The Law of the Land

Buy land, they're not making it anymore, said Mark Twain. At last, India is moving to secure this basic source of human power

In modern history, Kurukshetra may be a small, impoverished town in Haryana with a feudatory subplot. But it was here that the mother of all land disputes was settled three thousand years ago, in an 18-day-long epic war of the Mahabharata. It is pertinent, then, that India’s most ambitious piece of land reforms ever should take shape here. A million battles more bitter than the historic one are raging in India’s courts right now, over disputed land ownerships. The underlying curse has been the lack of a clear and conclusive system of land titles, which opens up avenues for manipulation of records and stealing of property.

The early clues of how to resolve this mountain of conflicts is again coming from Kurukshetra. It is the first district in the country to prepare for ushering in the Torrens system of land titling that the central government plans to implement all over the country. A new law will replace the multitude of ancient and inefficient land record systems in vogue today with a uniform, nationwide system of computerised records. District officials in Kurukshetra have taken the first step by integrating the databases of the government’s revenue and land administration departments, a crucial requirement before the Torrens system can take over.

The overhaul of India’s land record system couldn’t have come earlier. The country is brimming with land disputes. A third of the 11 million civil cases pending in the lower courts involve fights over property. As much as 1.3 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) is locked away in such fights. Industrial projects worth $100 billion have been held up due to conflicts over acquiring land for them. Property tax collections account for just 0.24 percent of GDP, a third of the average for the developing world. All because India follows the outdated system of presumptive titling where ownership is established by tracing the history of transactions on a given property. The system has its origins in the practice of the British Empire to trace a property’s ownership all the way back to the time the monarch gifted it to a loyal subject. It is a complex, time-consuming affair prone to errors and hence disputes. And there is no king around to confirm such bequeaths lost in the timeless past.

That the new model could reduce that pain is evident from early experience in Kurukshetra. Complaints over land frauds — typically selling the same plot to several buyers — have come down drastically after land records were streamlined and put online, says the local magistrate, Pankaj Aggarwal. District officials have scanned about 200,000 documents covering 416 villages, collected maps showing all the land parcels and put the whole thing on a digital platform. Transactions are recorded with biometric security eliminating chances of identity theft. Villagers just walk into computer kiosks and download titles to the plots they wish to purchase, knowing these documents are the official, unadulterated version.

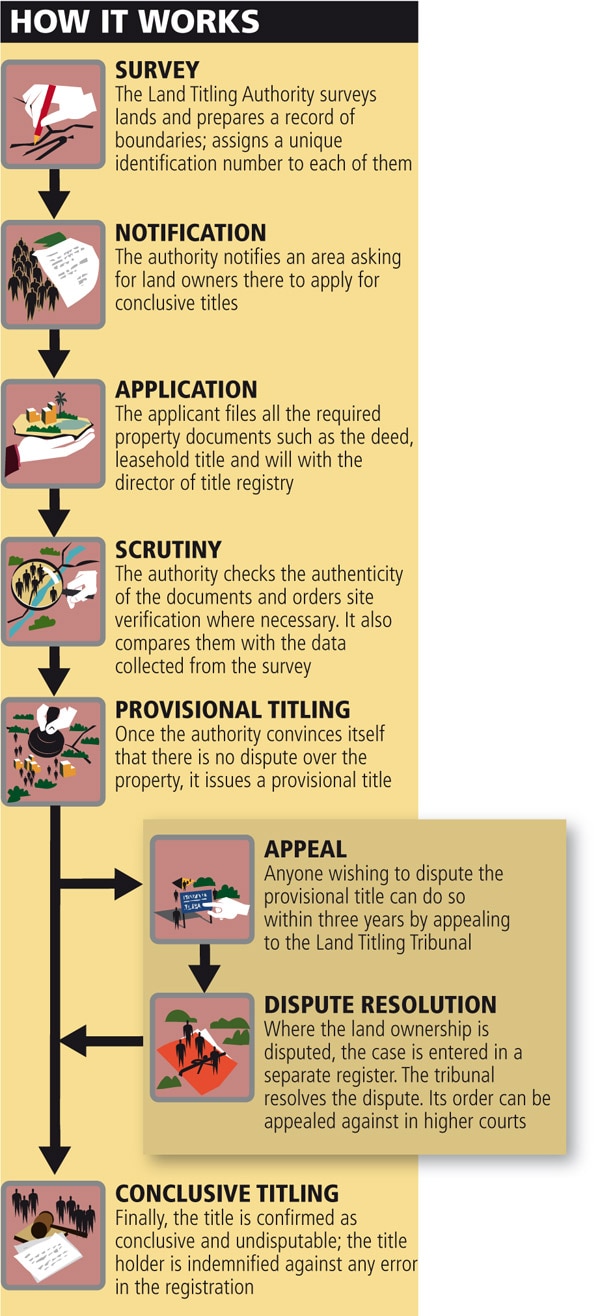

But what is set to happen is a matter far beyond mere computerisation. The government’s Land Titling Bill will bring about a fundamental shift in the way land records are made, kept and used in India. The old presumptive system will go. And with it, all the complex documentation about past transfers and encumbrance will vanish. It will be replaced by a single register of land titles for the entire country, conclusively establishing the names of current owners. Most importantly, it will come with explicit guarantee of the ownership which means casual and infructuous disputes that the old system encouraged will not be possible anymore. Genuine disputes could still be pursued but not before they have been considered by a tribunal to be set up by a new Land Titling Authority. The owners will also be insured against any error in the register. “It will make the process of understanding titles much easier and ensure that we don’t have property frauds,” says Keki M. Mistry, vice-chairman and CEO of Housing Development Finance Corp. (HDFC).

To ensure that level of credibility, the records should be made fool-proof. So the government plans to verify the details independently. “Ground truthing through aerial surveys will be done to verify the present land records,” says a rural development ministry official, speaking anonymously. “We are working on setting up ground control points to co-ordinate aerial surveys across the country to ensure verification of the land records,” the official says. About 2,500 such control points are being set up in the initial phase. About 42 million field measurement books and about 1 million village maps are also being digitised under the programme.

A Time-Tested Model

Sir Robert Richard Torrens was the premier of South Australia in the 1850s when speculative traders turned their attention to property deals. The British colony also had a confusing system of land grants. Torrens wanted to control speculation and also streamline the records of granted land. In 1858, he launched a single register of land records that succeeded in both these objectives.

But he faced enormous opposition. His political rivals as well as lawyers fearful of loss in income from this simpler system resisted change. But Torrens pushed the system through and evicted fake property owners. In time, the system spread to much of the Commonwealth and beyond.

In India, however, the reform has taken much longer. Land is primarily a state subject and each state follows its own method of record-keeping. Documents are in diverse languages. Instances of more than one person holding the papers for the same piece of land are common. Thousands of plots have no documents at all. As a result, land registration is often controlled by touts and bribe-seeking government clerks. A dangerous new trend was discovered recently when anonymous owners had bought land on the India-Pakistan border. On the other hand, tribal people are fighting after their lands, to the extent of one million acres across the nation, were taken away from them for development.

Implementing the Torrens system in this confusing mess will be an enormous challenge. India is a vast country with 640,000 villages, one-third of which have fewer than 500 people each. Many lack roads, electricity and water; so computers are out of question. “Paperwork is almost non-existent in such places. So establishing the current ownership would be a really difficult task,” says an executive who handles land acquisition for a large firm.

The Centre will need the states’ co-operation to push through the project. While Kurukshetra has made the farthest progress, 119 other districts are also working on preparing the groundwork for the new model. In 2008, the Centre launched the National Land Records Modernisation Programme which provides for computerisation of property records, carrying out surveys and training of staff. The total cost is Rs. 5,600 crore to which the Centre will contribute Rs. 3,100 crore. The balance will have to come from the states.

“This will be a mammoth exercise as the surveys will have to cover more than 140 million land owners, owning more than 430 million records in the rural areas. The exercise will also involve setting up of more than 2,000 ground control points that will help in carrying out aerial surveys across the country,” says Rita Sinha, land resources secretary in the rural development ministry. It will also involve training 100,000 land record officers (called patwaris) and 50,000 registration staff.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)