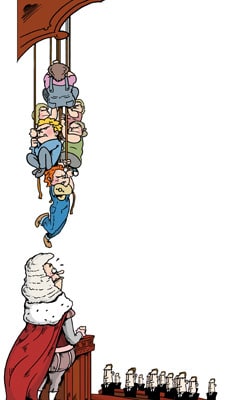

Fall of The House of Lords

Democracy, dignity and debauchery co-existed peacefully at The House of Lords

Great Britain struggles more than any other country to let go of medieval pomp and ceremony. Burdened by a millennium-long obsession with prim and proper behaviour, the English have developed an admirable tolerance of anachronisms. So, when they talk of abolishing the House of Lords — that fountainhead of ritual that has kept alive the concept of hereditary nobility of men and the wearing of breeches and wigs well into the 21st Century — it is hard not to take notice.

Not that the idea of doing away with the Upper House of British Parliament is new. As early as in 1649, at the height of the English Civil War, the House of Commons controlled by Parliamentary leader Oliver Cromwell declared that “The House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England.” Cromwell & co. executed King Charles I, abolished the monarchy and formed a republic. But just a decade later, both the monarchy and the House of Lords made a decisive comeback.

The British Parliament has its origins in the Anglo-Saxon practice of the 11th Century when religious leaders and trade magnates were invited to advise the king on tax and governance matters. It took another three centuries for the Parliament to become bicameral. The council and shire leaders sat separately in what became the House of Commons; the Lords Spiritual (clerics) and the Lords Temporal (influential people) sat in a smaller, but much better furnished House of Lords.

The British Parliament has its origins in the Anglo-Saxon practice of the 11th Century when religious leaders and trade magnates were invited to advise the king on tax and governance matters. It took another three centuries for the Parliament to become bicameral. The council and shire leaders sat separately in what became the House of Commons; the Lords Spiritual (clerics) and the Lords Temporal (influential people) sat in a smaller, but much better furnished House of Lords.

As impulses of democracy spread, the inevitable power struggle between Parliament and the monarchs ensued. Even in 1215, King John had been forced to sign Magna Carta, or the Great Charter, that established the rights of people and the notion that even the king was bound by the rule of law.

Even though the Lords gradually lost its primacy to the Commons, its importance as the keeper of England’s traditions and as the anchor for democracy never once diminished. But that is not to say that the Upper House never had its colourful, playful moments.

The year 1988 was a turbulent and divisive one in British history. Half the nation opposed Margaret Thatcher’s legislation banning the “promotion of homosexuality” which effectively meant even a teacher’s counsel to a gay teenager was rendered illegal. Protests erupted everywhere. They reached the pristine House of Lords too. One day, as the lords rested their morally upright backsides on the red leather, lesbian women climbed down on ropes from the public gallery shouting for the abolition of the impugned law. It was quite a sight with the Lord Chancellor with his knee-length pants and flowing artificial hair pondering on the one side and the rebellious lesbians hanging above and hollering from the other.

Many occupants of those chairs have handled more excitement than that. Lord Hugh Despenser the Younger was apparently the homosexual lover of King Edward II, but was also a land grabber and pirate. Queen Isabella, perhaps to stop him from competing with her for her husband, got him executed, but not before getting his genitals cut and thrown to fire. Lord Lawrence Shirley (1745-1760) had four illegitimate daughters and one teenage wife. He was executed for murder.

The heat will be on similar councils elsewhere. In 2006, a study estimated that it cost Rs. 67 lakh to run India’s Parliament for a day, though half of its time got drowned in slogan shouting and walkouts. With 40 percent of that money spent on Rajya Sabha, where failed politicians and party donors often find refuge, the taxpayer may soon question its relevance.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)