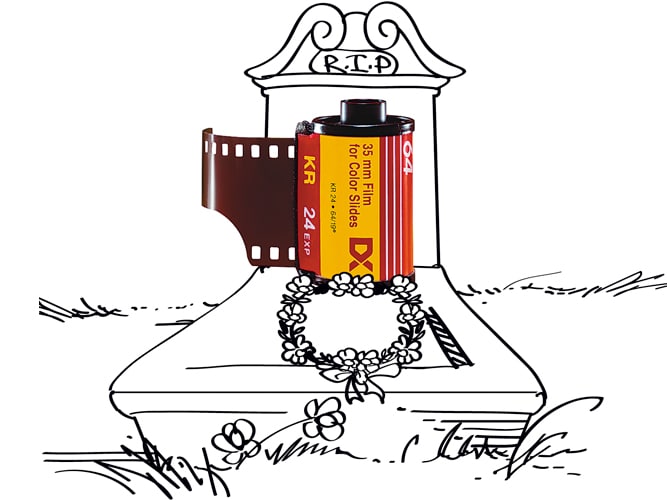

Take My Kodachrome Away

Forbes India’s director of photography isn’t shedding tears at the demise of the iconic film

When I heard that Kodak was closing production of its iconic film brand Kodachrome, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘Why did they wait this long?’

Sure, Kodachrome was the first choice for most professional photographers through most of the 20th century. And yes, for half that time, for any one wanting colour fidelity, Kodachrome 25 or 64 (ASA) was the answer.

From Steve McCurry — who shot the famous Afghan Girl picture for the cover of the National Geographic magazine among many other images — to Raghubir Singh, whose colour images of India adorn many permanent collections in the world, all the big names shot in Kodachrome.

That Kodachrome was intertwined with American popular culture was clear. Paul Simon’s eponymous 1973 song bears testament to that. And there’s even the Kodachrome Basin State Park, in Utah.

Kodachrome was cult. No contest.

But, all along, Kodak’s star product was carrying around the seeds of its own defeat. Its soft underbelly was that the film could only be processed using proprietary Kodak chemistry called K14. There were only a few, very select labs around the world that could do it. You would have to ship your film to these labs; if you happened to be in another city or country, delays were inevitable. Kodak got away with it because no other film even came close. Kodachrome transparencies were of archival quality; I don’t remember anybody complaining about the fading colours so common in the lesser transparency films of those days.

Then, in 1990, Fuji came out with a film called Velvia 50 that matched almost everything that Kodachrome offered. This, for me, was the beginning of the end of Kodachrome.

Velvia 50 attacked Kodachrome at two levels. It delivered good rendition of colours, very vivid, with good contrast, high image quality, just as good as Kodachrome. And the kicker was that processing was ‘open source’ — any good colour-processing lab that could process regular transparency film could do it. Even if you were hard to please on quality, you could find at least one lab in your city that could process Velvia 50 and have high quality transparencies ready in a day.

If you knew your way around a darkroom, you could process it yourself. I did, and the quality was always top draw. I definitely didn’t miss Kodachrome. But then, I learned my photography in the late 80s, and began shooting professionally in the 90s. Perhaps if I’d been a photographer before that, the film’s passing would have made me at least sigh a little.

Today, I’m a happy camper. 35mm Digital Cameras, and Imaging Software have broken film’s back, completely and irreparably. Digital SLRs, aided by high-megapixel full frame sensors shooting in the RAW format, with really fast processing capability, are in every pro photographer’s camera bag. I won’t even begin to get into how the digital era has finally made photography accessible to the amateur. In film’s heyday, it was always an expensive hobby to cultivate.

The digital medium offers many advantages; progress, after all, is inevitable. Film had to combat loyalty to glass plate negatives before its virtues became clear. Now, it must give way to sensors and pixels.

Kodachrome? Like its partners, the many iconic cameras — Leica’s famous rangefinders, or Nikon’s FM2, or Canon’s AE1 or any of the famous EOS models — it too must be laid to rest, its mission accomplished.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)