Buy art because you want to live with it: Hugo Weihe

Hugo Weihe, CEO of Saffronart and a veteran auctioneer, talks about art as an investment option and how to avoid the pitfalls

Q. Since when did art become a serious and viable investment option?

I would look at it in a differentiated way and say that art has always been connected to money and power. If we think back to the Popes, during the Renaissance, they invested in the best artists to get the best kind of art. It added to social status and showed the world that they had arrived and that they were the ones in control. In that sense, there is an investment aspect in getting the best artists of the period to work for you.

Throughout history, there has been an understanding that art has a representative quality for a culture, and for a ruling class. The term investment is something I would look at in a multifaceted way.

Q. What are the different facets of seeing art as an investment?

In one way, it is the belief that art is an important aspect of humanity; it is something that is unique and handmade. It’s something that represents the culture you believe in, and your heritage. And you invest in it for that reason.

Q. In contemporary times, are there specific geographies where you see more of investments in art?

It has become a fairly global phenomenon. Historically, in America people would invest in art because there is a system where you can give to museums and get tax deductions; but it is also to leave a kind of legacy behind. So they acquired art once they had become successful in their careers and that was part of the investment.

People also bought art in the ’60s because there were artists they believed in, and also because they wanted something great on their walls. And now, 30 to 40 years later, they turn out to be superstars—like Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and others—and their value has exponentially increased. But some of those collectors didn’t buy because they were looking to make a huge kill; they bought because they loved the art.

That is the key to buying art—because it appeals to you, speaks to you; because you want to live with it. That will be good investment over time.

Q. Do you see the same approach to buying art in Europe?

I would say, historically, yes, it had a lot to do with social status. Generally, there has been a history of collecting and showing your friends that you have arrived. And they enjoyed it; there was a sense of cultivation behind it, cultivating an educated, well-rounded personality.

Q. What is the art market like in emerging economies like China and India?

There is something fresh about it. Historically, the Chinese emperors were fantastic collectors. And today, the moneyed can buy something that was made for a Chinese emperor a long time back. They thereby also raise the bar, in a sense, of their own status. In China, you also have an element of speculation in the market, certainly on the contemporary side, and art serves well as a store of alternative value and as an asset class. That has worked well, particularly in China, and probably in the US.

In India we are still very much at the beginning. I personally believe very highly in Indian culture and that things are dramatically undervalued in the scope of world art. And given the scarcity of a lot of material, such as of the great artists, it is hard to come by the real masterpieces. Over time, they are the ones that gain in value exponentially. With masters such as VS Gaitonde, SH Raza, MF Husain and Amrita Sher-Gil, we have the benefit of knowing that it is a concluded work, we know the entire oeuvre, we know what are the works that really stand out. Time has already told us what is important here; it is not much of a guess work. You already know that you are getting something great.

With contemporary art, it is not so clear which are the ones that are going to pan out, which are the ones that will really stay at the top, or climb to the top over time. So, it is more speculative in a sense.

Antiquities, to me, has been the most extraordinary opportunity that has been overlooked in India—the great Chola bronzes, the great Vijayanagara bronzes, the sculptures, the miniature paintings. These are India’s greatest heritage and have remained so untapped, and provide a great opportunity in terms of investment.

Q. How do Indians approach the idea of buying art, especially from auctions?

Auctions are a well-established practice. The good thing about auctions is that they are a completely democratic, open and transparent way of transacting. There is an under-bidder who is willing to bid almost as much as you. So that keeps the confirmation in the marketplace. Typically, collectors don’t know what the right value of something is. Even we, the seasoned ones in the business, don’t know what a masterpiece is really worth. The market will determine that.

The primary market is the gallery business. They ask a price for a contemporary young artist, and that is typically an affordable price below Rs 10 lakh. And that’s the starting point; we have to see where it goes from there.

The secondary market, the auction market, is totally democratic and market forces come into play. Auctioneers don’t own anything, we are agents. So we don’t promote anything over anything else in particular. We are happy to give open information about anything and I would advise collectors to ask us about everything. We will give the most objective advice.

Q. What are the things to keep in mind while buying art works?

I would look at the condition of something, and its rarity. Always compare with other works [of art]. You’ve got all sorts of tools now, you have the internet to do research. Look for similar work, made in the same year, in a similar size, how much does it cost, how important is it within artist circles, are there other important works in private collections, have there been exhibitions on this artist that help get international recognition? All these things count. In an auction catalogue we will provide all that information, we give as much historical context as we can. The provenance of the work is incredibly important; ideally you would want to trace it back to the artist.

Q. In India there are artists from relatively recent years. But in Europe, is it possible to trace paintings back to the artists?

If you are talking of artists of 100 or 200 years ago, it would be difficult. But for a lot of the leading artists, complete catalogues have been made of their entire works and often all the information on when they were first exhibited, who the previous owners were and the whole lineage of ownership are given. And that is what we are trying to establish in India too—catalogues to show as much history as possible. We have to do a lot of work to uncover all of this, and it is fascinating and really important. Sometimes, current owners don’t know the history of the art works they have, and we uncover all of it. But I can’t stress enough the importance of provenance.

Q. Why would you say provenance is so important?

The lineage of something is important. What is interesting over time is that the history and the context of a work of art always becomes significant. You want to be able to document, to say that the art work was shown at that particular exhibition, or belonged to that person, or it came directly from the artist at some point. All of that is relevant, objective documentation.

A work of art never just floats in space somewhere, it is always connected to people.

Q. What are the factors that influence the price of an art work?

Overall, it is not that black-and-white. Something that is outstanding within a category is what will stand out over time. Gaitonde’s canvases, for instance, are so scarce—we are talking about 200 or 300 canvases; and you also want to look at his best phase, whether it was the ’80s, and his early work is really rare and desirable; they would be rare within a certain category.

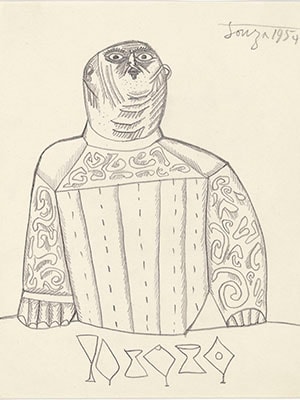

Then, say, [FN] Souza’s drawings will be a lot cheaper than his canvases; you can get it for a few lakhs, but some drawings can also be about Rs 50 lakh or so. Again, within that category [of drawings], if you get a 1955 drawing or so, then it is going to be something great.

If you are getting something of a master then it has a baseline value anyway, but you want to look at the best within that category. And you can do that by comparing and asking specialists in the field. There are objective ways of determining that.

Q. For artists like Gaitonde, whose art works are scarce, do prices go up if a lot of the art works are held in private collections and would not be available in the art market anytime soon?

Hundred percent. It is basically availability. It is demand and availability that, over time, will determine the price. The availability is dependent on those who take a long-term perspective and want to build a private collection or a private museum, which means the art work is not going to come back into the market anytime soon. It takes it out of circulation. It makes the remaining work in circulation that much rarer and that much more desirable.

Availability is incredibly important.

At the same time, the recognition that is given by an important museum or private collection also augments its status.

Q. So the Guggenheim Museum’s retrospective on Gaitonde in 2014-15 would push up prices for his art works.

Absolutely. It was a revelation for me. I knew a lot of those works, I knew where they were before. I had collected and sold them to new collectors in New York. But I was startled by how differently you look at the works when they are hanging on the Guggenheim’s walls in excellent company. And they looked absolutely stunning!

It was clear, again, to me that Gaitonde really stands up to anything in the world.

The same thing happened with Souza. He has not had a major retrospective yet, but when it happens, it will be very clear to everyone, to a much broader audience.

Q. What is the downside to buying art for investment?

Some people were taught a lesson in 2008 when the market crashed. And they had bought primarily in terms of pure speculation. It even left some of the art funds somewhere in storage.

My point would be, always buy art because it speaks to you, and because you want to live with it. So, buy it within your own budget and hang it on the wall at home, and enjoy it. That’s part of the dividend that you are getting from it every day.

And always buy the best you can afford. Don’t buy 10 lesser things; buy one good thing instead for the same money. And then you wouldn’t really have a downside.

Good art always holds up against time. There is no question about that.

Q. What advice would you give buyers?

Don’t ask 10 people and get 20 different opinions. Trust your eyes and your instincts. Buy what you love. But ask a few trusted advisors and friends, but not too many. Look for the provenance and the condition of the work. Look at it yourself. Always look at the art face to face, if you can. Spend time comparing, buy the relevant literature, go to the museum and exhibitions and see for yourself. You will always learn in the process.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)