Protecting Against The Pirates of Bollywood

A potential link between the disappointing box-office receipts and intellectual property (IP) law

In 2007, Sony Pictures became the first multinational studio to enter the India film business known as Bollywood with its $7 million film Saawariya. The movie grossed only $9 million. That same year, Walt Disney Pictures collaborated with Yash Raj Studios, one of India's leading production houses, to make the $3.5 million Roadside Romeo. The first-of-its-kind animated Hindi movie barely broke even.

All told, Hollywood studios invested an estimated $100 million on producing films in India between 2007 and 2009. But box-office profits were hard to come by, despite the power of India's growing middle class, and the fact that India's film industry sold 3.2 billion tickets in 2009.

Harvard Business School Associate Professor Lakshmi Iyer, a native of New Delhi, was intrigued by Hollywood's failures, especially considering American films had made great inroads in other countries. So she started to investigate a potential link between the disappointing box-office receipts and intellectual property (IP) law.

In the case study Hollywood in India: Protecting Intellectual Property, Iyer and HBS India Research Center researcher Namrata Arora uncover a complicated mix of piracy and plagiarism that harm not only Hollywood's efforts at success in the Indian market, but local Bollywood companies as well. Iyer says the case can help students and practitioners understand the best business strategies for firms to protect their intellectual property rights—one of the most important growth drivers in the US economy—in developing markets.

The case is one of a series Iyer is developing that are linked to property rights in emerging economies. Other case studies include an analysis of slum redevelopment in Mumbai, and an ongoing investigation of the transfer of land from agricultural to industrial use in China.

Pirates on the horizon

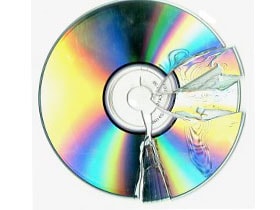

There are two primary types of IP theft for copyright industries, which include movies, music, books, and software. Piracy—the illegal copying and distribution of movies—represents an estimated loss to music and movie companies of up to $180 million a year in India. Plagiarism-—making films based on the ideas, plots, characters, and other "inspirations" from famous films—results in an uncalculated loss in royalties to the original writers and performers, and can weaken IP protections for others if not enforced.

The case meets up with Vijay Singh, CEO of Fox Star Studios, to discuss a strategy for protecting IP on the upcoming release of My Name is Khan in February 2010. Fox Star, a joint venture between Hollywood's 20th Century Fox and Asia's STAR Television (both owned by Rupert Murdoch's News Corp.), paid in excess of $22 million to acquire the film's global distribution rights.

Students are asked to make some of the same cost-to-benefit analyses considered by Singh and his team:

Should the mass-market price of DVDs be lowered from $5 or $10 to $1 or $2, which would match prices charged by pirates? After examining the numbers, Iyer says students understand that selling low is a losing strategy. "They take such a loss [on the profit margin] that the extra sales don't make up for it."

Should a single release date be used for global distribution, instead of a staggered release? By the time Fox Star Studios released Danny Boyle's megahit Slumdog Millionaire in India, several months after its US release, most people there had already seen pirated versions. To answer this problem, a distributor could choose a single worldwide release date. Doing so, however, would negate cost savings achieved by reusing film copies across staggered release dates. Studios could also limit a film's distribution to digital, not analog, screens, the copies tagged with electronic watermarks so forgers could be traced—but there are very few digital screens in India. With movie tickets in the country selling for only 57 cents on average, and a digital screen costing $150,000, installing one usually doesn't make economic sense for theaters.

Should local theater owners be prosecuted for running pirated prints? Iyer says going to court is a long and complicated process, with outcomes uncertain at best. For instance, it can be difficult to successfully prosecute a theater owner if someone sneaks in and makes an unauthorized camcorder recording.

Should studios go after Internet pirates? "Movie piracy in India is rampant—you can get one online the day after a release," says Iyer. To police pirated copies online, a Hollywood company could pay $100,000 to hire 50 monitors after a debut. But if 350,000 people are prevented from illegally downloading one movie, and instead pay 57 cents to see the movie at a theater, is it worth the cost? Yes, it probably would be worth it, she says.

Should Hollywood sue Bollywood production houses to fight plagiarism? This bet can be a lost cause for American studios. After showing a couple of scenes of the Bollywood version of the Will Smith movie Hitch, it was obvious to Iyer's students that it was a knockoff. But they were divided, just as India's courts have been, about whether what they watched was plagiarism. The words used in Bollywood films are different, and India's theatergoers perceive the movie's dialogue differently than US audiences, students observed. And India's copyright law, similar to the law in the United States, lacks a clear dividing line that defines plagiarism. "The ambiguity is inherent in the product," Iyer says, making it difficult for Hollywood to collect anything in the courts when its scripts are stolen.

Getting it right

Despite the formidable challenges, Iyer found that Hollywood's efforts in India are far from a lost cause, noting that all these problems can be addressed if a studio understands India and develops a coherent strategy, as did Fox Star Studios. After some effort, Iyer persuaded Fox Star execs to open up about how they succeeded in producing and distributing My Name is Khan in the country. The first thing Fox did right? "They set up shop in India."

The company's previous release of the Hollywood blockbuster Avatar to the Indian market created the blueprint. Fox Star aggressively distributed the film to over 700 screens and dubbed it in three regional languages. Then, when the company introduced My Name is Khan, it put both money and power behind the release. "It's going to be released in a way no Hindi film has been released internationally before," the film's star, Shah Rukh Khan, says in the case.

First, CEO Singh took steps to keep Khan prints out of the hands of movie thieves. To prevent hijacking of copies heading to theaters, a Fox Star employee accompanied every analog reel released in theaters in India and abroad. The studio also hired antipiracy agencies across India that worked with local police to raid illegal DVD-making facilities in the days following the film's release. (The Mumbai police alone seized over 3,000 pirated DVDs of My Name is Khan on February 18, 2010.)

To battle illegal distribution over the web, Fox Star hired three agencies that specialized in online crime, with one agency targeting Internet users in India and two focused on foreign users. The agencies identified and shut down 11,000 online links.

A single global release date further helped thwart online piracy. "By having a universal release date, we helped reduce the temptation faced by our global audiences who were eager to watch the film as soon as it was released in India," case protagonist Rohit Sharma, head of international sales and distribution at Fox Star, says in the case.

Happy ending

The end result was a major success at the box office, both in India and internationally. Industry sources estimate the movie, which cost $22 million for Fox Star to acquire, earned more than $40 million—one of the top 10 highest-grossing Bollywood films of the past decade. Khan also succeeded on DVD, and according to industry reports, Fox Star sold the film's Indian satellite television rights to Star India Private Limited for a record $3.3 million.

Iyer saw My Name is Khan, a love story whose autistic lead character is frequently compared to the one in the American film Forrest Gump, as part of her research. "It is a well-made movie with great actors," she says. "I thought it was a little melodramatic toward the end, but I quite enjoyed it."

This article was provided with permission from Harvard Business School Working Knowledge.