Brews Going Native

Indigenous alcohol is seeking its place in the sun — and at duty free

Imagine a holiday in Goa without a glass of Feni, or trekking in the Darjeeling hills without a swig of Chhang. Impossible, isn’t it? Yet, ask an overseas traveller about his alcoholic beverage experience of India, or the local bottle he plans to pick up at duty-free, and you’re likely to be met with a blank stare. Or be offered the local beer/wine spiel.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. India’s indigenous alcohol count may not match its cuisines, but every region has its own unique brew. A variety of reasons has, however, constrained their growth: Forget exports, not one is widely available across India. As Mahesh Madhavan, CEO for Bacardi in India, says, “To become a national drink, [any beverage] has to be available in top bars across the country before it can aspire to be a global drink.”

Consider Cachaça, a sugarcane product, 99 per cent of which is consumed within Brazil, according to Nick Woodward, director, Northern Europe and Travel Retail, of Sagatiba Cachaça. Or Pisco, Chile’s famed wine, which is distilled from grape skins and pulp after the first pressing-production; 80 percent of this is drunk by the home market. Further up the growth curve, Mexico’s Tequila — after first nailing the domestic market — now sells an astounding 65 percent of its annual production of 200 million litres in exports, an indication of just how far local brews can go.

So what’s stopping desi alcohols from going pan-Indian, like idli-dosa, or rosogolla? Beverage consultant Yangdup Lama sums it up succinctly: “First, alcohol is not regarded as a dignified subject in India. Two, there is a general lack of knowledge about it.”

However, in spite of the lack of official patronage (with the exception of one state government), a few small beverage companies have successfully co-opted traditional categories such as whisky, rum and liqueurs, and applied uniquely Indian twists to them. Do they have the potential to go all the way and wow the world, like Tequila? Or will they score a hit with desi palates first? We pick the winners, factoring in popularity, uniqueness, history/heritage, availability, commercial prospects and the success of the cuisine that normally accompanies the brew.

Goa in a Bottle

By turns considered an aphrodisiac, a diuretic, a curative, a laxative and, finally, a must-try local product in Goa, Feni has indeed come a long way. With a base of cashew apples or coconut and bottled at 42.8 percent alcohol, Feni production is more elaborate than other indigenous alcohols’, with a fermentation time of up to four days and a double distillation process.

Its consumption, too, is more evolved than other spirits’. “Feni is a versatile drink. It’s aromatic and pungent, and so a bit powerful on the palate, but it works fabulously as a cocktail mix,” says bartender Shawn D’Souza.

Its consumption, too, is more evolved than other spirits’. “Feni is a versatile drink. It’s aromatic and pungent, and so a bit powerful on the palate, but it works fabulously as a cocktail mix,” says bartender Shawn D’Souza.

In Goa, the nutty, sweet Feni is commonly enjoyed with the famous spiced-and-smoked Portuguese-inspired sausage called chouriço. The meat is squeezed out of its casing into a ceramic bowl, poured over with Feni, and lit. If it catches fire easily, the Feni is of superior quality.

Almost all Goan restaurants, now have Feni-based cocktails. Says Bonny Perreira, partner of Martin’s Corner, Salcete, “In a day, we sell around 10-15 Martin’s Corner Special Cocktails, which uses palm Feni, pineapple juice, orange juice, Grenadine and Peach Schnapps. There definitely has been an increase in the sales over the past five years, as tourists find this a palatable way to consume Feni. We contract out the Feni production to a toddy tapper in our native village to ensure product quality and consistency.”

Accentuating the ‘apartness’ of Feni is the fact that it is the first Indian alcoholic beverage to possess a Geographical Indication (GI) registration, a sign that authentic Feni can only be sourced from Goa, catapulting it to the same league as Scotch, Champagne, Cognac and, closer home (and obviously non-alcoholic), Darjeeling Tea.

“There will not be a quantum leap in exports because of the GI status, but the certification will push Feni into the limelight of the global wine and spirits industry,” says Mac Vaz, president of the Goa Cashew Feni Distillers and Bottlers Association.

Potency: 42.8 percent

Travelability: High. As a distilled product, what you drink in Calangute is essentially what you can drink in Cuttack.

Tulleeho Rating: 6/10

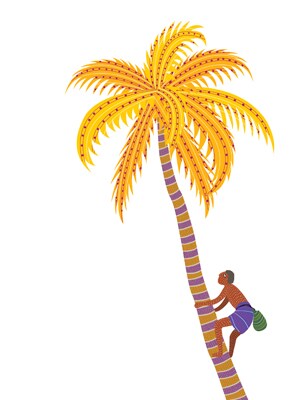

Talking Toddy

One of the simplest beverages around, toddy is as much part of the Kerala landscape as the backwaters and banana leaf-plates. In the early hours of the morning, toddy-tappers hitch up their mundus and clamber up date and coconut palms for pots of sap released by cut flowers. In contact with the yeast present naturally in the warm, humid air, the sap begins to ferment almost instantly. Once the process is complete, the toddy makes its way to the kallu shaap (read toddy shack), where it sells for Rs. 40 - Rs. 50 a bottle. Steamed tapioca and fried meats, heavy on pepper, accompany the toddy, the residual sweetness of the drink easing the burn-a-hole-in-the-mouth spicy food.

Despite its popularity, toddy has had no success outside its home state, partly because it is a freshly fermented beverage with a very low keeping quotient. Also, the image of the brew has received a blow from multiple cases of adulteration: Instead of making it more potent, the additives result in fatalities. In September, 23 people died because of the methyl alcohol added to their toddy in Malappuram.

Potency: 3-5 percent

Travelability: Low. As a freshly fermented beverage, it doesn’t keep well.

Tulleeho Rating: 6/10

Flower Power

They are the perfect gift for someone you love, they mark final rites and they brighten up our daily lives. In large swathes of central India, from Bihar to Maharashtra, flowers are also the base for potent brews. Tribals mix jaggery with the nectar-rich flowers of a common tree called Mahua and allow it to ferment before distilling it in crude copper stills. Like all indigenous liquors, it has a strong cultural connect with the lives of those who brew it, and is indispensable during celebrations.

Variations of flower brews are found in several other pockets of the country, including the north Bengal hills, where Grar Rakshi, made with local flowers chingping and rhododendrons, is popular with tourists.

Who knows, perhaps there’s a St Germain — an elderflower liqueur artisanale marketed around its seasonal availability in the French Alps — story waiting to be written here.

Potency: 20-25 percent

Travelability: High. A distilled beverage, Mahua can be enjoyed away from the heartland as well.

Tulleeho Rating: 5/10

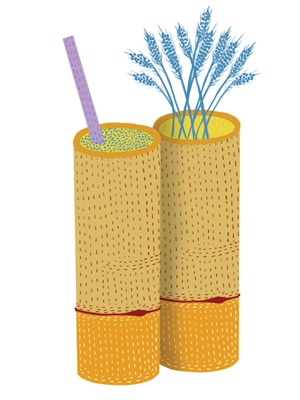

Peaks and Plains  Call it Chhang (as the Tibetans do), Thomba (Sikkimese) or Tongba (Nepali), this millet-based drink native to the Sikkim-Bhutan belt is also popular in and around Darjeeling. As the millet farms of the mountains give way to low-lying rice fields of the North-East, Apong is born as the favoured tipple in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. An integral part of the hard-scrabble tribal life, these beers are quite unique in their service: They are always drunk warm, with the exception of Apong, which is served at room temperature.

Call it Chhang (as the Tibetans do), Thomba (Sikkimese) or Tongba (Nepali), this millet-based drink native to the Sikkim-Bhutan belt is also popular in and around Darjeeling. As the millet farms of the mountains give way to low-lying rice fields of the North-East, Apong is born as the favoured tipple in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. An integral part of the hard-scrabble tribal life, these beers are quite unique in their service: They are always drunk warm, with the exception of Apong, which is served at room temperature.

Fermented millet is portioned out into bamboo glasses (dhungroo), topped with warm water and allowed to brew for 10-15 minutes before the malty, sweet beverage is sipped through a narrow bamboo pipe called the pipsing. Apong manufacture is similar: Bamboo baskets are lined with yam leaves, packed with rice and poured over with warm water. The liquid that trickles out — the process can take between six hours and a day, depending on the quantity of rice — is drawn off as Apong, sweet on the nose and malty, with an underlying smokiness. In summer, a chilli is added as a preservative.

Rice is also the base for Sekmai, a Manipur brew, and Handiya, popular in Jharkhand and Bengal. Distilled Handiya is known as Chullu.

In Sikkim and Arunachal, the usual accompaniments to these brews are animal offal: While the meat serves the whole family at dinner, the organs are fried and relished with a glass of Chhang or Apong.

Potency: 3-5 percent

Travelability: Low. Being freshly fermented brews (excluding Chullu), they don’t travel well.

Tulleeho Rating: 2/10

IMFL with a Twist

Of various experiments in the Indian Made Foreign Liquor category, including a paan liqueur, the three most interesting survivors are Amrut’s Single Malt, Rajasthan’s Royal Liqueurs and Le Rhum de Malabaricus. Tulleeho ratings are based on product category, company background, product vision, critical opinions and early scores.

Le Rhum de Malabaricus: The story of the birth of Le Rhum is as heady as the liquor itself. On a tour of a Dutch museum in 1999, Mohan Menon, a Kerala-based contract bottler for liquor majors, found two of his primary interests — colonial history and an ambition to create an Indian herb-and-spice-based liquor — stoked by a 17th century book Hortus Malabaricus. Written by Hendrik van Rheede, a Dutch governor of Cochin, it detailed the region’s rich herbal heritage. Menon spent six years creating a blend of rum that, while infused with local herbs and spices, maintains its identity.

The herbal rum is now available in parts of southern and western India, including Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Goa and Pondicherry, and in the UAE, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Nigeria and Angola. “About 70,000 cases of the 90,000 we produce are consumed by the home market,” says Gautom Menon, director of Gomovius AlcoBev, the company floated by Mohan Menon.

Gomovius has already extended the brand name to brandy and plans to launch an extension in the whisky category. “We have a few interesting bespoke products in the pipeline. We believe in only the niche market.”

Potency: 42.8 percent

Travelability: High.

Tulleeho Rating: 6/10

Royal Heritage Liqueurs from Rajasthan: If you thought innovation was the preserve of the private sector, meet Rajasthan State Ganga Nagar Sugar Mills Limited (RSGNSML). Beginning 2006, the state-owned corporation — which found an early backer in Maharaja Gaj Singh of Jodhpur — has introduced a range of exotic liqueurs based on recipes from royal families of the erstwhile princely states.

“The idea was to ensure that the recipes, which are part of Rajasthan’s heritage, did not die out,” says Jitendra Kumar, DGM at RSGNSML. The brands available are Royal Chandrhaas (from the Kanota family of Jaipur), Royal Jagmohan and Royal Kesar Kasturi (from the royal house of Marwar, Jodhpur thikana) and Royal Mawalin (from the royal house of Jodhpur, Sodawas thikana).

Apart from using original recipes with the stipulated ingredients (spices, dairy products, saffron, sugar, herbs), RSGNSML claims to adhere to the manufacturing processes favoured by the rulers/thikanedars in re-creating the liqueurs. The top-of-the-line products, priced between Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,300 a bottle, are available only in retail shops and select bars in Rajasthan.

Potency: 42.8 percent

Travelability: Fair. Needs to be consumed within a year.

Tulleeho Rating: 4/10

Amrut Single Malt. Like Malabaricus, Amrut Single Malt is the product of a mid-sized, home-grown beverage company, whose chairman, N.R. Jagdale, was fired with the idea of producing a mildly peated Indian single malt that would appeal to malt connoisseurs across the world. He achieved his goal in style when Jim Murray, whisky guru and author of the respected annual Whisky Bible, declared the Amrut Fusion Single Malt (a half-and-half blend of peated Scottish barley and unpeated Indian barley) the world’s third best single malt whisky in 2010.

“The biggest surprise package, at least for those who have never tasted the malt from this distillery before, was the whisky from Bangalore. It is not normally the first place you think of when you think of premier league distilleries, but Amrut is up there all right. However, this new version, Fusion, surprised even myself. It is one of those which commands a big mouthful, a chair with a headrest and silence,” Murray writes.

Small-group tastings — including blind tastings with other top single malts — have been key to building Amrut’s popularity around the world, paving the way for its availability in Belgium, Germany, Finland, Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the US, Canada, Japan, Australia, Singapore and Taiwan. Interestingly though, in India, it is available only in Karnataka: Blame the snobbish Indian consumer for this.

The way ahead for Amrut quite clearly lies in upscaling, with more single malt variants, but future plans include rum, sherry, brandy finishes for the single malt as well as something called Kadhambam, a combination of all three finishes. Now that it has achieved global renown, Amrut plans to make the product widely available in India.

Says London-based beverage consultant Tim Judge, “India has shaken up the whisky establishment with the incredible Amrut single malts from Bangalore. [It’s] proof that Indian producers can create world class spirits if they put their mind to it.”

Potency: 46 percent in India; 50 percent globally

Travelability: High

Tulleeho Rating: 8/10

Clearly, the upgraded IMFLs have all focused on niche, underserved categories, innovated with their product line-up and, in at least two of the cases, approached the overseas markets as a — if not the — primary consumer. Moreover, all these products come from comparatively small establishments, not major Indian or multi-national companies. With the exception of RSGNSML, which was lucky to start with tried-and-tested recipes, all the companies invested time in working out and refining the product formulation. In Amrut’s case, it led to a global endorsement.

Therefore, between indigenous brews and IMFL-with-a-twist, the latter may be considered to be in the lead for the moment. Going forward, however, if we had to pinpoint the ‘Product Most Likely to Succeed in Duty Free’, we’d still bet on Feni. In terms of potential, it ticks all the right boxes: It’s a white spirit indigenous to India, can be matured, bottled and stored, can potentially be made available at multiple price points and qualities and has excellent Indian and international awareness because of its synonymousness with the tourism-magnet state of Goa.

That said, a long road lies ahead of Feni producers. The two critical elements to take the beverage to the next stage, the industry agrees, are improved quality and focussed marketing efforts.

Says Judge, “From what I have seen and tasted, [Feni] is produced for minimum cost rather than best quality. While it could be more successful in Asian markets where spirits with a similar flavour profile exist — such as South Korea and China — the quality does need to improve. A recalculation of the ‘cut’ taken from the second distillation, experimentation with barrel aging, glass bottles and improved marketing are all necessary to elevate Feni to an international quality.”

Vaz adds, “Besides improving the quality, we need to increase cashew yield. Our production is constrained by the shortage of raw material.”

Quality is an area that probably calls for the authorities’ intervention. “The government needs to enforce quality metrics to regulate production,” says Desmond Nazareth, an upcoming beverage entrepreneur in Goa. “In a relatively unregulated production scenario — the kind one sees in India — there is plenty of scope for inconsistent products, some of which are actually injurious to health (e.g. because of high methanol content).”

While standardisation will convince consumers of the product viability, producers also need to step up the packaging if Feni — or any native brew — is to shed the dodgy ‘country liquor’ tag. Madhavan says, “To develop, a spirit category needs a lot of marketing power. It needs locally powerful brands to invest in creating the category through education and sampling. Feni also needs to associate itself with a ritual or one signature way to be drunk.”

In some ways, Feni today is at a stage that Tequila occupied a century ago. Feni producers could do worse than take a cue from Peter Gutierrez, managing director, Jose Cuervo, the world’s largest selling brand of Tequila. “Jose Cuervo is the trademark that pioneered the whole Tequila industry 250 years ago. Few know that we do things the way we always have. Authenticity, a sense of place, and a unique passion about what you are and the purpose you serve in the world are the key ingredients for sustainable success, in any market, developed or developing, East or West, North or South,” he says.

So here’s raising a ‘Feni-tastic’ toast to our desi brews, hoping that with time and the incorporation of superior marketing efforts and advancements in production technology, bottling, packaging and overall product quality, they will eventually become liquid ambassadors of the multifaceted cultures they represent.

Betting on Feni

Check all the boxes and Feni will fly

The Sagatiba Story

How a Cachaça brand from Brazil is hitting the big time

by Nick Woodward

Cachaça has been around in Brazil for over 400 years. The abundance of sugarcane, the raw material, and the simplicity of production made it the nation’s favourite spirit. Brazil produces around 1.3 billion litres of Cachaça a year; 99 percent of it is consumed locally. Taking this crude spirit to the international market was always going to be a challenge. We, at Sagatiba, knew the spirit had to be of a far higher quality to appeal at an international level. So, first we thought up a unique multi-distillation process to create a world-class spirit that was significantly better than the established national brands.

Second, we created a strong visual identity and iconic packaging, heavily influenced by the international premium white spirits market rather than the traditional Cachaça market (an approach since copied by other new entrants). Third, Sagatiba chose London as its launch pad due to the city’s global influence on the bar scene, fashion and music. The ‘success’ of the brand overseas helped sell Sagatiba to high-end bars in Rio and Sao Paulo, created desire for the product and justified the higher purchase price. Finally, Sagatiba is 100 percent Brazilian in its ownership, production, location — and this also helps reassure consumers that they are getting an authentic product.

The approach clearly worked: Sagatiba is now firmly established in both the international and Brazilian markets and is the world’s best selling premium Cachaça, with approximately 60 percent of sales coming from the home market (and primed to enjoy a surge of popularity with Brazil hosting the next FIFA World Cup and Olympic games). The same cannot be said for our competitors in the premium segment, who are mostly US-based and focus predominantly on the US market, with negligible sales in Brazil.

Nick Woodward is director, Northern Europe and Travel Retail, Sagatiba

The History

The making and consumption of alcohol in India can be traced to ancient religious practices and beliefs, while its evolution can be mapped with the political history of the country.

Some of the earliest references to cannabis, the leaves of which are used for making bhang, can be found in the Atharva Veda (2000-4000 BC). Worshippers of Shiva held it in great esteem as bhang was the preferred decoction of the deity.

Soma and sura were the two common alcoholic beverages in ancient India. While the consumption of soma — considered to be enlightening — was restricted to the elite, sura, a strong rice beer, was popular among the warrior class and the common man.

The tapping and consumption of toddy dates back to before the 8th century, when it was common among the Dravidians of southern India. The fermented beverage was made from the tapping of palm trees.

Under Islamic rule — between 1100 and 1800 — consumption of alcohol became part of court life, after initial puritanism.

Feni, closely associated with Goa, finds no mention in ancient Indian literature. The alcohol, made from coconut sap or cashew apples, is believed to have become part of the Goan culture in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Under British rule, the Europeans brought in their own spirits for their bureaucrats, elites and armed forces, although local alcohol from grains and fruits continued to thrive. To reduce import costs of alcohol, the first commercial distillery was set up in 1805 — Carew & Co. in Kanpur — to make rum for the army.

In independent India, the Prohibition Act severely restricted the manufacture and sale of liquor. It was only from the 1970s that the beer manufacturers started lobbying and there was an onslaught on indigenous alcoholic brews.

H.K Sharma is former research officer at the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences

Feni Facts

Cashew Feni is actually made from the cashew apple, not the nut.

Coconut Feni is distilled from coconut toddy.

The spirit obtained after the first distillation is called Urrack. The second distillation

produces Feni.

Before bottling, Feni is matured in miri wood casks for a few days.

Types of Toddy

Panam Kallu: Toddy made from date palm tree sap.

Thengin Kallu: Toddy made from coconut tree sap.

Elavan Kallu (4% alcohol): Toddy in its formative stage.

Mootha Kallu (5%-6% alcohol): Day-old toddy, slightly acidic with pronounced flavours.

Munthiri Kallu: Toddy with grapes added for sweetness.

- Improve product quality and consistency with government intervention.

- Increase varieties, from mass products to the artisanal.

- Highlight history and heritage.

- Get creative with packaging, branding, bottling and labelling.

- Shed the ‘country liquor’ tag.

- Create a drinking ritual, a la Tequila’s lick-the-salt, shoot-the-Tequila, suck-the-lime.

- Think up signature serves and cocktails.

- Popularise Goan cuisine: As the food travels, so will the spirit.

Vikram Achanta is co-founder and CEO, and Rohan Jelkie is Beverage and Training Manager, Tulleeho (tulleeho.com), a consulting and training services organisation working with the beverage and hospitality industry in India. The Tulleeho Cocktail Book is due for release by Westland Press in early 2011.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)