Can art and craft drive the message of climate change home?

Artists and designers are using their craft to raise awareness about pressing environmental issues, often with a touch of humour

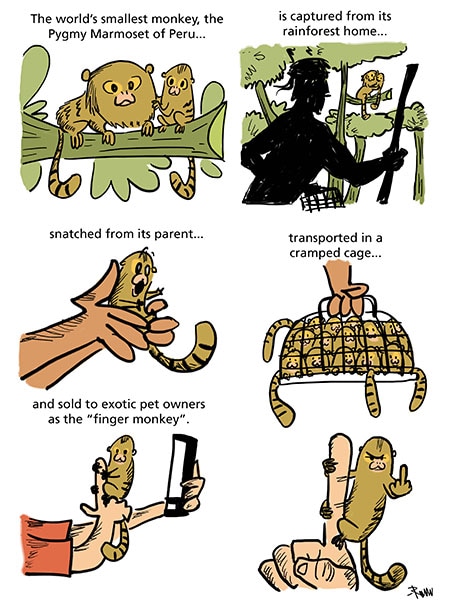

Cartoon strips by Rohan Chakravarty create social impact

Cartoon strips by Rohan Chakravarty create social impact

From a grizzled squirrel pondering over its own obituary in the likelihood of a dam being built in its sanctuary, to a bee reading out a manifesto of doom, cartoonist Rohan Chakravarty, fuses art with humour to draw attention to pressing environmental matters. Marine biologist Gaurav Patil, creates illustrations that bring to life the plethora of creatures found along India’s vast coastline—from extra-terrestrial-like sea angels to commonly found zebra sharks.

Chakravarty and Patil are part of a breed of artists, designers and illustrators across India who are working to demystify scientific jargon, and foster awareness and interest in creatures and habitats that need immediate attention. Although these artists are driven by different motivations, a deep passion for the natural world is common to all; for some there is a strong personal connect with the wild right from childhood, while for others the interest has grown over time.

Growing up on a steady diet of wildlife documentaries, Akshaya Zachariah was always clear about wanting to work with animals. When her dreams of becoming a veterinarian didn’t materialise, she chose to pursue design studies. “Being an artist helped me come back into the conservation space and use my voice,” she says. Like her, Deborshee Gogoi, a professor who moonlights as a wildlife illustrator, had forged a strong relationship with the wild as a child. Growing up in Assam’s Tinsukia town, the Bherjan forests was his playground.

In Chakravarty’s case it was his grandfather who instilled in him a fascination and appreciation for wild animals. That interest lay dormant till he encountered his first tigress in Nagzira Tiger Reserve as a college student pursuing dentistry. The sighting brought about the realisation that wildlife was his calling.

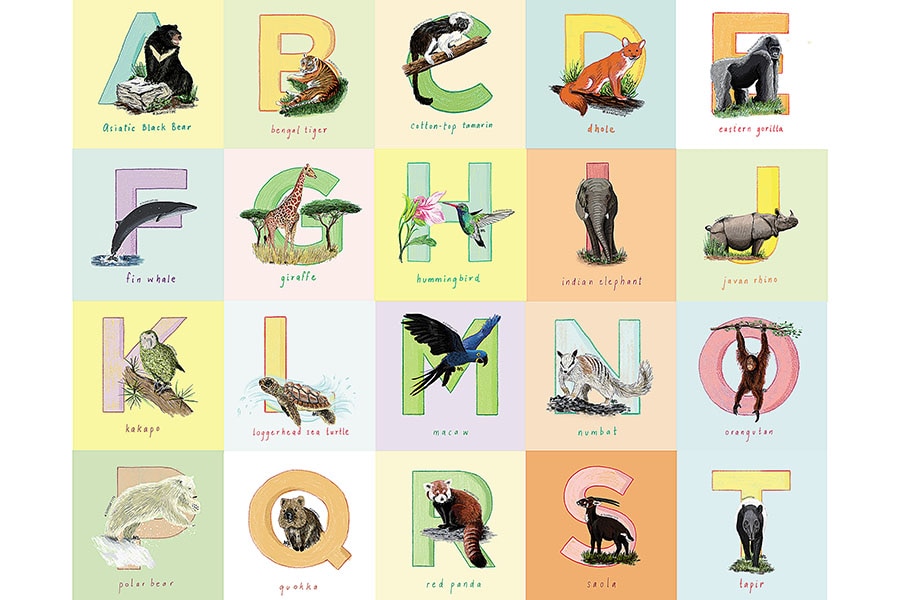

Akshaya Zachariah interpreted English alphabets by illustrating endangered species

Akshaya Zachariah interpreted English alphabets by illustrating endangered speciesDesigners Ashvini Menon and Sudarshan Shaw struck upon their calling while pursuing their higher studies. As a student at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, Menon’s projects invariably revolved around wildlife. While working with the Ahmedabad Zoo to create their signage, she got a ringside view of how people interact with animals. “People have a constant need for entertainment, often at the cost of animals,” she says. After a stint with Microsoft India as a user experience designer, she set up her own studio. “There came a point when I didn’t want to wait any longer to work in the conservation space,” she says. Visual designer Shaw was exploring topics for his graduation project at the National Institute of Fashion Technology, New Delhi, when he interacted with several wildlife enthusiasts, communities living in and around forests and people working with forest departments.Through their guidance he realised that his interest lay in wildlife, and that’s what he should pursue.

Despite their varying backgrounds, what is common to these artists is their belief in the power of imagery to bring about change. They communicate through comic strips, maps, murals, coffee table books, children’s books or memorabilia.

“Creative means of disseminating information around conservation issues was missing, and that’s the gap I wanted to fill,” says Chakravarty. This led to the birth of Green Humour, a series of cartoons, comics and illustrations. After the success of his first solo exhibition in 2014, Chakravarty turned to cartooning full time, and began regularly contributing to newspapers. “The human mind is accustomed to not just retain but also respond to information presented visually. When that visual is humorous, the communication progresses to a handshake,” he adds.

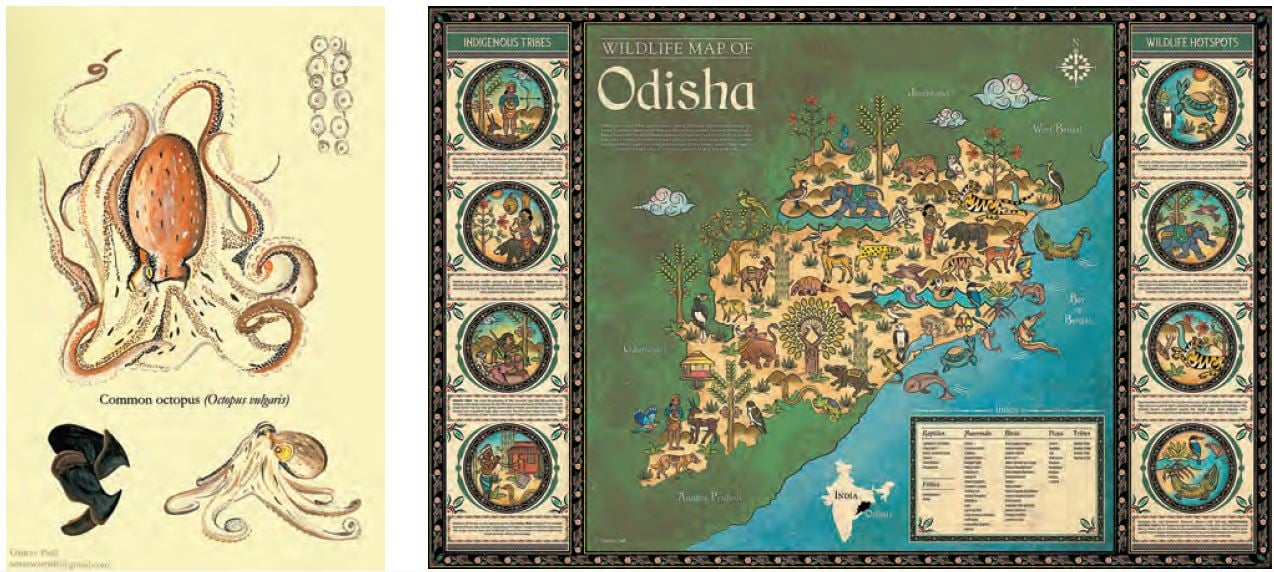

(Left) Marine biologist Gaurav Patil illustrates sea creatures; (right) Sudarshan Shaw has represented the flora, fauna and tribal heritage of Odisha

(Left) Marine biologist Gaurav Patil illustrates sea creatures; (right) Sudarshan Shaw has represented the flora, fauna and tribal heritage of OdishaZachariah began by participating in the ‘36 Days of Type’ project on Instagram, started by two graphic designers from Barcelona. She interpreted the 26 letters of the English alphabet and the numbers zero to nine by illustrating 36 endangered species, listing simple facts about them and the threats they face. She followed it up with another, dedicated to wildlife warriors—scientists, conservationists, photographers and others. These projects were noticed by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and she was invited to be part of WWF Voices, a group of professionals from diverse fields brought together to spread awareness about environmental issues.

Shocked by people’s ignorance and lack of concern for nature, Gogoi took to illustrating stories from the forests of northeast India. Under the moniker of ‘Wildscapes’, he creates illustrations and comic strips that turn the spotlight on issues in a light-hearted manner. Leveraging social media, Gogoi aims to create awareness about controversial projects sanctioned in the region. His most recent #IamDehingPatkai, was a campaign about the destruction of the Dehing Patkai rainforest by the coal mafia.

When marine biologist Patil was writing an article about his diving experience at Netrani Island off the coast of Karnataka, he realised that he didn’t have underwater photos to use with his article, and decided to use illustrations of the sea creatures. “From the boat, all you can see is the fin of an animal. Drawing an entire animal brings to light how small humans are when compared to some of these marine mammals,” he adds. There has been no looking back since, with Patil illustrating the logo and field guide for Marine Life of Mumbai, a collective that works to raise awareness about marine life, and is working with Wildlife Institute of India, WWF India and The Mangrove Foundation.

“Music, dance and art are intrinsic to human nature. We connect with them at a primal level,” says Shaw. Surrounded by rock carvings, tribal communities and wildlife while growing up in Bhubaneswar, his aesthetic is deeply shaped by these influences. He channelled these into a wildlife map of Odisha, a self-funded project that brought him recognition. Done in the Pattachitra style of painting, the map is a folk representation of the state’s rich flora, fauna and tribal heritage. His strength lies in interpreting traditional folk art in a contemporary manner. Next on the cards are wildlife maps of West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh.

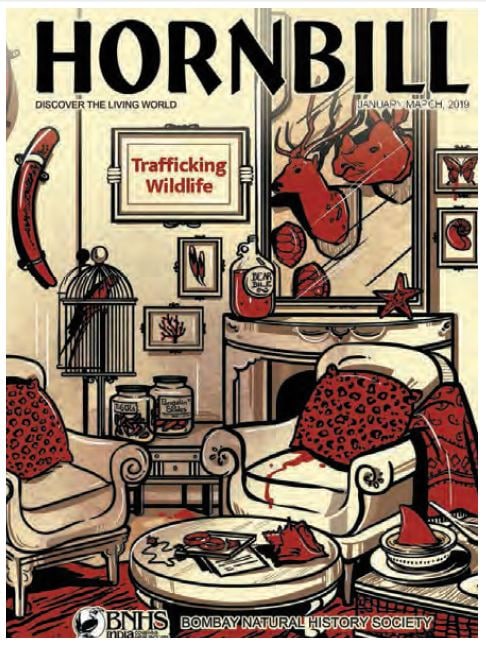

Designer Ashvini Menon is a consultant on the Hornbill magazine of the Bombay Natural History Society

Designer Ashvini Menon is a consultant on the Hornbill magazine of the Bombay Natural History SocietyMenon started with the Bombay Natural History Society, where she is a consultant on their Hornbill magazine. From painting murals in public spaces to conducting workshops, she tries to keep the focus on flora and fauna relevant to local regions. “I understand the urban audience better, and hence my work is focussed on them. I hope to encourage people to make small changes, and dissolve the line between environmentalists and people who don’t care about nature. I think everyone cares about nature, it’s just that they don’t know it.”

Both art and humour work particularly well with children, who form a considerable part of these artists’ followers.

Chakravarty remembers interacting with local children at the Hornbill Festival held in Pakke Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh. Poring over a map he had created, the children felt a sense of ownership and pride in their region and its rich biodiversity. His maps of Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh are regularly used by forest officials to educate local children about wildlife found there.

“I can’t make a cartoon and expect it to fix anything. Bringing about behavioural change takes a long time, but helping people build a perspective is important and possibly the first step,” says Menon. Her ‘Ecotism’ column in The Hindu was well received and many young children wrote to her saying they were inspired to protect the environment.

But cartoons too can have an impact. A reader from Peru wrote to Chakravarty saying how he changed his mind about buying a marmoset monkey after reading Chakravarty’s cartoon strip about the illegal monkey trade in the Amazon basin.

Chakravarty uses his voice to raise awareness about issues within India as well. For instance, when the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change proposed a draft Environmental Impact Assessment 2020 notification, he came up with comic strips to highlight the problems with the proposal. A visual summary of these were then used widely by lawyers, journalists and others to counter the proposed draft.

But speaking up comes with its share of challenges. “The instances when I am asked to tone down my messages has certainly increased in frequency,” he adds.

Shaw was questioned for showing tribal communities in his wildlife map of Odisha, and connoting that they are wild. The problem, he says, lies in how urban people view wildlife. “The definition of wildlife for indigenous people is different from those who live in urban areas. Indigenous people do not look at nature and wildlife as resources, as something different from themselves. It’s important to look at wildlife with our senses as fellow beings. If we do so, understanding them and living in harmony as beings who we share space with, will be easier,” he says.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)