Rogan, copper, lacquer: A Kutch village's trifecta of timeless artistry

Nirona reverberates with the rhythmic clinks of hammers on copper, delicate brushes pirouetting across Rogan canvases, and the craftsmanship of lacquerware, all within a framework of sustainability

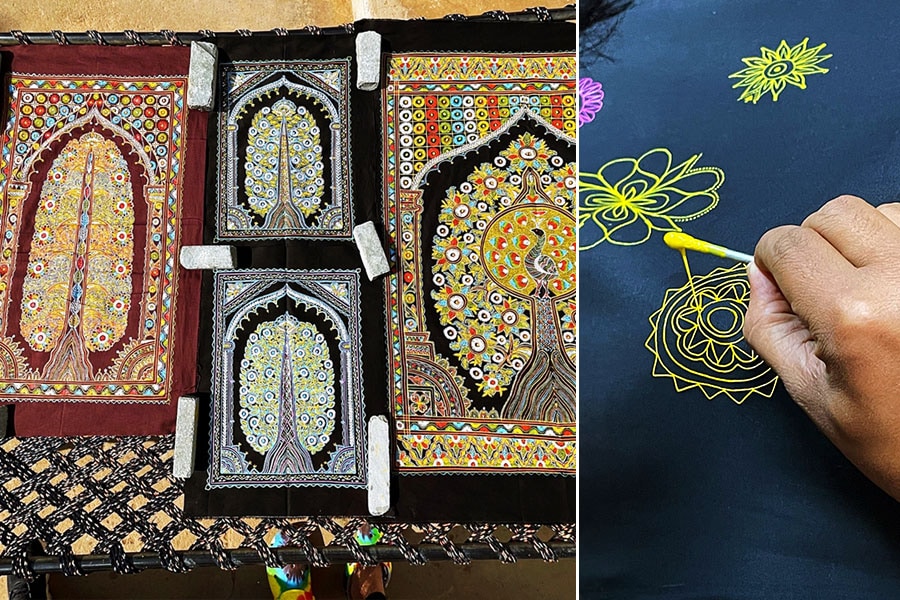

On the left - samples of Rogan art in Nirona Village. On the right - Artist Abdul Gafur shows us a variety of pre-painted Rogan designs.

On the left - samples of Rogan art in Nirona Village. On the right - Artist Abdul Gafur shows us a variety of pre-painted Rogan designs.

In the vast expanse of the Rann of Kutch, the ambience orchestrates an overture of salt and sun. It tingles on your skin, a stark contrast to the smooth immensity of the white desert stretched before you. Here, the horizon curves like a bleached bone, and the world feels amplified, every breath a tiny rebellion against the vastness. However, a vast legacy of art unfurls in vibrant threads beyond this timeless, moonlit ocean. Nirona, a village ensconced 75 km (47 miles) away from the white canvas of Kutch and the vibrant hustle of the annual Rann Utsav festival and a mere 100 km (62 miles) distant from the border's watchful eye, pulsates with the rhythm of timeless artistry.

Here, the air hums with the rhythmic clanks of copper hammers shaping exquisite crafts, sunlight dances on intricate Rogan paintings and lacquerware gleams with stories whispered through generations.

Along a dusty village lane, with sun-baked mud dwellings rising on either side, each doorway framed by a riot of colour, a wrought-iron gate painted a sombre black stands like a sentinel, with a rogue vine of bougainvillaea, like splashes of forbidden paint, trespassing from the next yard. Steeped in art, this house resonates with the echo of four centuries, where the Khatri family has held aloft the torch of Rogan painting, India's sole inheritor of this award-winning tradition.

“In Persian, the term Rogan signifies oil-based,” says Abdul Gafur Khatri (58), recipient of the Padma Shri award, eight state-level awards, five national awards, and even an international designer honour, about this art form that can be traced back to Iran. “Hailing from Iran, my family relocated to India almost four hundred years ago. Over time, we managed to uniquely tailor the Rogan art form, making it a distinctive specialty of Nirona. We proudly stand as the sole guardians of keeping the Rogan art alive for eight generations,” he adds.

Meet Abdul Gafur Khatri's family. Khatri family has held aloft the torch of Rogan painting, India's sole inheritor of this award-winning tradition.

Meet Abdul Gafur Khatri's family. Khatri family has held aloft the torch of Rogan painting, India's sole inheritor of this award-winning tradition.