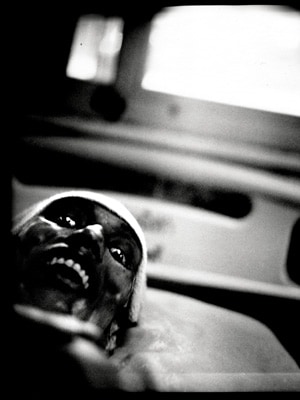

Aids at 30 - Down But Not Out

Thirty years after being identified, the HIV infection rate has declined, but when will we have a vaccine to nail the virus?

It has been 30 years since AIDS, one of the most-feared epidemics of our times, was identified. From 1981, when the first case of AIDS was reported from Los Angeles, US, — in India, the first case was detected in Chennai in 1986 — to 2011, when 34 million still live with this infection and 7,000 get infected every day, the story of this deadly virus reads almost like a crime thriller.

A virus turns rogue, jumps from chimps to humans, and stays dormant for several decades before it starts infecting humans, brutally attacking their immune system. It then holds the global medical and scientific community to ransom for close to a decade when finally some breakthrough is achieved in the late 1980s as drug companies launch a cocktail of medicines. Recently, mercifully, the plot hasn’t thickened. The coming together of philanthropic organisations, governments, pharmaceutical companies, etc. ensured that focus on the pandemic remained sharp. Therefore, the world, in general, and India in particular, is making progress against this epidemic.

According to the latest data from the National AIDS Control Organisation, released in December 2010, the number of new HIV infections from 2000 to 2009 declined by 50 percent. An estimated 1.8 lakh people caught new HIV infections in 2009 compared to 2.7 lakh in 2000. “This is impressive control, but there’s no time for complacency. Some regions in India are showing increasing incidence,” says Ramesh S. Paranjape, director of the National AIDS Research Institute in Pune.

Even globally, the infection rates have declined; killing 1.8 million people every year, down from 2.2 million from its peak in 2005. Says Dr. Rajat Goyal, country director, India, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI). “We now have in hand proof-of-concept for all of the major biomedical strategies for blocking HIV infection — including a vaccine.”

In India, at least 60 collaborative initiatives are currently on for all these strategies. Moreover, a recent large HIV Prevention Trials Network study, where India also participated, showed that administering the existing anti-retroviral drugs universally, even to infected people not showing AIDS symptoms, prevented infection transmission by 96 percent. This indeed looks a good preventive mechanism, but providing drugs for long and for millions is a logistical and financial challenge, particularly now when international donors are cutting down their contributions.

If no more twists come in the plot, a vaccine would one day nail the virus. Will it take another 30 years?

The polio vaccine was introduced to the public a full 47 years after the virus responsible for the disease had been identified, says Dr. Goyal. “As for the AIDS vaccine development timeline, most researchers agree that it is no longer a question of whether we will have an AIDS vaccine, but when.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)