do for you, a friend, a colleague, my brother-in-arms?

It is nearly a month since 12th August. A date that, as years go by, may become more important for me than the 15th. Like it is with the date 11th January, when my father left life. He died young at 58, but at 55 you even eclipsed that. You left too early and as you knew, it has taken me over a quarter-century to consolidate his life’s work, to be able to structure it as a series of gallery shows, a book of his photographs and finally now this thick book of writings about the birth of modern Indian art, of which your father is part of, but sadly you are not here; it would have been great for you to look, hold and have a copy.

Yes, you and me, we supported each other, needed each other to be able to make sense and reference the outside world, the larger happenings, the changes and the rumblings in the photography and art worlds. Our worlds intertwined, sometimes not because of choice but coincidences or circumstances that went beyond our generation.

Our parents’ worlds overlapped. The arts were the bridge that joined us in our youth. As a young nation was born, the idealism of nation building took over our parents. Both came from somewhere else to make Delhi their home. You had an artist father; mine too was an arts writer, a critic. Your father became an administrator of an art institution; mine did too, unfortunately mine died while holding his post. In our teens you moved into the house that we were leaving. You found my guitar left behind, you reminded me.

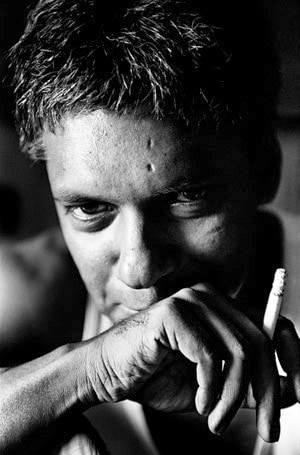

Image: Prabuddha Dasgupta

And in the many gangs in Delhi that I navigated growing up, the Nizamuddin gang was one that I was inducted into in my early teens. Between the many parks and riverbank hangouts that we had, this particular second floor barsati was where our young gang jammed on our guitars, bashed the drums, smoked up and hung out. And in the shadow of this house was this shy young girl who never joined us but of whom we occasionally caught a glimpse of, as we came and left that space. How was I to know then that years after, you would marry her? Yes, this very striking, large-eyed, petite, dark curly-haired girl with an artistic streak inherited from her father who ran a successful print and design studio in the city centre would become the mother of your two daughters. Decades later, with much nudging from you, I jumped back into the gallery world; it was at the tail end of the art boom years, this young girl I knew had grown up, and, like with your books, she designed mine for the gallery show in New York. And I must add, it has remained something of a cult collectable to date.

Beyond Delhi and the socialist intellectual world of growing up, our lives kind of tangoed in advertising. I, then a reluctant advertising photographer post my stint as a stills photographer, made some money from this industry, never wanting to commit totally to it, just looking at it as job work, exited within a decade of entering it; you stayed and navigated through it much better, keeping your grace, style and signature and I marvelled at your ability to keep your balance and composure. But all was not smooth sailing: Remember those nervous moments? While you pushed the boundaries in advertising, showing near nudity had its repercussions. Police complaints, the court, the arrest warrant, they were all daunting to deal with. I on my part as a comrade, offered to hold and hide your negatives, the evidence. Thank god it never came to that, the advertising agency handled it and the case dragged on…and was finally settled, I guess.

When you entered the art world, I was too busy working the international media scene. You pushed and pushed me towards your gallery. I, a reluctant rebel, had reservations about re-entering a world that took my father away and had kind of skirted around it for many years. Looking at your experience I did feel encouraged enough to go back into my archive and pull work out, something left abandoned for a quarter of a century.

You were a person that had your way, you were able to straddle the two worlds, in your personal work, playing with the intimacy of your thoughts through your books and exhibitions and yet for the outside world that most people knew you by, the calendars, campaigns, fashion and lifestyle magazine photography. Yet somewhere again both these intertwined, you were able to bring one to the other and vice versa.

And even in your personal life you were able to coexist with a healthy duality, breathe and be a father and yet live away with another, have an ease with both and make both have an ease with each other. That was your way, soft spoken, a quiet man, that one could not help but marvel at your resilience, the ease of both worlds, whether in work or in life.

But I say this as an outsider, an admirer, and however much I would like to claim that I knew you, I really didn’t. There was a closed side to you. Something densely private and I think we got on all these years as I met you on your own terms. If and when in Delhi, which was quite often, should you make that phone call then we would meet. And if you didn’t, it didn’t matter. After all you had homework to deal with; two growing daughters can be a handful. I enjoyed, however, your diktat: When in Goa, it was mandatory to stay with you. I did, the occasional times I did visit your part of the country. Not enough, I can say now with regret.

Now that you are no more, this loss remains. The loss of a friend, an ally, a partner in crime. That beacon is no more; the lighthouse light has gone out, bringing to the forefront all the more important nagging questions and issues. This writing on the wall concerns not just you and me but should be a worry to many others, photographers who are alive or the nearest ones to those who have passed on. What happens to the work after?

I dare say that in its 65 years, this very young nation of our parents’ generation has grown older but not wiser. What they may have set out to do has not been realised. The state art and archives, as institutions, flounder with politics and mismanagement; there are very few universities with departments of arts and aesthetics, and even those that are there are ill equipped, or have not been able to develop archives and museums to acquire and manage art. What they teach the students is just theory. In the private realm there are a few archives and foundations, but none of these have been able to develop the ability or capacity to handle and preserve photography or a photographer’s entire estate. So, if in the living of life we thought things were complex enough, in death, my dear friend Prabuddha, it becomes even more complicated.

Pablo Bartholomew is an internationally-awarded photographer who has worked editorially with magazines and newspapers for the last 30 years. His work will show at Shanghai Art Biennale this October, work that was created in his early twenties in Bombay.

By Colston Julian Mumbai, August 18, 2012

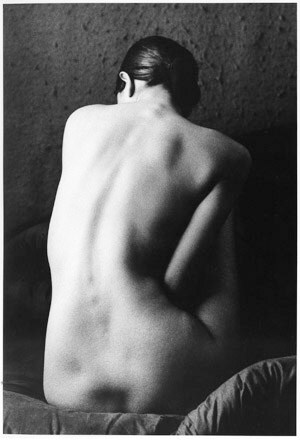

I remember first seeing your work when I was just out of college. The striking, yet poetic black-and-white images, and the women in them, were beautiful yet strong (they were not always models, sometimes they were friends with interesting faces). At a time when glamour photography was cheekily getting away as fashion photography you always gave your images a subtle edge no one else could. You were a man, indeed, ahead of your times, and your images were timeless. When I look at the same images today, they are still relevant.

Image: Prabuddha Dasgupta

I first met you in Bangalore around 2001, through a common friend. As a young photographer in awe of your work, I was very keen to meet you. I had no formal education in photography, and had trained with a cinematographer. I learnt that you, too, did not undergo any formal education in photography. I looked up to you. We spoke for a while about various things. You were warm, and listened intently to me. I remember leaving your house, feeling like I had met an old friend. I knew you would have an impact on my life, and the decisions and choices I would make.

Over the years that I knew you, and was fortunate to accompany you while you were photographing your subjects, I learnt much from you, more about life than photography. I choose not to use the word ‘assistant’ or ‘assist’, as I genuinely don’t think you needed much assistance on a shoot. It was always the basics: The subject, the light (mostly daylight), and a conversation that translated into magical images.

One time, you called, asking me to lend you “a camera, lens and a light” as you had forgotten yours in Bangalore. Not knowing what you were photographing, I carried all my equipment (around a truckload), unsure of what you might need. When you saw the crew and equipment, you playfully asked if we were preparing for a film rather than a photograph. Eventually you used “a camera, lens and a light”, as you had said.

You, I soon realised, saw life differently, in its simplest form. You dressed simply: I never saw you indulge in designer clothes, even though you always had easy access to them. You were always yourself, had no ego, and never judged anyone. You had a charm no one could resist.

I feel you were always about change, be it your decisions about shifting from Delhi to Bangalore, and then to Goa, or being one of the earlier photographers to change from film to digital in India. You never shied away from trying to do something differently. You did not believe in awards—despite winning every single award in the country—and kept away from ceremonies. You always asked, “Why should we be judged?”

You were a passionate human being, and were about love. You worked with people you liked and loved, and have been a source of inspiration and integrity. You have not only inspired us with your work, but have given us visual poetry like no one else. You shall be missed, but your work shall always continue to inspire us.

Prabuddha Dasgupta—friend, mentor, guide, father figure—thank you, my dear Prabuddha, for letting us all be a part of your journey.

Colston Julian’s first serious photography job was a feature for Elle, which led to a long association with fashion photography.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)