Istanbul and the art of going on

In the tumultuous clamour and chaos that defines the city, even a riot can go unnoticed

“Istanbul seems to be burning,” I thought, congratulating myself on having come up with a piece of deathless prose. I had this minor epiphany while walking down Aynalı Çeşme Caddesi, a street in Old Istanbul that wears the city’s Byzantine and Ottoman heritage with pride.

‘Caddesi’ means ‘street’ in Turkish, and it was one of the first words I learnt during my stay in Turkey’s capital. The other phrase on my mind that evening was ‘adani durum’. Adani is a lamb kebab that I had grown fond of, and the durum (wrapped in bread) version of adani was my standard dinner. But on my second-last night in Istanbul, while tracking down the eatery that served my go-to delicacy, I inadvertently stumbled upon a riot being put down in the Kurdish section of the city.

I was walking towards the street corner where the kebab shop is located, salivating at the thought of biting into a warm adani durum. I should have been able to tell that something was off: People were moving in the opposite direction (towards me), and I had to keep swerving to avoid them. This isn’t too far out of the norm for Istanbul, though, which could explain how I missed the signs that something was not quite right. There was a burning odour in the air that was making my throat raw and eyes water. I had never encountered CS tear gas before, and it was only when I heard the popping of grenades and saw the smoke that I realised I was not going to be eating at my usual kebab place after all.

Looking back at it now, the riot seems impossibly tame. Yes, there were clouds of tear gas billowing out from the streets ahead as a helicopter hovered far above. And I could hear the wailing of sirens all around me. But in the background chaos that is Istanbul, even a riot can go unnoticed—until you’re almost in it.

I had been walking along quite oblivious to my surroundings, a coping mechanism that Istanbul with its clamour demands of you. For one, every mosque seems to run on a different clock. While the muezzins call out the adhan to bring the faithful to prayer, there’s always a slight overlap, with one or two leading the pack. The chorus leads all the other sounds in Istanbul, five times a day. In the gaps between, there’s the traffic. It’s far more chaotic than my native Mumbai had prepared me for. A bold, but accurate, claim.

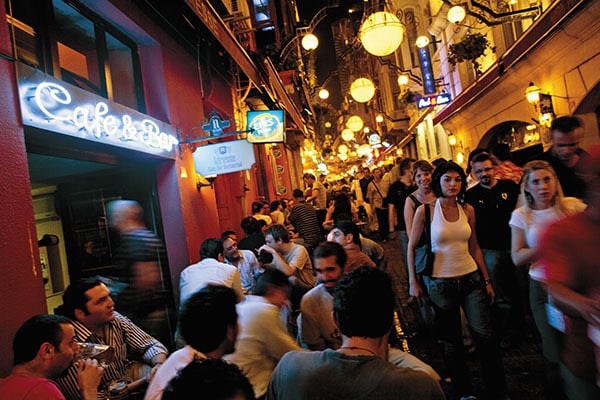

One must experience the night life in Istanbul which boasts of several bars and cafes

Istanbul, and particularly the Western, Occidental part of the city, is also full of music spilling out from nightclubs and bars, and the various instruments of street buskers and artists. Someone is always playing a loud tune wherever you go.

And finally, there are the colours: From the bright red of the million tiled rooftops that are visible from the air as you land, to the blue of the Bosphorus Strait reflected in the sky, to the myriad yellows, pinks and oranges of the buildings, shop fronts and stalls selling rice and lamb. Even at night, the lights are dazzling in their array of neon pinks and blues and the halogen yellow of streetlights. Hawkers, coffee sellers, ice cream vendors and earnest locals scurry about, all vying for your attention. There is so much visual and aural stimuli that the brain needs to shut down and concentrate on the more mundane tasks of walking about and putting food into the mouth.

Which is how I came to find myself, hungry and eager, clutching my 20 Turkish Lira, bound for the durum shop, when I realised that the Kurdish population centred in Beyoğlu decided to protest against Turkey’s lack of involvement in the ongoing ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) situation in neighbouring Syria. The police responded with tear gas and mass arrests.

The protesters were up in arms about the fact that Turkey was not going into Syria to rescue their fellow Kurds, trapped in the border town of Kobani. Controlled by the Kurdish forces after the start of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, Kobani has been held under siege by the ISIS since September 2014. As of November 2014, ISIS had gained control over the Western parts of the town.

Desperate for attention and outraged at the perceived Turkish apathy, Istanbul’s Kurds had been at boiling point for a while and, soon enough, the graffiti on the walls in Beyoğlu began to sprout requests for change and demands for action. The writing was on the wall, literally, calling for a large public demonstration, and I had walked by, completely oblivious. The paste-up posters and spray-painted manifestos of the Kurdish youth in Beyoğlu are their way of organising protests offline, a final reminder to the public to show up. Social media and Twitter, in particular, are far more effective at organising such events, but the graffiti is akin to a last message for those who may have missed the electronic summons.

Rich, a 32-year-old American expat who had lived in Beyoğlu for 14 months, explained this system to me. We met for the first time at a local grocery store, both of us buying milk to rinse the tear gas out of our eyes. Realising that we could just as easily share the milk, we struck up a conversation, and he told me about the local dynamic. “This is a pretty regular thing now,” he said. “The Kurds organise and get a protest going; the police break it all up with tear gas. There’s usually a fair bit of force used as well.”

The use of force in conflicts is not new to Istanbul. The city has been the site for riots, war, sieges and massacres for hundreds of years. As most crossroads towns will testify, the business of war is similar to the restaurant business: Location is everything. Istanbul’s unique position on the Silk Route, guarding the gateway to Asia and the East, has placed it in the cross hairs for almost every conqueror and would-be world dominator from the time of its inception in 667 BC as the Greek city of Byzantium. Under the Romans it was renamed Constantinople, which fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

The magnificent dome and chandeliers at the Hagia Sophia museum in Istanbul

Although there is no longer any large-scale warfare around the city, the signs of those turbulent times persist. The Hagia Sophia (pronounced ‘aya-sofia’) was once the world’s largest Christian cathedral, then a mosque, and now a museum.

Istanbul has flipped many times from Occidental to Oriental hands, and the art and architecture reflect this perfectly. Gothic cornices and buttresses coexist with Arabian domes and pillars and towers in an odd, but cohesive, pastiche.

Every aspect of Turkish culture is permeated with the after-effects of cultural clashes. To understand what the term ‘cultural mélange’ means, forget about Mumbai and New York City. Come to Turkey instead, and spend time in Istanbul. The city is a proverbial melting pot, filled with little lumps of anonymity clinging to its sides as the vast mass of humanity churns and swirls, exchanging values, vices and swapping traits and customs.

Despite the stinging in my eyes that testifies to the contrary, I am filled with hope on the way back home, that vastly different cultures can coexist in the same space. After World War I and the breakup of the Ottoman Empire into the Arab nations and Turkey, the once nomadic Kurds had no choice but to grow roots in these young countries. The CIA Factbook estimates that Kurds make up 18 percent of Turkey’s population. All the various tribes and nations that have made Istanbul their home, from the Greeks and Romans to the crusaders and the Arabian conquerors of Saladin, carved a space for themselves in Istanbul. And the Kurds, too, are fighting for that right.

India is currently undergoing its own clash of cultures between the East and West, traditional conservatism and iconoclastic modernism, and Turkey, with its strains of European and Arabian influences, is an interesting study. At the very least we should borrow some of the architecture and the food. Let’s leave the tear gas behind, though.

(This story appears in the Jan-Feb 2015 issue of ForbesLife India. To visit our Archives, click here.)