From imagination to images

The adaptation of books into films has always been equally frustrating and rewarding

J K Rowling ensured the Harry Potter films remained faithful to her books

J K Rowling ensured the Harry Potter films remained faithful to her booksScience fiction writer Arthur C Clarke first sat down to watch the completed version of 2001: A Space Odyssey—for which he had co-written the screenplay, based on his short story The Sentinel—at a private premier of the 1968 film directed and produced by Stanley Kubrick. At intermission, he left the screening, in tears. For, despite having worked closely with Kubrick in the making of the film, the final cut was nothing like what he had thought it would be.

The incident was recalled and narrated by author Michael Moorcock, a friend of Clarke’s, in his introduction to the illustrated version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, published by Folio Society in 2016, and is a stark example of what can go wrong while reimagining a story in the process of translating it from one medium to another. Kubrick’s dream had clearly turned out to be Clarke’s nightmare.

Adapting books into films is, ultimately, a matter of imagination.

“Writing a book requires the imagination of the reader, while making a film requires the imagination of the filmmaker,” says film director and producer Kiran Rao. “They are two very different mediums—books and films—and have very different demands.”

Image: Movie Poster Image Art/ Getty Images

Agreeing with this difference is film critic Anupama Chopra: “Films and books are two very different art forms, and have very distinct ways of connecting with their readers and viewers. They both have very distinct beauties of their own. Books are about what the author puts on the page, and what the reader imagines it to be, while films are about what the filmmaker imagines it to be and puts on screen.” And caught between reading the book, and watching the film is the viewer whose imagination may not quite match that of the filmmaker’s. For instance, critics panned Ketan Mehta directorial Toba Tek Singh, which was released this August and was based on Saadat Hasan Manto’s short story of the same name, for failing to capture India’s and Pakistan’s madness.

But there are films, and filmmakers, which have managed to do exactly that—match the imagination of the viewer. “I am a huge Harry Potter fan,” admits Chopra, recalling how, when she was seven months pregnant with her second child, she had coaxed someone to stand in an overnight queue outside a London bookshop to buy the latest release from JK Rowling’s fantasy series. “But when I watched the films, I fell in love with them all over again. Everything was exactly the way I had imagined it; Hermione was exactly how I had thought she would be. It was just perfect. Watching the Harry Potter films was a very fulfilling experience.”

Every new film adaptation of a book raises the inevitable questions, such as how true the screen version is to the source material, and if it is better or worse than the book. While the first is a valid question—there are, after all, many ways to interpret the written text and present it in cinematic form—the second is perhaps an invalid comparison. Because what has been described over several pages, would often need to be condensed, and contained, in a single shot; and while an author has the luxury of space, a filmmaker does not quite have the luxury of time.

It did help that Rowling, although she did not write the screenplay for the films, maintained substantial influence over the filmmaking process to ensure that the films remained faithful to her books. Adapting the books, adored by millions, required maintaining a balance between remaining faithful to the book, and abiding by conventions and lengths of Hollywood blockbusters. Even then, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, a 700-page tome with fast-paced plot developments, needed to be sliced into two parts for its cinematic version.

Another similar tome, although several decades older, is Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 Pulitzer-winning novel Gone with the Wind. In the book, close to two pages are devoted to the description of the train depot where hundreds of injured soldiers from the civil war are laid out on the ground for medical treatment (or what little is available); Scarlett, the protagonist, has rushed there to find the doctor, because her cousin Melanie is having a baby back at home. In the film adaptation of the book, a single, 55-second shot pulls out from Scarlett’s sweaty, hassled, and increasingly shocked face to a bird’s eye view of the depot, where soldiers lie like felled logs, and the din of their pained groans is only drowned by the Confederate army’s trumpet call. Fifty-five seconds is a long time in a film, but Gone with the Wind was also infamously 3 hours and 37 minutes long.

“An author who is actually writing the screenplay for a film based on her own book will have to kill her darling,” says Rao. “There is always so much in a book that you simply cannot fit into a two-hour film.”

Soonie Taraporevala, who wrote the screenplay for the screen adaptations of Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey, and Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake, says that when you are working on the adaptation of a great book, you don’t have to invent much. “It’s more a question of what to leave out,” she says. “Novels are dense, long, and packed with character, plot, and incidents covering huge time spans. How to take all that and convert it into a 110 -page screenplay has always been the greatest challenge for me.”

More recently Kashyap adapted Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games

This can be especially tough when working with books that are popular and well-loved. “Such a Long Journey and The Namesake were both very well-known books. This created an added pressure, as well as joy in the process of adapting them into films,” Taraporevala adds. “Readers of those books don’t want anything to change in the process of adaption, but some things inevitably have to change when you are translating from one medium to another.”

Filmmaker Anurag Kashyap, who has adapted books such as S Hussain Zaidi’s Black Friday, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas and, most recently, Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games for the screen, says that his process of adaptation involves reading the material several times over, and breaking it down into chapters that can then be filmed. “For Black Friday, our approach had to be different, because the story did not have a clear protagonist. So the investigation itself [into the 1993 bombings in Mumbai] had to become the hero of the film.”

Rao thinks some books translate more easily into films than others. “The quality of the adapted work depends on the people who are bridging the divide between the two mediums, and if they have an innate understanding of what the writer is trying to say,” she says. “Every writer wants to see the spirit of the book staying on in the film.”

But unlike Rowling, not all authors wish to be part of the adaptation process. “Most good writers are already on to their next books and realise that a film is a different beast altogether,” says Taraporevala. “Mira [Nair, director of The Namesake] was in touch with her [Jhumpa Lahiri], but the first time I ever met her was in Kolkata at the film premiere. She was very pleased with the adaptation. Likewise, Rohinton Mistry stayed away from the adaptation process.”

A similar reaction came from Canadian author Margaret Atwood, on whose dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) is based the Emmy Award-winning eponymous television series. Commenting on how the screen adaptation has moved away from the original narrative, Atwood, speaking at the Hay Festival of Literature & Arts in Wales this May, said, “It’s a television series. If you’re going to have a series you can’t kill off the central character and you also can’t have the central character escape to safety in episode one of season two. It’s not going to happen.”

Novelist Marguerite Duras wrote the script for the film Hiroshima mon amour

Novelist Marguerite Duras wrote the script for the film Hiroshima mon amourAdmitting that she had no control over the television adaptation, she added, “I think I would have to be awfully stupid to resent it because things could have been so much worse… They have done a tippety-top job... the acting is great, they’ve stuck to the central set of premises.”

Adapting the same book for television and for cinema is also not quite the same process, thanks to the episodic nature of storytelling in the former. This was the case with Black Friday (2004), written and directed by Kashyap. Considered to be one of Kashyap’s best, the film won nominations at several international film festivals, and won him the Star Screen Award for Best Screenplay. “It was initially meant to be an investigative series on television, for Aaj Tak,” says Kashyap. “But that finally did not happen, and so it was transformed into a feature film.”

Kashyap’s recent directorial venture, Sacred Games, however, has the luxury of time; something that has suddenly been accorded to cinematic narratives by digital platforms such as Netflix. “Two and a half hours can be very limiting,” says Chopra, whose brother Vikram Chandra wrote the book on which Kashyap’s film is based. “Often, amazing literature cannot be fit into it. There isn’t enough scope to develop the characters and plots. And the experience is not immersive enough for the viewer. For these reasons, OTT [over-the-top] platforms are a wonderful option.” She also admits that the violence and language depicted in the story would not go past the Central Board of Film Certification. “The first scene itself would be not be cleared.”

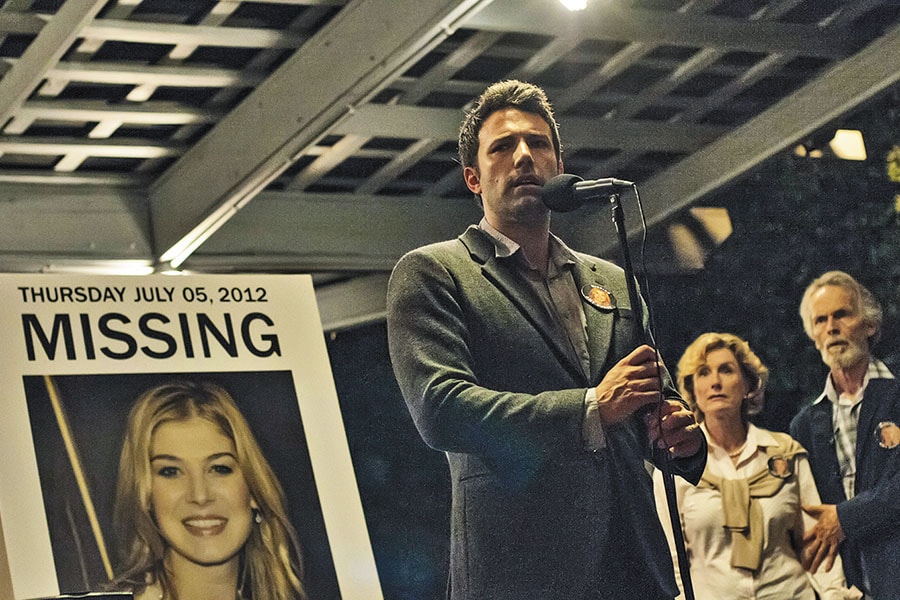

Gillian Flynn also wrote the screenplay for the film based on her 2012 book Gone Girl

Gillian Flynn also wrote the screenplay for the film based on her 2012 book Gone GirlImage: Twentieth Century Fox

Rao feels that although OTT platforms have definitely changed film watching habits, it is yet to be seen how it affects film writing. “They have opened up a whole new world and are changing how we look at written content,” she says. “They make it possible for stories not to fit a predetermined format. In such narratives, I would like to see the development of a character over time, with a lot more nuances, and more ambition.”

But if good films are to be made from good books, there have to be ways to get the twain to meet. “In India, the publishing industry and screenwriters inhabit very insular worlds,” says Chopra. “In Hollywood, they are joined at the hip.” And therefore you get a masterpiece like The Godfather (1972). For not only did Mario Puzo write the novel on which the film is based, he also co-wrote the screenplay with director Francis Ford Coppola, for which they won the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. The same is the case with Jaws (1975). Steven Spielberg’s thriller about a giant, man-eating great white shark is based on Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name, and on a screenplay co-written by Benchley.

This close association between literature and cinema did exist in India as well, with celebrated filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Bimal Ray, Govind Nihalani and Shyam Benegal adapting the works of equally masterful authors. But, in the last two decades or so, says Rao, we have moved away from good literature and good writers. “Discovering books and writers, too, is becoming an increasingly difficult job, what with disappearing bookshops. The linguistic diversity of India is another practical hurdle,” she adds. “There is so much written in regional literature, but we don’t have easy access to it in languages other than their original.”

“Bollywood does not treat writers very well,” says Chopra, adding that filmmaker Karan Johar’s announcement this August that hailed writers Hussain Haidry (dialogue) and Sumit Roy (screenplay, dialogue) as the “heartbeat and soul” of his next directorial venture Takht, “is an exception. But this should be the norm. The more we respect the writers, the better are the stories we will get.”

As audiences tire of formulaic productions and turn platform-agnostic, there is, therefore, hope.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X