Why Do Artists Move to Abstracts?

For some artists the idea is central to their creation of canvases. It allows no room for either the familiar or the sentimental

In December last year, when Christie’s auctioned an Untitled painting by VS Gaitonde for a record-breaking Rs 23.7 crore , the world—and India—sat up to take notice of the artist who had largely been ignored in his lifetime. Over the years, his fame and market had grown, but only among the cognoscenti. For the average Indian, Gaitonde’s art was difficult to grasp because he did not paint in any recognisable form, the bulk of his estate consisting of colour palettes. Even though these appear luminescent, the result of intense layering, for the average viewer there is no central idea that fixes the image in their mind.

It is this that makes abstract art difficult for most people to relate to. A landscape or a portrait, a still-life, or a work of figurative narration that communicates a key episode, usually from history or mythology but also social situations, make up the bulk of modern art. Even within these genres, distortion can sometimes render them difficult to comprehend. So why does an artist move to the abstract? The primary idea here is to communicate something without giving the viewer anything tangible to hold on to. In the case of Akbar Padamsee, it was his “metascapes” or internalised landscapes. Gaitonde termed his art “non-representational” because it was intended to communicate nothing more than a canvas you could gaze at for its depth and play of colour. On these pages, the works of some of India’s leading artists lay out the richness and joy they stand for in the diverse ways they use to represent the idea of art that isn’t merely about replicating nature and the environment as it exists, but as it appears to them.

AMBADAS

Untitled, Oil on canvas

60” x 40”

A fearless abstractionist, Ambadas believed that colour alone had “character” and, therefore, he eliminated all representation in his art. Form wasn’t merely unnecessary, it was a hurdle in the pursuit of the extraordinary medley of colours that was for him the only component that mattered. For the viewer, what registered on his canvas clung to some tangents of a primitive memory, perhaps, of a dissolving universe, formations of the earth in massive transition, orbs of flames, or maybe vegetal remains, the interiors of human anatomy, riverine landscapes or a rapidly approaching cosmos.

A peer of the great modernists Tyeb Mehta, Akbar Padamsee and Mohan Samant, Ambadas formed the Group 1890 with J Swaminathan and Himmat Shah which, in its short life, influenced the thinking of an entire generation of artists, many of whom rejected figuration in their work. In many ways, his work and his life was part of his Gandhian philosophy that rejected materialism—perhaps the reason that his art too remained spartan and endowed, like him, with a suggestion of nature and spirituality.

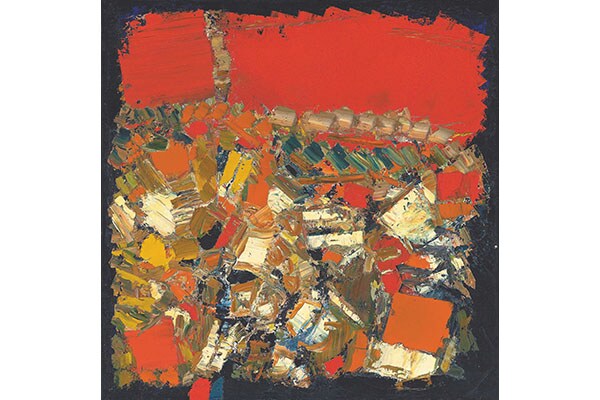

SH RAZA

Rajasthan I, Oil on canvas, 1961

19.6” x 19.8”

What can one say about an artist almost entirely associated with the bindu and the manadala, elements of Indian philosophy that are quintessential to his art from the 1980s onwards? Yet, Raza started out as a landscape artist in Bombay. From the ’50s to the ’70s, his work in France was inspired by American artist Mark Rothko’s “gestural abstraction”. He applied thick impastos to create abstract landscapes vibrant with colour, something he processed through an Indian sieve to arrive at a palate inspired by the Basohli miniatures with their crescendo of colours.

During this phase, Raza relinquished the necessity of imposing a form or structure in his paintings. Yet, they are expressive of places and moments, suggestive of his travels to Rajasthan and Saurashtra, both of which inspired him for the six decades he lived and worked in Paris before returning to India in the fall of his life.

AVINASH CHANDRA

Symbols, Oil on canvas, 1960

28.2” x 36”

Avinash Chandra was a bohemian artist who settled to paint in London in the exciting shadow of the hippie years. His experiments with the pop art genre at the time paralleled the huge success of FN Souza in the city. Like Souza, Chandra painted nudes, often in the shape of an orgy of floating limbs and breasts. Unlike Souza, he was also drawn to abstract shapes and forms. These appeared like hallucinogenic drawings, their unusual shape and form drawn from, but also differing from, popular imagery.

Unlike the major artists of the time, he was quite comfortable working with pen, watercolour, sketch pens and so on, drawing out the contorted lines in an amazing medley that proved impossible to decipher. Perhaps that is what his intention was—to move away from the recognisable to something that had the ability to excite, but without the burden of reality.

SHANTI DAVE

Untitled, Oil and encaustic on canvas, 1974

67” x 118.2”

To come across Shanti Dave’s work is like a blow to the gut, a breathless, evocative experience that leaves one feeling humbled. What is it that the artist imagined over his giant canvases, almost as though these were algorithms in relief of some cosmic sign language, a script of the ancients writ across space and given a living presence in encaustic high relief? It feels like a civilisation discovered, an alien landscape laid out before one’s eyes, a bird’s eye view of a world not ours.

A muralist, Shanti Dave combined Western expressionism with Indian metaphysics to elicit a response to his artworks arranged like a mystery in which calligraphy (but in no known etymological semantic) was central to the composition. Like hieroglyphics they command attention, the cryptic sea scrolls to his idea of an abstract painting in which forms and layers created areas of ingenuity and conversation. The abstract was no vague philosophy for him but rooted in something more tangible. What it communicated was, of course, left to the viewer’s rather more limited imagination.

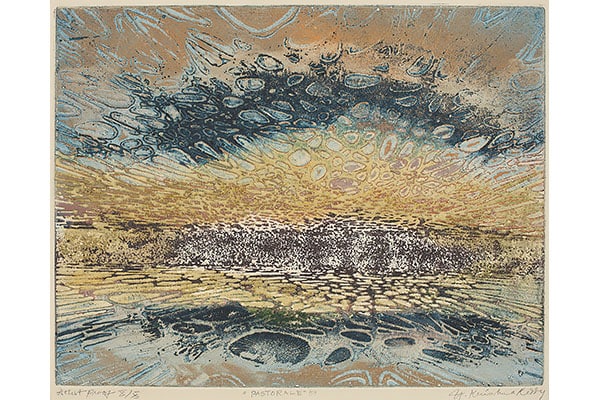

KRISHNA REDDY

Pastorale, Engraving printed in simultaneous process, 1959

14.7” x 18.7”

An accomplished printmaker, Krishna Reddy was associated with Atelier 17 and Samuel Hayter in Paris, which was not just one of the most important printmaking addresses in the world at the time, it was also where a large number of Indian artists came to learn printmaking. For them, Reddy was an inspiring teacher in intaglio printing not just for his skills and mentorship but also for the novel printmaking technique he developed for viscosity printing, using inks with different viscosities to do multiple colour print editions from deeply etched metal plates. This was less expensive than traditional methods of printmaking because it was able to combine different colours in a single plate with more pronounced results, even though they could surprise the less skilled artist.

Reddy’s palette of colours and instinctive grasp of the complex medium—printmaking is far more exhaustive than painting—saw him create a template of works that was almost cosmic in its orientation and contained within it the sense of infinitum.

ZARINA HASHMI

Untitled, Serigraph, 1971

23.1” x 17”

The artist Ram Kumar once said that to draw just one line on a blank page is more difficult than painting a canvas with a large variety of colours. He might have been speaking for Zarina Hashmi whose retrospective was recently held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. A printmaker with the bold ability to spin out entire narratives graphically, but briefly and concisely, Hashmi uses lines as a reference point, interlocuting them with barriers and boundaries, spilling the confusion and rage of the exile, the refugee, the immigrant in an elegantly sparse form that is nevertheless loaded with sentiment and emotion.

These lines are, for her, markers of geography. They are barriers and artificial divisions cutting off lands and people, confining rather than freeing races, a primeval scream against a society that does not heed the disenfranchised, and, in fact, establishes divisions even among the franchised. A student and admirer of both architecture and mathematics, Hashmi’s is a lone voice that represents the diaspora everywhere.

GANESH HALOI

Untitled, Oil on canvas, 1972

32” x 54”

The Calcutta artists were all influenced by the ubiquitous Bengal School, whether in little or large measure, not always in their choice of subject as much as their use of colour and the washed palette that was important to their rendering. Ganesh Haloi, a senior artist with the Archaeological Survey of India, hardly resisted that temptation, colour and light seeping through his paintings like something that is otherworldly. Perhaps it was what inspired him. Having witnessed cataclysmic events, both manmade and those that nature wreaked, he was drawn to the horrors and devastation caused by floods and the miseries it wrought on the unsuspecting and the innocent.

No wonder there is the suggestion of something underwater in his works, almost of a terrestrial world that has drowned, its reflections dredging up a ghostly memoir that has no mirror image but hints at things gone topsy-turvy in an imperfect universe. While critics have looked for meanings within this suspension of belief, others point to the truism that Haloi’s w ork needs no interpretation and can be enjoyed simply for their play of colours.

GR SANTOSH

GR SANTOSHUntitled, Oil on canvas, 1975

80” x 60”

Reconciling modern art with the ancient symbology of tantra was a great challenge for artists in the 1960s, which were heady years in a discovery of India that was more pop than real, and which rode the hippie wave. For GR Santosh, it wasn’t the international movement so much as an unexplained mystical experience in the cave of Amarnath that changed the course of his art, which hitherto had consisted of landscapes and cubist figurative paintings. Drawn to ancient philosophy—he claimed to have translated the Harappan script—Santosh created what has come to be defined as the neo-tantra school of art.

The crux of tantric art is balancing the energies of the male and female principles, an evangelistic communion in which man and woman, nature and human, yin and yang must be in complete harmony. The meeting of such energies results in a heightened spiritual experience. Santosh’s oeuvre has a recognisable figuration in which the intertwined limbs of the two principles are given a shape, thereby marking the torso and head. His paintings also accurately mirror the left and right of the image in a perfect reflection.

KCS PANICKER

Words & Symbols, Oil on canvas, 1968

26.5” x 33.5”

A seminal artist who founded the Cholamandal Artists’ Village outside Chennai, KCS Panicker might have been interpreting some philosophical treatise, if his work is any indication. Charts, logarithms and scripts suggest a ritualisation of humanity in an altered, alternate space. But look closely, and you will find that the symbols and words make nonsense of sense—or, perhaps, it is the other way round. If some of the ritual drawings look Egyptian, others are definitely Indian. The fish might be a biblical reference, the scales of justice a Western conceit, the astrological chart harking back to Vedic times, the colours symbolic of a stream of religious current running across cultures.

Yet, the script is merely representative, not a language at all; the pictograms have no logic or sequence. Was he being ironical, or was he running a narrative thread binding all nations and civilisations into a common structure of humanity? Or was he mocking our rituals and beliefs? There may be no answers, but this much is sufficient, that his work has a sense of urgency that is simultaneously compelling and alienating.

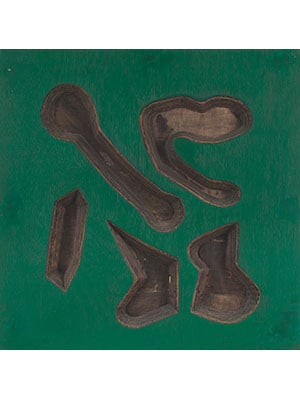

JERAM PATEL

Untitled, Enamel and blowtorch on wood, 2004

23.7” x 23.7”

If you are reading this, there is one term you will do well to learn the meaning of: Anthropomorphic. A member of the former Group 1890, Jeram Patel was drawn to forms that are an echo of terrains fashioned by nature over millennia, reminiscent of the gorges of ancient rivers, of howling winds and passing time. The natural weathering of the terrestrial that he recreates in a somewhat spontaneous gesture, is both painting and relief sculpture, but even his drawings display the layers and rings that mark the passage of years.

Patel’s works are deliberately crafted in a manner that is uniquely his. Taking sheets of plywood, he sticks them together to get a block of what resembles wood. He then burns deep through its surface with the help of a blowtorch, letting the force of the flame create its own shapes and rhythm—hence anthropomorphic. The result is a little like a raw, savaged world, wounded and bleeding, to which he applies a healing salve, clearing up the residue with a steel brush and bringing order and calmness in a new ancient landscape.

RAM KUMAR

Untitled, Oil on canvas, 1979

39.5” x 70”

Once upon a time Ram Kumar did some melancholic paintings of vagabonds in London, reflecting on their despondency. On his return to India, he discovered Banaras and began to paint its ghats in a bold outline of buildings—but that was for a brief period, for even then he had an abhorrence for any form that was recognisable. For him, all that mattered was the purely abstract, and once he began to paint in the style, he never once looked back. He concentrates only on recreating an intensity of colours, rejecting any suggestion of tree, sky, mountain or river.

Most of Ram Kumar’s works still centre around Banaras, though he has also been attracted to the barren landscapes of Ladakh. Yet, there is nothing discernible about these abstract scapes, and were it not for the titles of some of his paintings, one would not be able to tell a Banaras from a Ladakh. Is the blue in the painting a suggestion of the sky over the mountains, or the mighty Ganga on her way to the vast delta?

Your guess, really, is as good as his or mine.

(All images courtesy Delhi Art Gallery)

(This story appears in the March-April 2014 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)