Asit Kotecha Helps Build Mumbai University's New Convention Centre

Asit Kotecha hopes to change the perception that Indian entrepreneurs don't donate to universities in India

Just inside the office of Pashmina Realty in Worli, there’s an entire wall covered by a poster of LIFE, an NGO (non-governmental organisation) whose Mumbai chapter focusses mainly on health, education and low-cost housing under the Asit Kotecha Foundation. The poster is full of slogans written by Pashmina employees who participate actively in the NGO.

Behind the poster wall is the office of Asit Kotecha, who owns Pashmina Realty and is founder of ASK Group, a financial and portfolio management services firm that advises wealth to the tune of $1.5 billion. Kotecha is not a new convert to giving; he’s been donating 10 percent of his profits to charity since the year his company was formed.

Asit and his younger brother Samir Kotecha founded ASK Group in 1983 to provide portfolio management and financial services and started giving away money to charity almost immediately, mainly in the areas of health and education. A large portion of the donation was routed through LIFE, which was managed by their cousins in Rajkot. Around 2005, they started the Mumbai chapter of LIFE under the Asit Kotecha Foundation. One of their biggest projects was the Habitat for Humanity, which provides housing for the poor.

But now Asit Kotecha is in the midst of his most ambitious giving project. A year ago, Kotecha donated Rs. 30 crore to the Mumbai University for building an international convention centre (ICC) at its Kalina campus and has now promised to bring in more funds as the cost of the centre has escalated to Rs. 200 crore.

“This amount is the biggest donation by any individual to any university in Maharashtra, if not India. Asit Kotecha has studied at Mumbai University. This donation will motivate some of the other alumni to come forward and participate in developing the university to achieve excellence and create a world class brand,” says Rajan Welukar, Vice Chancellor of Mumbai University.

Kotecha always had an eye for inflection points. Over the past 30 years, sectors like cement, auto, banking and steel went through regulatory and management changes that some companies managed better than others. Kotecha had a knack for identifying these companies long before the market realised their potential.

He got into Madras Cements in the late 1980s when the industry was decontrolled. The company was largely ignored by the market even though it had cash profits of Rs. 6 crore and a capacity of 12 million tonnes a year, one of the largest in the country. Kotecha got into the stock at Rs. 300 a share in 1989 and exited at Rs. 5,000 in 1992. He made similar killings in many other sectors, including two-wheelers and banks. He got into two-wheelers in the mid-1990s before others realised its potential and into PSU (public sector undertaking) banks when interest rates started to fall in early 2000.

Even with giving, Kotecha’s approach is pretty much the same. He’s looking for opportunities that can become inflection points for society, especially in education and healthcare. He firmly believes that education has the power to change societies.

“These are the areas where we get to see the change happening in front of our eyes. When this change touches the life of many people, it has a huge effect on society. Just like we see return on investment in a company, we like to look at the change that is caused by giving back to the society. It is the best return one can have. Asit is clear that the convention centre can cause a huge impact on Mumbai,” says Samir Kotecha who heads operations at ASK Group. His brother Asit is the strategist.

Indian promoters or CEOs have always preferred to give donations to universities abroad like Harvard or Stanford as they feel that Indian universities do not have the ability to utilise these funds well. Welukar wants to change all that and hopes Kotecha will become an example for other entrepreneurs.

When Kotecha first met Welukar in June 2010 at the university’s Fort campus to donate Rs. 3 crore for a new philosophy building in Kalina, he realised that things were different and Welukar, just a month into his job, was driving the change.

Thirty minutes into their meeting, when Welukar mentioned his dream of building one of the biggest convention centres at the Kalina campus, it didn’t take much time for Kotecha to agree to give Rs. 30 crore to the cause.

Universities across the world invest in convention centres as they help get international exposure and also attract talent. Welukar feels the ICC will create an environment conducive to innovation, research and learning as many international scientists and academic experts will come to the campus and inspire the students and faculty. Kotecha, on the other hand, looks at the impact on society when it comes to giving. He realised that the ICC was a landmark project with the potential to drive massive change.

For this project, the Kotechas have departed from their giving norms. Generally, they expect the beneficiary to contribute one-third of the project cost so that the owner gets a feeling of responsibility. But for the ICC, they overlooked this rule as the cost of the project is huge and there were multiple ways of getting it financed.

Another reason why the Kotechas are so keen on the ICC is that it will generate continuous funds for the Mumbai University as the convention centre will be free for at least four to six months in a year — when it’s not being used for education purposes — and can be lent out to companies.

The Convention Centre

In spite of being the financial capital of the country, Mumbai does not have a convention centre that can host 5,000 people. There were plans to build one at BKC (Bandra-Kurla Complex) but it never saw the light of day. Hyderabad has the biggest convention centre in the country.

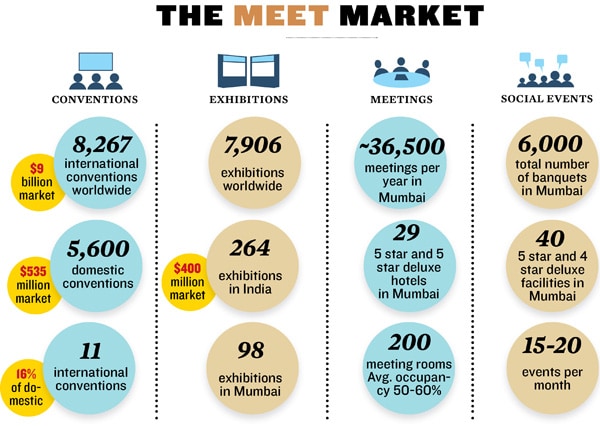

Organisations in Mumbai are forced to go to Delhi or Hyderabad to host large conventions, pushing up their costs dramatically. Delhi accounts for 29 percent of the share in the convention industry in India, while Mumbai accounts for 10 percent. Most of the conventions in Mumbai end up at JW Marriot, InterContinental The LaLiT or the Grand Hyatt, which cannot host more than 1,000 people at a time.

The Kalina campus is only 15 minutes away from the international airport, which makes it an ideal location for a convention centre. But what really works in favour of the plan is that India hosts numerous academic conferences and the ICC in Mumbai will easily be able to corner a large portion of the demand.

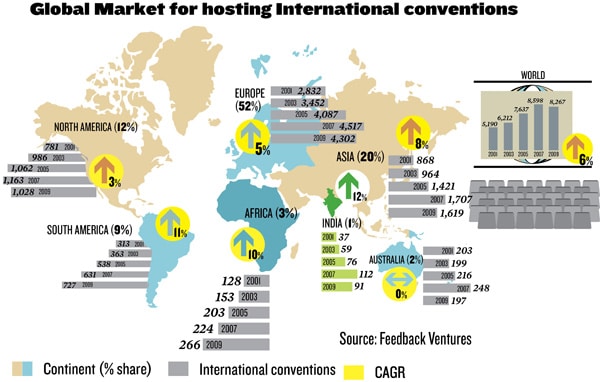

According to Feedback Ventures, globally, the convention centre industry is worth $106 billion and India is estimated to have a market size of $612 million, which will only expand in the future. Also, every rupee spent on the convention centre has the ability to give back Rs. 10 to the city by way of revenues and job generation.

When the project was initially discussed, the cost of building the ICC was pegged at about Rs. 50 crore. But after hiring Feedback Ventures as a consultant and some serious planning, the cost has gone up to Rs. 200 crore. There are seven architects fighting it out for getting their designs approved for the ICC. They will submit their designs this month (November 2011) and Kotecha will choose one and submit it to the university for approval.

Now, both the vice chancellor and Asit Kotecha are figuring out ways to fill the gap of almost Rs. 170 crore needed for the ICC. To begin with, they want some of the top business or political leaders who have studied in the university to come forward and make a donation.

Later, they want these corporate leaders to use their influence and get others to donate for the cause. There is also talk of initiating discussions with different banks to explain the importance of the ICC, so that they, in turn, can request their customers to make a donation. “Even if an individual is ready to give us Rs. 10,000 that will be great. It will be a completely mass funded convention centre and we can truly call it an amchi [our] Mumbai idea,” Kotecha says.

His other idea is to finance it like a corporate project where the contribution will be considered as equity and the rest as debt. He ideally wants to go with a 1:2 debt-equity ratio where equity is the Rs. 60 crore he expects to collect through contributions and about Rs. 130 crore is the debt. According to his calculations, it will take around six years for the university to clear off the debt, based on the revenues generated by the ICC.

Right now Kotecha has donated Rs. 30 crore, but depending on contributions from others he is ready to put in more of his personal wealth into this project.

The third way of financing the gap is to create space for international organisations like the United Nations or educational institutions and do a long-term rent agreement in advance for nine years.

But Asit Kotecha feels that the best bet is really to go to the common man who has studied at the university and ask him for donations. Every year around six-and-a-half lakh students pass out of the university. He believes that all of them will contribute for a good cause.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)